Liu Cong takes some pleasure in hearing others describe his paintings as resembling the person himself. Even though, in his practice, he deliberately avoids storytelling, he confines subjectivity within a narrowly defined range. For Liu Cong, painting as a mode of expression is not merely a way of “describing” the world. Rather, it should possess a capacity parallel to—or even surpassing—that of language, enabling a direct and unmediated encounter with the world, while at the same time confronting the self honestly within it. In this process, the artist does not always stand ahead of the viewer; he may even diffuse and disappear, much like Roland Barthes’s notion of “The Death of the Author.”

In 2018, Liu Cong offered a self-reflection on his practice, describing its scope as “an abstract form of expression that takes as its foundation the contour of objects existing in space as structural and linguistic signs, together with the embodied reality that emerges upon the pictorial surface in the process, drawn by the gaze and responding to inner sensibility.” Five years later, when I presented this statement to him as a kind of footnote or corroboration of his work, he found it unfamiliar, though he admitted that certain key terms still resonate within his current framework of thought. This past March, ShanghART Beijing hosted Liu Cong’s first solo exhibition, The Long Now. In this exhibition, one could discern the continuity of his long-standing line of inquiry. At times, it is the work itself that more readily attests to its own coherence than the artist; for any artist wishing to establish a personal mode of creation and expression must first confront and overcome the formidable traditions embedded within technique or medium—since every act of making is inevitably bound to concrete materials.

Liu Cong is acutely aware of the singularity of painting, as well as the limitations language encounters when it seeks to approach painting. Thus he has never been able to truly “speak” it to me. He prefers painting to remain painting itself—neither instrumental nor intervening—its center forever preserved in a state beyond articulation, so long as it shines with sufficient radiance to illuminate all things: whether what lies before us is a thicket of darkness and impenetrable brambles, a broad and level clearing within the forest, or merely a winding garden path that leads into seclusion, without ever forking away.

POINT TALK 01: On “What Kind of Work Painting Is”

This was the first question I posed to Liu Cong, and it lay at the heart of our conversation. At its core, it is an immensely expansive question, encompassing both the artist’s conscious approach to expression and their insight into the self, the interplay between self and others, and the relationship with the world. Throughout our two-hour dialogue, every question and answer continually circled back to this central point.

OUIART:Could you share the origin or starting point of your engagement with painting? Among the many art forms, why did you choose painting in particular? And for you, what kind of work is painting?

Liu Cong:Of course, it began with sheer affection. What allowed it to endure were countless coincidences: a persistent desire to paint, questions that were never fully clear, and, in the act of painting, continual new insights and ideas emerged—so the practice carried on. Compared with other media, painting is relatively simple and direct in its operation; one can maintain full control. Yet, once one comes to understand and accept its limitations, its side of boundless possibility opens up to the painter—a truly fascinating experience.

POINT TALK 02: On “Handling a Painting”

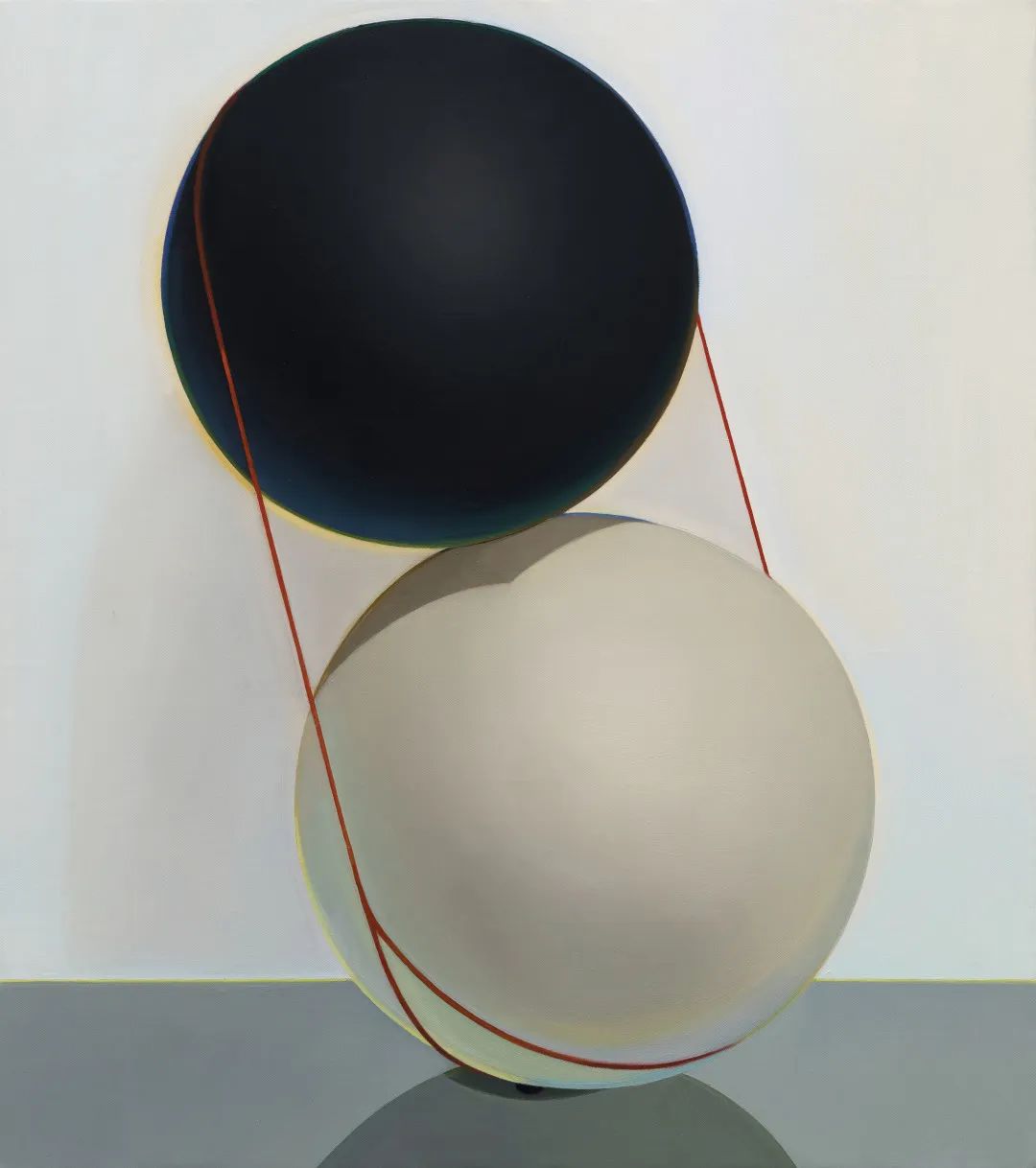

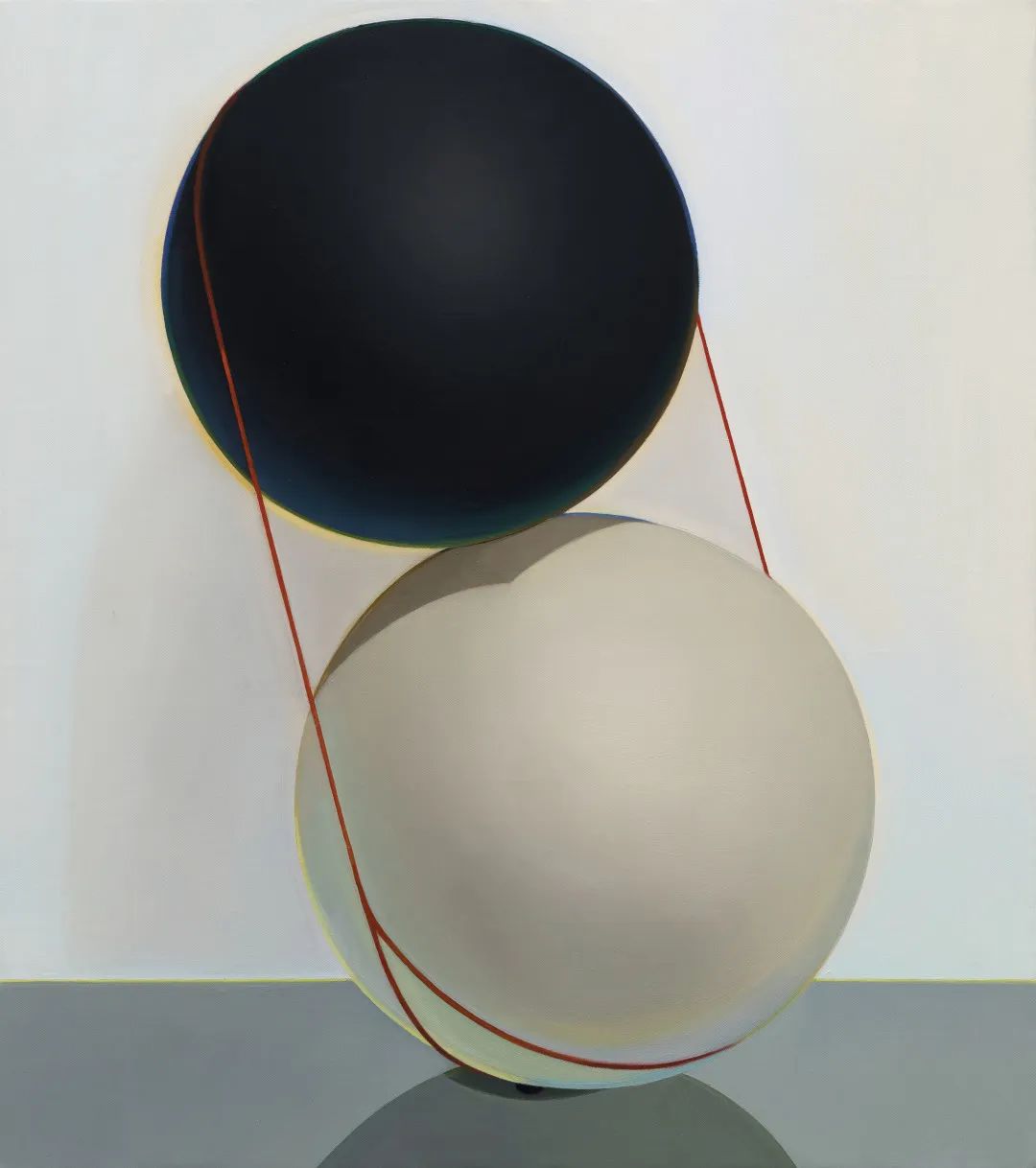

In his painting, Liu Cong is both highly perceptive and deeply faithful to himself. In his early works, one can readily discern the influence of photography and cinema. Yet he soon turned toward “symbols,” incorporating everyday objects—umbrellas, paintbrushes, candles, pot lids, books, bones—each imbued with his singular temperament. At the same time, he does not shy away from repetition, for repetition is also a part of life. At times, the degree to which he revisits a single object approaches a form of “practice,” much like a poet refining words or a musician tuning an instrument.

OUIART:In the exhibition The Long Now, we encountered a series of your new works. Among them, you have painted numerous “sheets of paper,” whose spatial contours appear more complex than the forms generated by the everyday objects you often employ—such as “balloons,” “mirrors,” “paint rollers,” or “paper cups.” Could you briefly share what you aimed to engage with in creating the “Paper” series?

Liu Cong:First and foremost, I am always working with the painting before me; this is the sole focus I confront in the process. Regarding the composition itself, I strive for the expressive order of the painting to be as clear and precise as possible—the rational framework is established from the outset, providing what one might call a sense of direction. Yet the progression and completion of the work are always measured by immediate, sensory experience. For this exhibition in particular, I wished for the exhibition itself to function as a complete work, where the space and the artworks share a relationship of structural language. This includes the dimensions of the walls, the spatial architecture, and the treatment of wall colors—all of which resonate perceptually with the content and form of the works. For me, this logic aligns with the approach I take toward the painting itself; the difference lies only in that the flat and the three-dimensional represent two dimensions of space.

OUIART:From my perspective, another notable feature of the new works in this exhibition is that you place these everyday objects within a very confined space, creating an intense focus. Why did you choose to do this? At the same time, I am also curious: what lies beyond the edges of your frame or viewpoint? How do you decide what to include or exclude?

Liu Cong:I placed a text in the exhibition space, which reads: “I extract objects from the experiential world they inhabit, cleansing them of the myriad meanings attached to their surfaces, and present them to my gaze in a relatively bare state. This grants me a degree of freedom in approaching art, making direct, intuitive experience possible.”

I am drawn to confrontation, to a language laid bare, and I also wish for all perceptible content of the work to be presented equally on the surface.

Beyond the viewpoint lies an infinite diversity; human vision is always limited. The forms established within the frame, for me, serve as the structural scaffolding of the composition, a vessel for containing color.

POINT TALK 03: On “Structure” and “Imagination”

During my conversations with Liu Cong, I could not help but recall Calvino’s crystalline writing and Auden’s conception of poetry as a game of knowledge. In both literary frameworks, creation is regarded as a precise system—governed by rigorous order, yet endowed with expansive interpretive possibilities and intricate weaving—so that within a finite form, one can refract infinite, intellectually rich content, while also revealing the delicate balance that expression seeks between absolute freedom and self-imposed constraint.

OUIART:For a period, you used photographs as a basis for your painting, but later abandoned this approach. Why?

Liu Cong:Painting with the aid of photographs is hardly a novel practice—different painters employ photographs in various ways, and art history offers abundant discussion and experimentation on the relationship between painting and photography. For a time, I was particularly interested in Richter, as well as the Belgian artists Luc Tuymans and Michaël Borremans, and of course David Hockney. Their painting practices all engage with photographic or image-based sources. Yet the more I studied and appreciated their work, the more I felt the absence of a perspective that was truly my own, and so I had to seek another path.

OUIART:Your work deliberately eschews “narrativity” and “imagination” in favor of “structure” and “form.” (Is this related to your effort to strip away the influence of photography or photographs in your practice?) Yet for a creator, the former often seems more readily associated with so-called “creativity” and “subjectivity.” How do you approach the concepts of “narrativity,” “imagination,” “structure,” and “form” in painting, and how do you understand their interrelations?

Liu Cong:It is somewhat related, but I think contemporary people can hardly “detach” themselves from the influence of photography and photographs on vision. As Heidegger once observed, they profoundly shape our perceptual experience and even the way we comprehend the world we inhabit.

Today, we live immersed in an omnipresent flow of images. Many outstanding photographers and visual artists are equally creative subjects, and in fact, some handle images in ways that are even more painterly than painters themselves. I believe distinctions based on medium are not crucial; visual language exists equally across media. Yet differing surface textures and formal languages inevitably give rise to distinct modes of reading and perception.

Narrativity in painting is a vast topic, and in fact, it is even a technical matter within the medium. Simply put, in my understanding, narrativity and imagination constitute a structural relationship, encompassing what the viewer generates when engaging with the structure of an artwork. It is not an external concept imposed from outside.

OUIART:Does the weakening of “narrativity” and “imagination,” and the turn toward a more measured, rational mode of expression, constitute a resistance to the proliferation and misuse of images and imaging technologies, or is it a response to the very predicaments that painting itself faces in our time?

Liu Cong:I’m not quite sure how you understand “narrativity” and “imagination.” Typically, people associate imagination with Romantic or Symbolist connotations. In my view, however, imagination possesses structural qualities: it establishes connections between seemingly unrelated things. These connections impart a wholly new sensation to the linked objects, activating them within a new context and even evoking a sense of rebirth.

I do not consider myself to be weakening imagination. More precisely, I maintain a certain resistance to the projection of the “self” within images, and adopt a cautious stance toward an overreliance on literary qualities in visual art. Painting has its own language, and a pronounced material presence; its very existence is, in itself, a form.

It seems that painting faces no real predicament—or perhaps only the hypothetical assumption of one. Some have used this assumption as a basis for ontological reflection. Yet if you are willing to entertain it, entirely different hypotheses and judgments can be made. It is not about resistance; it all stems from genuine interest.

POINT TALK 04: On “The Openness of Expression”

Art does not imitate the visible; it seeks to bring the invisible into being. This, perhaps, is the ambition of every creator. The “father of modern art,” Cézanne, distilled this pursuit in the phrase Penetrate the object. Yet, as Julian Barnes has questioned: as the visual arts continue and art itself evolves, might the transition in painting from figuration to abstraction—and the subsequent ripple into broader cultural realms of conceptually charged, open expression—at some point degenerate into a pitiable error?

OUIART:By depicting everyday objects through a process of abstraction and extraction, do you risk excluding the richer, more complex information and experiences of life? Could it be that, at the level of expression, the artist constructs only an illusory openness?

Liu Cong:First, I am not depicting everyday objects per se, but rather using them as a means to realize the expression of the painting. What we see are the paintings themselves, not the objects. Everything that unfolds around the artwork responds to and enriches life’s experiences—this is the relationship at play.

Secondly, every mode of expression carries its own perspective, and within that perspective lies the inherent limitation of human perception. What we can do is remain conscious of these limitations—what might be called knowing that I do not know.

Openness is not correlated with the complexity of information. It is founded upon perception and imagination; the openness of a blank sheet may surpass that of an entire book. To me, openness is also a kind of structure: it is not merely the unidirectional output of the expressive subject, but also encompasses the perception and understanding of the receptive subject. Moreover, across different dimensions, there exists an openness of thought and feeling.

OUIART:Would you agree that, to some extent, painters or creators act as translators—seeking, through a series of self-imposed “procedures” or “methods,” to convey to others the world as we ourselves “see” it?

Liu Cong:Not a translator, but a creator. Art arises from nothing; painting is a making upon the flat surface. The first encounter with a painting is always a direct, sensuous intuition. “Comprehension” emerges only after this sensation, reshaped through rational reflection. To “see” is a precious state—indeed, in everyday life, we often remain blind to so much. The procedures or methods of creation can be understood as grammar: normal speech and conversation require logic, yet this does not imply that “expression” amounts to indoctrination or preaching.

Liu Cong’s structural reflections on creation have long been integrated with his everyday perceptual experience. Regarding intuitive and non-intuitive matters, he places greater emphasis on the individual’s freedom to shift perspectives, as well as the integrity of their dual aspects—much like his insistence that painting unites body and emotion, psyche and spirit. I hope that he remains in the stable state he seeks, continuously working to construct a chain of painting uniquely his own, each link testifying to and illuminating the others.

Interview, Writer:子七

Editor:Simone Chen

Designer:Nina

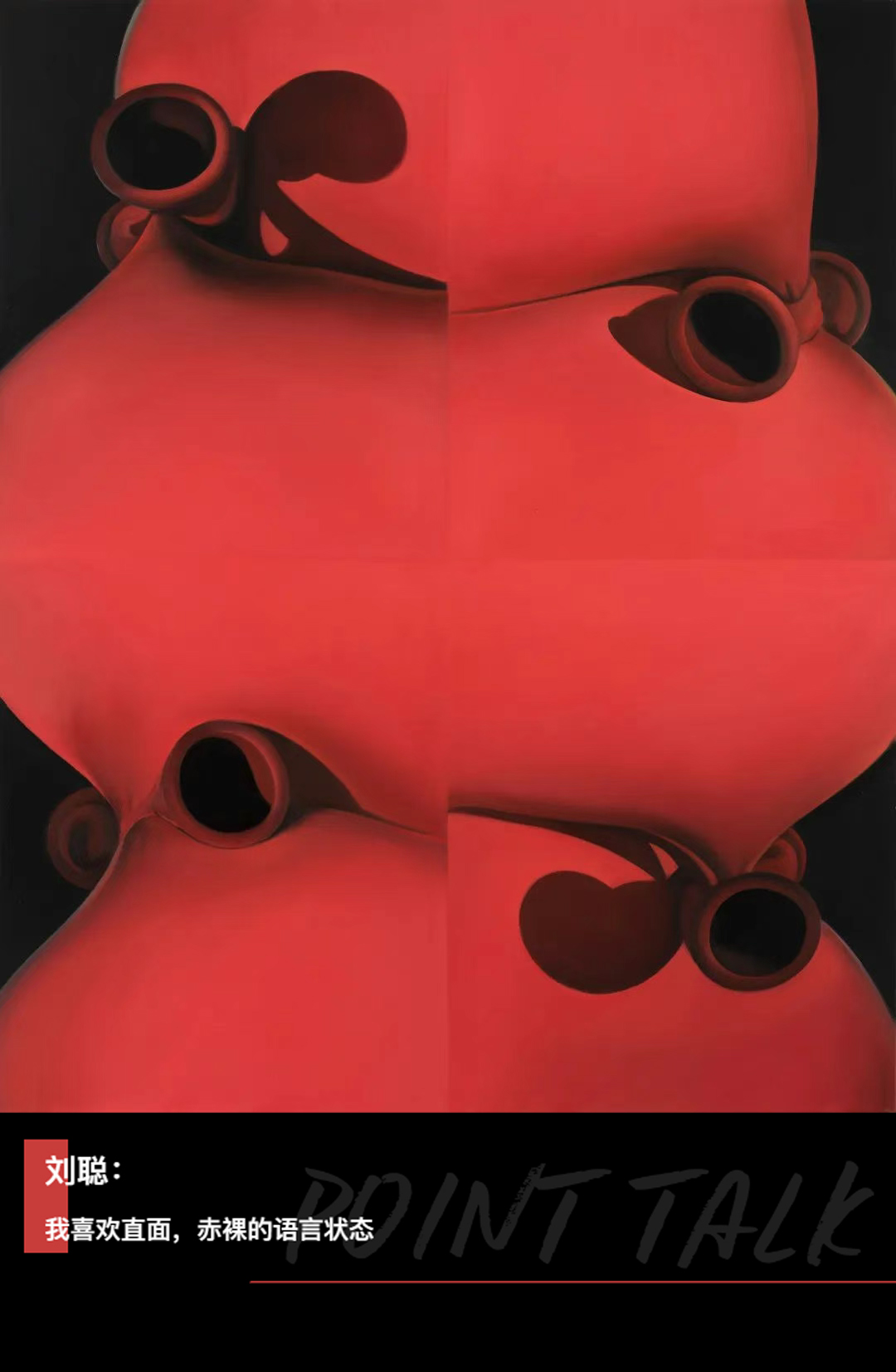

First picture: Liu Cong, Red Balloons - Four Grids,2022

Oil on canvas,190x153cm

Image provided by Shangh ART