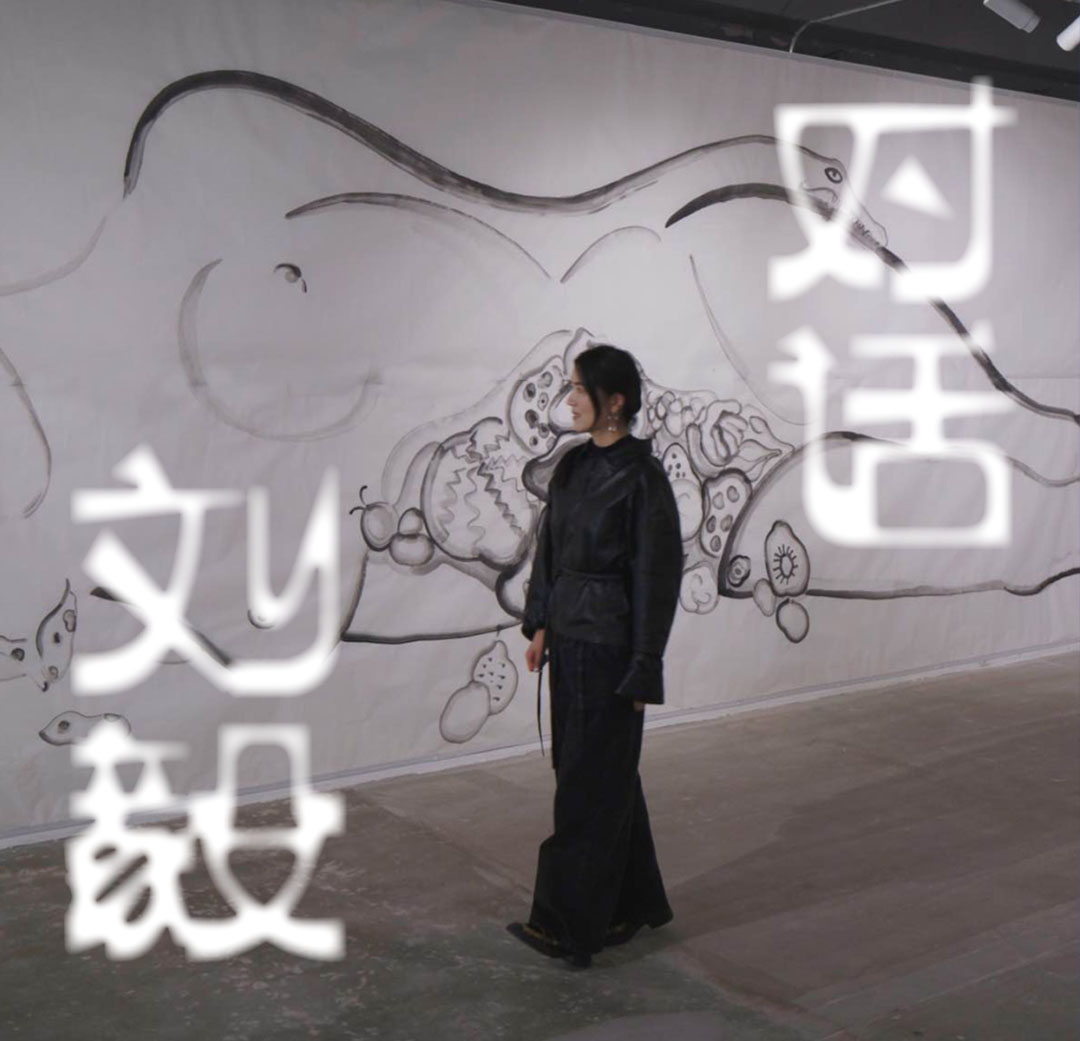

For Liu Yi, ink painting is not a languid form of lyrical expression. Her initial intent, beyond mastering the fundamental “childhood training” (tongzi gong) of traditional ink, was to exploit its inherent “speed”. The fluidity of emotion-laden brushstrokes, under the pressure of time, allows her to convey spirit and weave dreams into frames, crafting layered yet open-ended spatial narratives. Her swift, wet sketches and breath-like blank spaces deliberately invite interventions from installations and digital media...As one of the most compelling representatives of post-1990s ink animation artists, Liu Yi has come increasingly into her own. As she herself states in a voice both tender and resolute: “I want to create a nonlinear space—an indescribable, indefinable domain.”

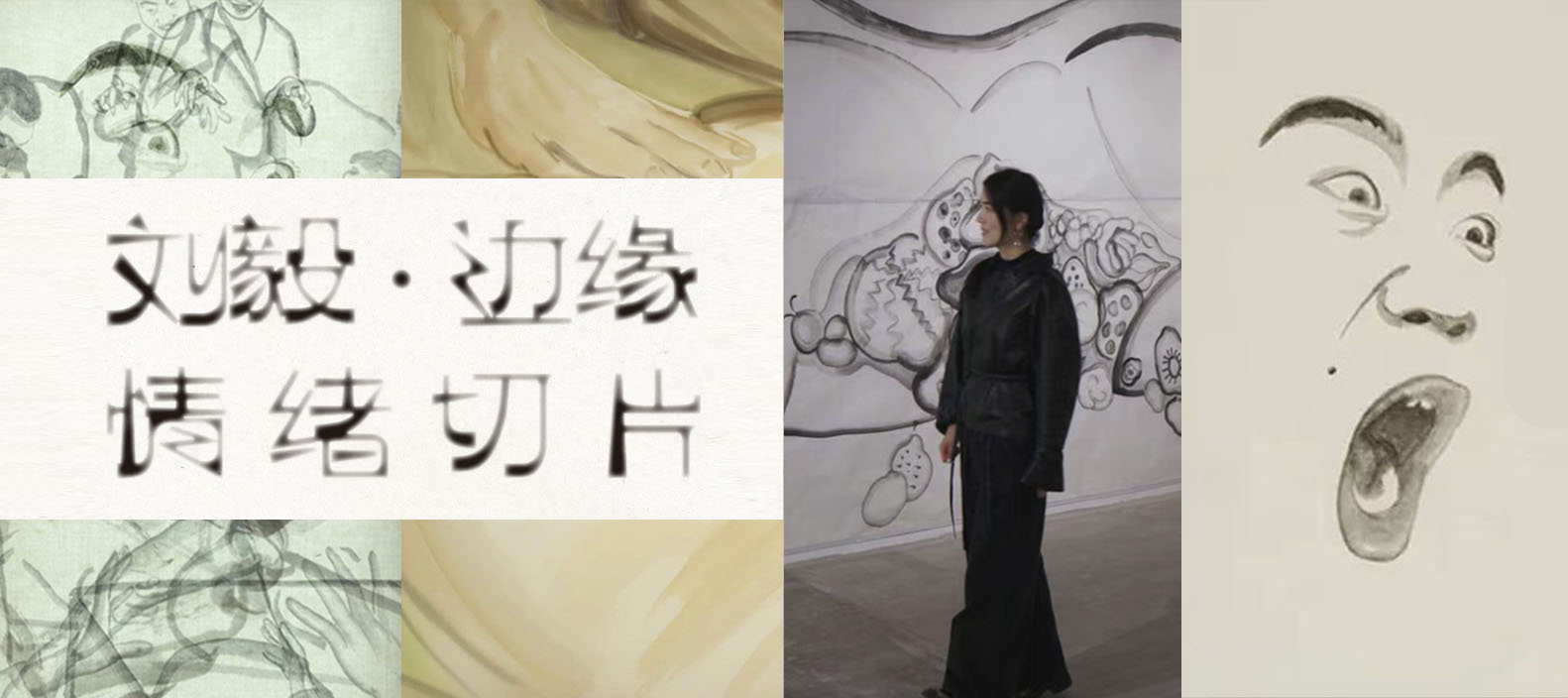

ShanghART WB Central recently presented Liu Yi’s solo exhibition "Diffusion Layer," the first comprehensive showcase of her six major ink animation works from the past decade: from her 2013 debut "Origin of Species" to "Nice to Meet You" (2024), commissioned by Ichihara Lakeside Museum Japan, and the ongoing long-form piece "Morning and Dusk, and No More" (2019), created during a residency in Cyprus.

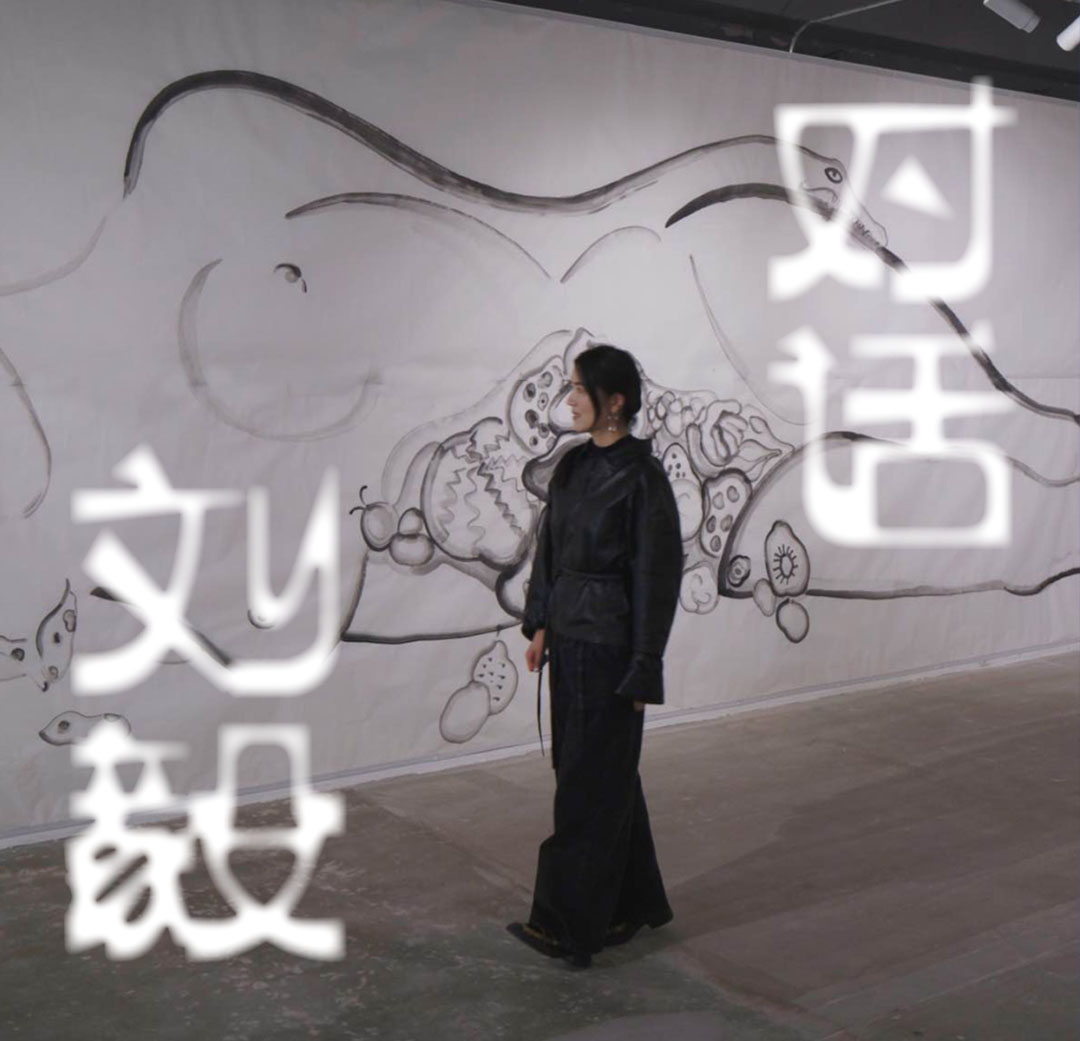

It is well known that European painting long adhered to frames and perspective, while classical Chinese landscape painting embraced a radically different composition. The latter transcends the confines of walls, it embodying momentum in tranquility, thus becoming a spatial extension. Liu Yi is captivated by this boundless fluidity of time and space. Whether on rice paper, silk, lightboxes, or digital screens, her imagery, rendered with masterful ink strokes, achieves an "emotional sketch"—a "gushing translation" of realist states.

Imagine a woman from Jiangnan, wielding water-like brushstrokes to slice reality, storing sequences of everyday life from marginalized communities in fragmented layers.

Born in Ningbo, Zhejiang in 1990, Liu Yi graduated with a master’s degree from the China Academy of Art in 2016, where she studied in Yang Fudong’s “Experimental Video Studio.” By integrating various media such as ink painting, animation, video installations and drawing, she explored the multi-dimensional ways of human existence, particularly focusing on marginalized individuals and ethnic groups.

Since the Tang Dynasty, Chinese landscape painting has embodied "images beyond images" (象外之象),merging time into space to guide both creator and viewer on a mental journey, evoking life’s vicissitudes and offering spiritual solace or catharsis.

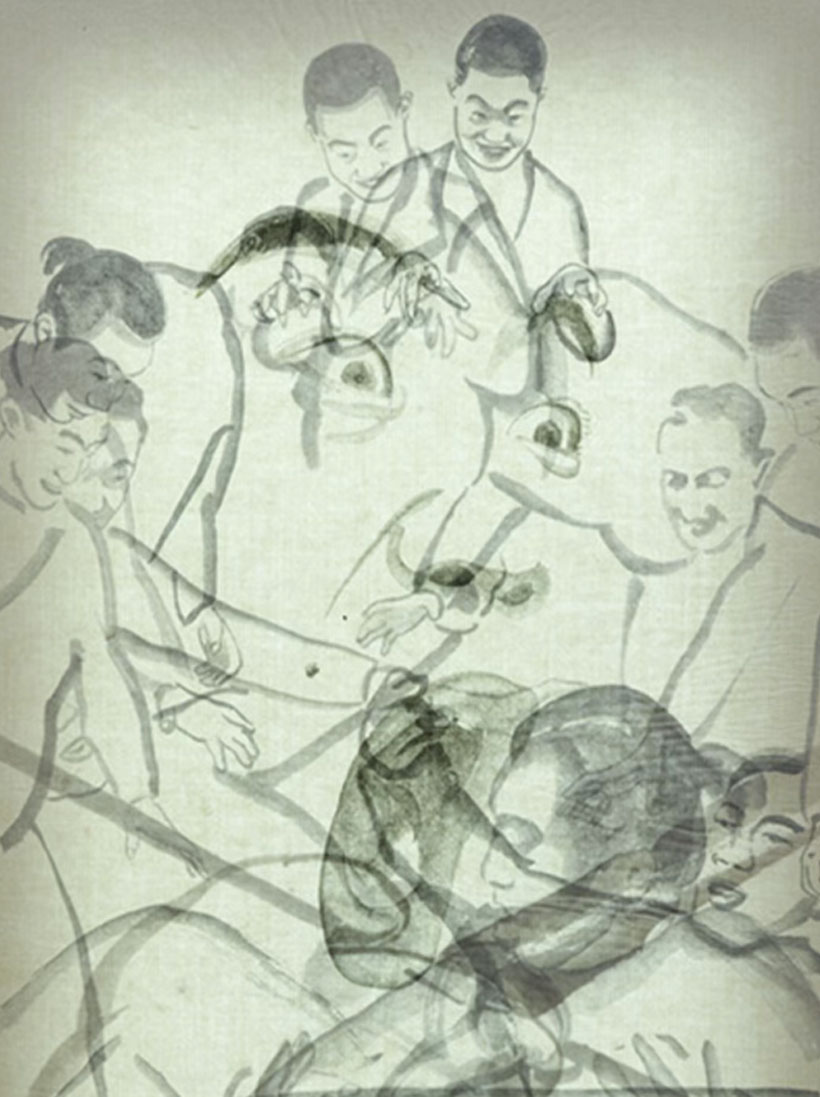

In “The Earthly Men”, the focus is on the ‘DAN MIN’- the people who live on boats in the southeastern coastal areas of China. These people, without stable land, surnames, or recognized ethnicity, remain largely unseen. One can imagine the artist standing by the shore, gazing across water veiled in mist, mountains faintly visible beyond, yet her vision extends further than pastoral tropes. A man’s face, blurred into obscurity with only his terrified features remaining, pierces through the disorientation of both reality and psyche. In a few strokes, Liu delineates the drifting condition of humanity—those caught as floating debris, exiles, or border figures.

In "Morning and Dusk, and No More," hands knead dough for bread over and over, living "no more" days that require no intervention yet admit no change—love and warmth persisting in limbo, forever diffusing.

Her work traverses tradition and contemporaneity,reaching toward a new visual lexicon. Like meditation, it lets emotions flow freely in emptiness, embracing the inexhaustible and unfillable.

"The loneliness and detachment ink brings—its elusiveness—is not about direct narration but whispers. That sense of alienation isn’t pain; it’s more ethereal." This is precisely what Liu Yi seeks.

Today, her films and installations are exhibited globally at institutions like Tate Modern, Seoul Museum of Art, Power Station of Art (Shanghai), Ichihara Lakeside Museum (Japan), and Art Basel Switzerland. "When I Fall Asleep, My Dream Comes” won Best Animation Award in the Short Film Unit at the Shanghai International Film Festival. "The Earthly Men" was awarded the UOB Art in Ink Awards(Emerging Artist Award).

In recent years, she has been invited to residencies and commissions across Asia and Europe. Her works have been acquired by major collections including White Rabbit Gallery (Sydney), Stanford University East Asia Library, M+ Museum (Hong Kong), and the Power Station of Art (Shanghai).

"Diffusion Layer" originally refers to a physicochemical phenomenon where substances gradually expand, blend, and blur in space.

When the "diffusion layer" becomes the showcase of this decade's artistic journey, it transforms into a multi-dimensional metaphor, confirming Liu Yi's astute and unconventional growth.

The misty flow unique to ink is diffusion; memory’s passage through time is diffusion; the fusion of traditional ink and AI technology is a meticulously orchestrated yet serendipitous diffusion.

How did your artistic journey begin?

At the Affiliated High School to China Academy of Art, I completed foundational art training. In 2009, I entered the academy’s New Media Department. Initially, I didn’t explore animation until studying under Yang Fudong and joining his "Experimental Video Studio," which connected me to video art.

For one of the courses, we were required to complete 800+ storyboard sketches for "Infernal Affairs" within a few days. Instead of using the conventional A4 grid drawing method, I bought several thick blank notebooks, worked horizontally, and chose to use ink materials. In my opinion, ink is extremely efficient in handling form changes and the relationship between light and shade. The fluidity of the ink also precisely mimics the changes of light sources and the layers of space - whether it's a close-up or a distant view, it can naturally be depicted.

Which ink painters influenced your animation style?

I gravitate toward emotionally charged literati painters such as Fu Baoshi and Xu Wei—whose brushwork embodies tempestuous energy. From the fierce storms and rain, to the unrestrained depiction of flowers and birds, to the struggle of life. Especially Xu Wei - his broken, explosive strokes resonate with raw emotion, a burst of ink splashing across paper, I can feel that he is depicting his current state, with splashes and splashes of ink. Some parts are soft, but in fact, the energy of that emotion is very strong.

Growing up in Ningbo, how did your childhood environment shape your vision?

The rhythm of the sea and the tides, it has a breathing pattern and constantly changes. It is a floating, vague, and uncertain state. Sometimes it is hidden in the fog, and sometimes it is illuminated by the sunlight. On the sea surface, there appear colorful light spots like diamonds, which are a kind of image memory. Subtly... My works contain water and waves. My hometown of Xiangshan’s low-lying mountains, half-veiled in mist, and winding coastal roads cultivated my fascination with nonlinear space, a sensibility that permeates my work.

"The Earthly Men" reminds me of a set of paintings by Zhou Chen from the Ming Dynasty, titled "Beggars and Street Characters“ (流民图). The main characters in these paintings are common people, including beggars. Through exaggerated and humorous depictions of their clothing and behaviors, it aims to "warn the public" or "enjoy life together with the people". The theme of "The Earthly Men" comes from people living and working by the water. I noticed the terrifying and exaggerated expressions of those characters.

The ‘DIAN MIN’ who have been marginalized by the times have wandering eyes. I removed many facial details and only kept the facial features, concentrating emotions, or it can be regarded as a "deformed mask". He is no longer a specific individual. It might be a kind of whisper and rebellion against the mocking statement "the leftover elements of society". Sometimes people use exaggerated expressions as a magnifying glass for their external emotions.

Unlike idyllic village scenes in Chinese ink,such as “Village Children Frolicking in School”,”In a Melon Patch or Under a Plum Tree”, what is your main focus?

The themes you mentioned represent an idealized rural daily life, a stable, harmonious world that is imbued with ethical order and the aesthetic of harmony between man and nature. What I am more concerned about, however, are the people and moments beyond those orders.

The mobile individuals, the marginal situations, and the emotional fabric of people in unstable environments. For instance, in "The Earthly Men" and "Nice to Meet You", they are questioning: "In a disordered social structure, how can people find a place for themselves within their own bodies?"

Who is the man in "Burning"? In ink painting, water is depicted as natural. However, there aren't many depictions of fire. Why do you create such a dilemma?

An abstract image of a man. I think he has a strong sense of power. Water and fire actually have something in common - they are both extremely uncontrollable existences. Have you noticed that when fire loses its color, it turns into water...

During your residency in Cyprus, you created the animated film Morning and Dusk, and No More. It resembles the work of a journalist or documentary filmmaker, capturing the lives and circumstances of local people.

I entered Salamiou village as an outsider, observing daily lives without imposing. I didn’t understand their language. I was more like a friend from afar, unassuming and non-intrusive. When I picked up the camera to record, people were less guarded.

The protagonist of the film, Vrionis, is one of the few young people left in the village. Like many remote towns in China, the younger generation leaves to seek work elsewhere, leaving behind the elderly and marginalized groups. Vrionis and his mother care for his intellectually disabled sister day after day. I wasn’t trying to make a grand statement; I simply recorded life as it unfolded: conversations in coffee shops, kneading dough at home. What’s interesting is that only later, after returning home and slowly organizing the footage with the help of a translator, did I learn about the subtle affections that had quietly developed between the man and others in their daily interactions. That delayed realization, blurred by time and distance, carried its own hazy poignancy.

Are you more intrigued by cultural differences or human commonalities?

Commonalities. Just like what I experienced in Cyprus, when I was in Hangzhou, I often participated as a volunteer in activities to care for children with autism, playing basketball and engaging in other interactions with them. The problems faced by these children's families are similar to what I experienced in Cyprus. You can imagine that in most cases, it is women who take on the role of family care. Originally, she might have had a good job and career plan, but now they have to... "Love" often contains many "musts". In the group exhibition held at Nanjing Golden Eagle Contemporary Art Centre, we also discussed the difficult topic of love.

For artists, how to depict this "musts"?

The German philosopher Schopenhauer's porcupine dilemma describes how a group of porcupine, in the cold winter, want to keep each other warm and get close to each other. However, getting too close would cause their spines to hurt each other. This theory illustrates the game in intimate relationships. I have kept hedgehogs before, and during the winter, they would do the same to keep warm. This time in the exhibition hall, I made a "hedgehog sofa", which looks very painful, but it also has very soft parts. For example: "I really want to like you". This is actually a very brief moment that fleets. Because taking a step forward means love, and taking a step backward means no. It is a game between rationality and emotion.

Does the understanding of emotions stem from personal experiences?

It is not a direct reflection of a specific romantic relationship or family memory. Rather, it is more like a subtle resonance that occurs after a long-term coexistence between the body and emotions. However, what I often focus on are those "unexplainable" parts: the weariness and tenderness accumulated during long-term care, the guilt that cannot be expressed when parting ways, the elusive sense of closeness that cannot be reached, and the subtle estrangement that arises from long-term coexistence. They seep into the body silently and slowly like water, yet are extremely difficult to precisely capture in words.

"Morning and Dusk, and No More" retains traces of AI collaboration.

Yes, it is a derivative of the "carefully crafted series of unknown errors", which I call "digital ghosts", emerging from the gaps of this series. The process of working with AI is like taming a wild horse. It often gets out of control, but I quite enjoy this evolution. I don't use the images generated by it to create paintings as my own paintings. Instead, I want to show the thinking process of it. At the same time, the images it generates often exceed my expectations. Even though it cannot understand my instructions, it has its own thinking. It must generate an image to fill the void left by the instruction.

“Diffusion Layer” showcases six major works from the past decade. What emotions does each carry? Looking back, which one was the most challenging to create?

“Origin of Species” was my first attempt at animation,a study of motion trajectories and ink control. It captured that tension between control and chaos, much like emotions themselves. “Burning” marked my earliest collaboration with AI scientist Zhang Rui, using AI to assist the creative process... only to discover it wasn’t quite so "obedient"!

But later, it was precisely that uncontrollable fluidity and the nature of fire that matched so perfectly. Because fire cannot be shaped by any object and is impossible to replicate. Each creation is an experiment. It is not a linear process; it's more like a series of "slices". Although it spans ten years, it feels like the same body's undulating breath at different times. There are sharp parts, as well as warm and flowing elements.

Your works are very likely to trigger dreams.

Dreams are originally a kind of "image structure" stripped of logic. "Falling", "lying flat" and "repeating" are subconscious narrative methods. Ink wash itself is suitable for expressing such flowing and non-linear emotions. Slow, broken, fragmented, and suddenly leaping.

I have a work titled "When I Fall Asleep, My Dream Comes". I'm wondering why we dream, if it has some function, or if dreams are a passage into a parallel universe, an experience of another self in that parallel universe...

Can artists control emotional diffusion?

It’s a kind of semi-controllable and semi-uncontrollable state. We may be able to control the rhythm of the scene, the arrangement of the images, and the boundaries of the technology, but the true flow of emotions is often beyond our control. We should strive to create a structure that allows emotions to grow, overlap and flow naturally.

Do you think the fluid is time, the environment or human survival?

All of them. Our emotions are drifting, and the memories and language we rely on are gradually losing weight.

It is both individual and collective. Sometimes we see a person walking very slowly, as if they were still in the same place, but at the other end they return to the starting point. It seems that I am trying to find a coordinate in this flow.

What is your thought sequence when considering plot, composition, and color? As someone who simultaneously plays the roles of director, screenwriter, and art designer, does your exploration of ink animation feel like a process of deconstruction or an added burden?

First, I determine the style and select the appropriate paper, then move on to the narrative elements. The most time-consuming and demanding part is actually the animation process. Finally comes scanning, animating, and adding music. The volume of frame-by-frame hand-drawn sketches is enormous - dozens of completed drawings might be spread across the floor drying. At this point, I contemplate how ink in its dry state differs from when it's wet. Most ink paintings we see are dry, but the most beautiful state is actually that semi-dry, still-damp quality. I wonder: can I preserve this transitional state? So I capture and scan the images while they're still wet. That's why in the final animation we see ink imagery brimming with moisture - frozen in that precise moment. It carries both the misty atmosphere of dreams and a slightly sorrowful emotional quality, like tears welling up but not yet fallen.

Your soundtracks are remarkable.

I think music is another form of "emotional ink". For "Morning and Dusk, and No More”,I invited a band from Cyprus named Antonis Antoniou. I made a trailer to describe the feeling, and I said I would use the Cypriot Sitar. Later, it was quickly produced. When I listened to it, wow, it was exactly that feeling. For "Burning", the composer was Zhang Xin, and the sound engineer was Li Lefu. They have both talent and an experimental spirit. For example, they placed many marbles on a plate to simulate the sounds of nature.

How has your working methodology evolved over the past decade?

Each work takes us one step forward. "The Mushroom at the End of the World" (by anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing) is a book that delves into the fieldwork and philosophical concepts of the rare fungus called the mushroom. This book has influenced many artists, especially those who create works related to the theme of mushrooms. They had previously seen my works and commissioned me to create an animated short film. Working with anthropologists and scientists for the first time was very new to me, as artists often tend to get stuck in a "self-referential" state. This collaboration gave me a solid foundation for theoretical research. It will be exhibited in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, in November this year.

The French art critic, Hippolyte Taine, who wrote The Philosophy of Art, once said: No matter how broad your mind and heart are, they should be filled with the thoughts and emotions of the times. What are your "contemporary thoughts and emotions"?

I think it's a sense of powerlessness in the midst of data expansion. During the transitional period of the times, there is a disorientation in the positioning of identities in the global movement. Of course, my works are not aimed at solving problems, but at creating a space where people can feel the existence of these problems.

Current reading preferences?

Mythological and science fiction novels. I really like Ted Chiang's "Story of Your Life", "Arrival" and "Exhalation". They are fictional, yet seem to be real.

What was the most important lesson you learned from Teacher Yang Fudong during your student days?

He has always advocated "independent thinking, nothing new can be established without breaking through."

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Editor:Tiffany Liu

Designer:Yizhou Shen

Image provided by: Artist Liu Yi, ShanghART, and Oui Art