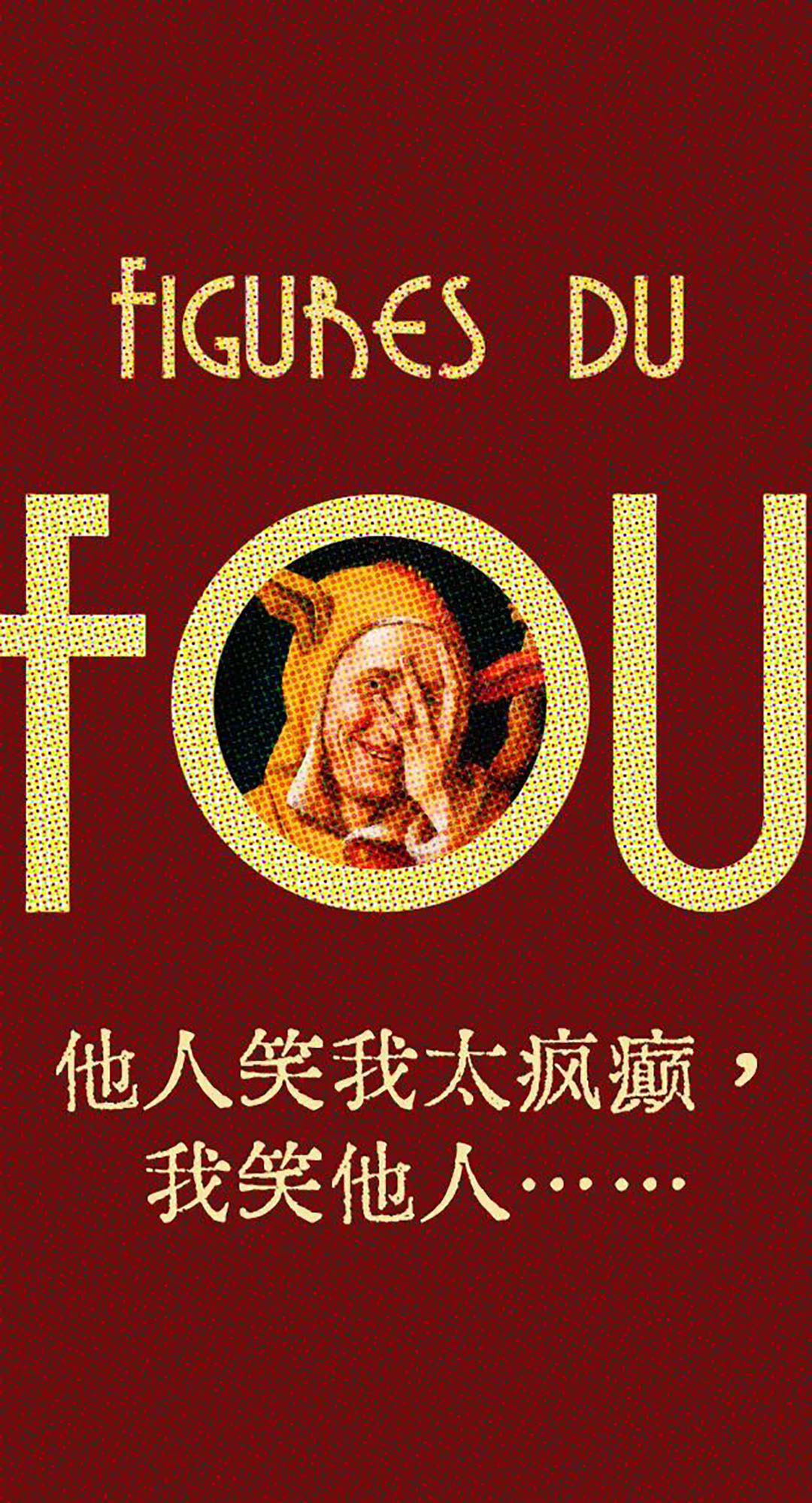

A fellow wears a yellow cap with donkey ears, grinning wide with slightly dirty teeth, one hand covering half his face, his eyes wide-set. This painting, created around 1537 by an anonymous Dutch artist, is titled Portrait of a Madman Peering Through His Fingers (Portrait de fou regardant à travers ses doigts). It serves as the promotional poster for the Louvre’s new exhibition.

The exhibition’s name first caught my attention—Figures du fou, du moyen âge aux romantiques ("Images of Folly: From the Middle Ages to Romanticism"). You could also call it "Portraits of Fools" or "Depictions of Madness"; in French, fou means both "mad" and "foolish"—often indistinguishable. I nearly skipped with excitement on my way there—over 350 paintings, sculptures, rare manuscripts, prints, everyday objects—and one big question in mind: how does the Louvre define “fou”?

1. "Take Out the Mad Stone", only Bosch

If you plan to visit Figures du fou, ensure your phone is connected. Behind each artwork and label lies a trove of information demanding quick searches or even ChatGPT consultations. Call it "50% viewing, 50% storytelling." Time is limited, but if there’s one "madness" not to miss, it’s Hieronymus Bosch.

In the Middle Ages, people believed madmen had a "stone of folly" lodged in their foreheads—extract it, and sanity would return. This is the scene Bosch depicts in The Cure of Folly, Extraction of the Stone of Madness.

"Doctor, please chisel out this stone in my head! My name is Lubbert Das." Golden script frames the painting. Lubbert Das, a recurring fool in Dutch literature, is often portrayed as obese and lazy. At the center, a pallid, rotund patient is strapped to a surgical chair, clad in red tights, wooden clogs neatly placed beneath. A surgeon in a funnel-shaped cap wields a scalpel; instead of a stone, he extracts a flower—a tulip. Another tulip lies on the table. In 16th-century Holland, tulips symbolized folly and madness!

A monk holding a wine jug lectures confidently, while a nun balancing a book on her head watches coldly. Under these authorities’ gaze, the absurd becomes rational. The horizon shows towns, villages, church spires, grazing sheep, farmers plowing, milkmaids—all bathed in infinite blue...

Back then, quack doctors roamed the countryside, their "stone-extraction" surgeries mere charades. Bosch frames the scene in a circle, like a peephole or magnifying glass.

This medieval painter, often hailed as a precursor to 20th-century surrealism, filled his works with madmen, fools, demons, hybrids, and cryptic symbols. Some view his art as lunatic visions; others see a heretical cipher.

Beyond textbook staples like Movimentos Artísticos, the Louvre exhibition showcases Ship of Fools, another masterpiece. Inspired by Sebastian Brant’s satirical epic, the painting depicts 111 fools en route to "Narragonia," a fools’ paradise. Each represents a folly—lustful clergy, drunken jesters, decadent nobles...

The ship has no rudder, sails, or functional oars. Its passengers carouse, oblivious to impending doom. Bosch remarked, "This is how humans live: eating, drinking, flirting, cheating, playing foolish games, chasing the unattainable."

Seeing it in person: At the center, a priest and lute-playing nun prepare to bite a wafer dangling from the mast. Cherries (symbolizing lust) litter the table. Below, two drowning men clutch the hull. Behind the nun, a figure wears a cup on his head; another raises a jug to strike a youth. To the right, a red-robed man wields a spoon instead of an oar. A drunkard vomits overboard, hugging a tree where a hunchbacked jester drinks.

Look closer: The jester steers. Bells adorn his outfit; he holds a "fool’s scepter" topped with a miniature head (the exhibit includes a boxwood Marotte—later inspiring perfume bottles with "hatted" designs). A roasted chicken hangs from the mast; a knife-wielding man tries to cut it down (nodding to the Dutch proverb, "Hang the roast and feast!"). A crescent flag flies, while an owl—symbolizing heresy—watches from a treetop.

Adrift, never reaching port. Today, it feels like a pre-apocalyptic tableau: nothing left to fear, everything sickly. "Suppose you could look down from the moon, as Menippus once did, on the countless hordes of mortals. You would think you saw a swarm of flies or gnats quarreling among themselves, fighting, plotting, stealing, playing, making love, being born, growing old, and dying. It is hard to believe how much trouble and tragedy this little creature stirs up, for he is so short-lived that oftentimes he dies before he can cause much disturbance." —Desiderius Erasmus, In Praise of Folly.

It is crazy that, compared with his "crazy" works, Bosch himself seemed to have led a different life: born in 1450 into an artistic family near Antwerp, he embarked on the path of a professional artist at the age of 13. Plain and regular, a competent husband, a devout believer, a model citizen.

After Bosch's death, many of his works were burned by the church on the charge of "immorality" (who remembers that he was a devout believer? !) Moreover, most of his works are not signed by hand or dated. Currently, only 25 paintings can be confirmed to be by Bosch.

2. Fools in Love: Wounded Again and Again

Who is the extraordinary fou? A scepter-wielding jester in motley? A truth-teller among the silent? A passenger on that drifting ship? Should he be trepanned, imprisoned, or fitted with Konrad Seusonhofer’s iron helmet? Or melancholy like Jan Matejko’s 1862 Stańczyk?

"Fools first appear in the Old Testament Psalms: those who deny God, thus placing themselves at the world’s margins," explains curator Élisabeth Antoine-König. Another type emerged—followers of St. Francis of Assisi. By the 14th century, court fools flourished, embodying royal wisdom’s antithesis. Their satire was tolerated. Fools became game pieces (chess, tarot). The exhibition displays early tarot cards. Later, the fool transformed into a subversive, libertine figure mocking courtly love. Then came the king’s jester, granted free speech and tied to pagan festivals...

If we approach from a more subtle perspective to easily interpret the theme of "madness", we can start with those "love affairs". A madman, symbolizing the measure of love, or going too far. From the earliest works, madness and love have been inseparable. For instance, that medieval copper water jug is captivating: Phyllis Riding Aristotle. There is no need to search hard to find various interpretations of this story, from paintings to this jar that is over 30 centimeters tall right in front of you. During that historical period, humor and satire dominated the theme of love.

At the same time, the passion in love is also a kind of madness that makes people lose themselves: just like the saying in medieval literature, "A hero cannot resist a beauty." The Knights of the Round Table must be accompanied by intense love, such as the romance between Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere;Tristan and Isolde’s doomed passion... The exquisite ivory boxes that have been preserved, as well as those illustrated manuscripts, all depict wonderful plots.

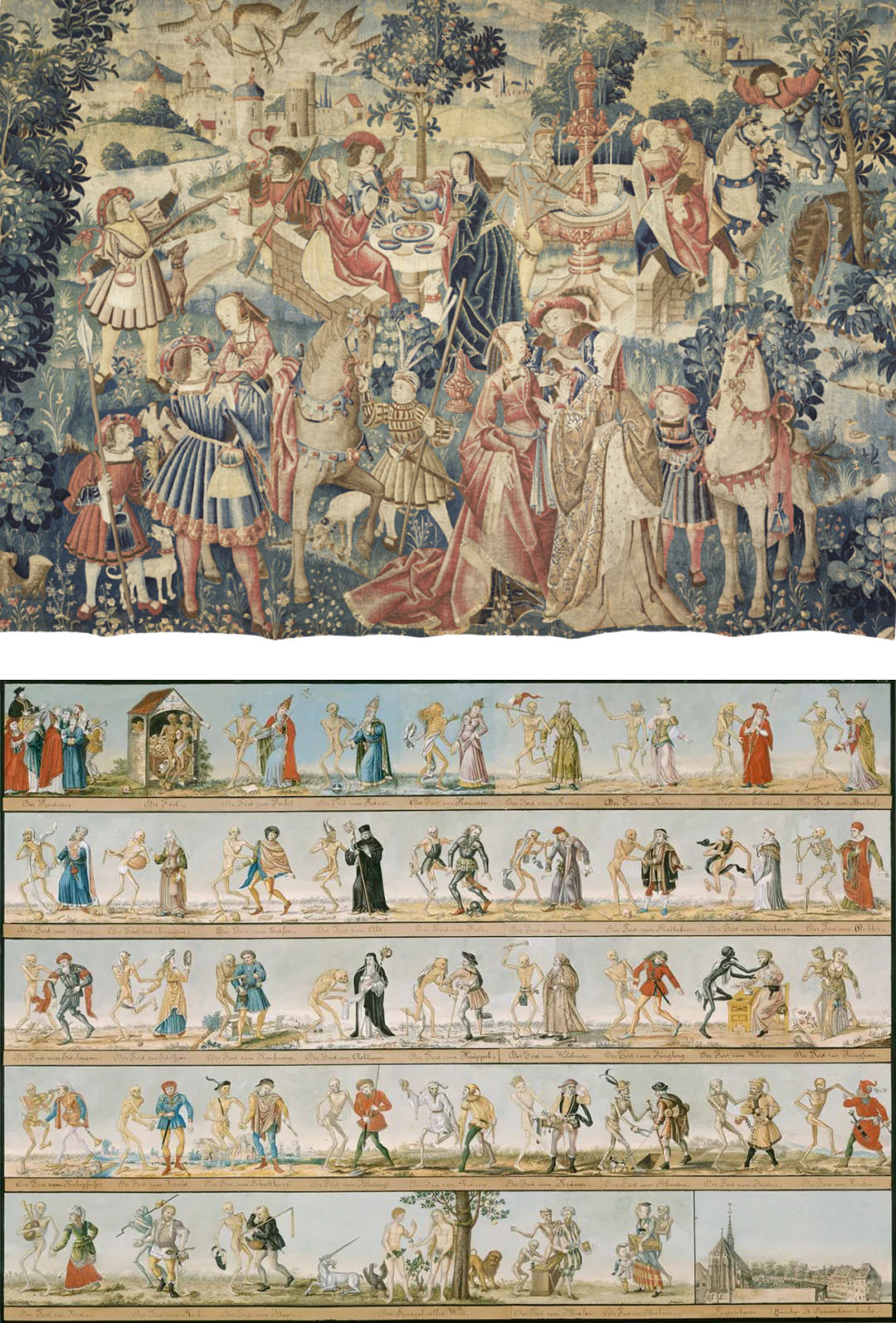

Soon, a new fool emerged—the third wheel mocking chivalry, flaunting desire’s raw side. Mocking chivalry and highlighting the sensual side of love, as curator Élisabeth said. Lust permeates gardens, brothels, baths... A tapestry titled La Collation (The Snack) shows satiated lovers; as food satisfies, hunger shifts to carnal craving.

Fools participate in, comment on, or warn against debauchery: Death awaits. Eventually, they join The Dance of Death (Danse Macabre), where skeletons lead popes, kings, and paupers alike—embodying vanitas: love’s futility, life’s fragility.

This is folly’s full arc: from philosophy to passion, heroism to hedonism, culminating in nihilism. Vividly, it teaches us romance’s nostalgic lessons.

3. Goya: What If I Were the Madman?

From the artist’s perspective: How does madness influence creation? Normalcy or marginality? As the Chinese saying goes, "No madness, no masterpiece." Many artists seem to harbor alternate universes in their minds. Foucault’s Madness and Civilization—"less about psychiatry than the philosophical value in artists’ lives and works"—and R.D. Laing’s view of madness as a "journey to higher consciousness" resonate here.

The Louvre’s exhibition ends in the 19th century, spotlighting Romanticism: Jean Desire Gustave Courbet, Francisco Goya, Shakespeare. Finally, Victor Hugo’s Quasimodo redeems the fou. "By then, madness became artistic self-identification. They wondered: What if I’m the madman?" says Louvre director Laurence Des Cars.

Romanticism wasn’t idyllic—it opposed classicism, prioritizing raw emotion, even ugliness. Goya’s The Madhouse(L’Enclos des Fous) exemplifies this. Based on his youth in Zaragoza, the painting reflects his own fears of insanity.

The asylum is desolate; inmates, chained and bathed in greenish light, wrestle or cower. A whip-wielding guard watches. Hidden since 1922, this work now resurfaces.

Few capture Goya well—his mind remains inscrutable. Foucault wrote: “In the painting of the Madhouse, Goya is confronting bodies prostrate in empty cells, naked bodies surrounded by bare walls... The man with the triangular hat is not mad, because he has covered his nakedness with an old hat. But in this madman who hides his shame, a savage and wordless youthfulness emerges from his muscular body, revealing a liberated humanity born free."

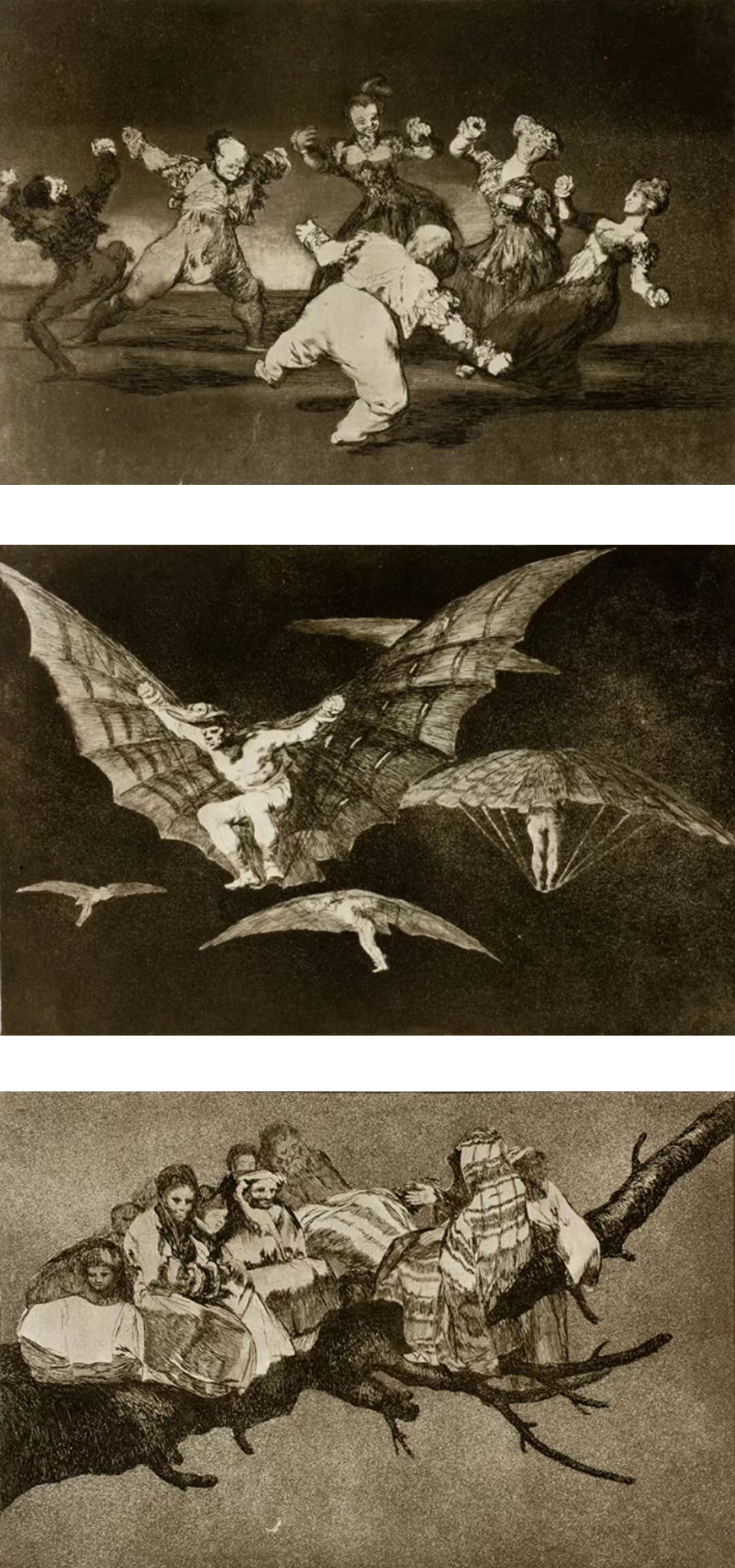

Los Caprichos (1797–98), Goya’s 80-print series, includes El sueño de la razón (No. 43). Later, Los Disparates (1815–23) explores another madness—not clinical, but linking us to witches, dreams, and old magic.

Los Caprichos is an 80-panel print created by Goya in 1797-98. El sueno de la razon is the 43rd painting and is the most famous in the entire series. And "Folly" (Los Disparates) is a print of Goya in the last years of his life. In 1824, when he left Spain for Bordeaux, France, he left these seemingly unfinished works in Madrid. "Rhapsody" and "Folly" present another kind of madness, not the madness of a madhouse, but rather a connection between us and the old order of the magical world, dreamlike flights, and witches who dwell in withered trees.

"Isn’t madness uniquely human?(La folie n’est-elle pas le propre de l’Homme ?)” —Blaise Cendrars

4. An Unexpected Performance

During the exhibition, a dance drama "Petites Joueuses" created by Francois Chaignaud was performed at the Louvre. For the stage setting, the medieval moat and tower areas of the Louvre were chosen. Shanio combined these architectural elements with dance, and naturally, the performance was also a response to history.

The light mirror and the large red balloon created a fantastical atmosphere on the stage. Exaggerated body movements, inspired by the postures of the madman in medieval art, especially imitations of “Danse Macabre” and "The Moor’s Pavane" - dancing at the edge of history, like the feeling of entering the edge world when we first step into the exhibition: Those 13th-century manuscripts, depicting strange, mixed and comical creatures, those images gradually spread, spreading into the floor and ceiling decorations of the Louvre...

I recalled my initial question: madmen, fools, psychosis... Then I thought of Russia’s "holy fools"—filthy, half-naked wanderers whose babble was deemed prophecy.

Conclude from the curator Élisabeth Antoine-König: Sacred and profane intertwine. We present an inverted concept, a mirror the fou holds up. It reflects both the other and ourselves.

Fools are everywhere (Partout sont les fous). Where is the sage (Où est le sage)?

I mentioned fou’s dual meaning. A coincidence: In Chinese comedy, "fou" (pronounced like the French word) means "wrong" or "not funny." Audiences shout it at failed jokes. Beyond this, how else might fou—as madness or folly—manifest today?

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Editor:Tiffany Liu

Writer:徐卓菁

Designer:Yizhou

Some of the images are taken by the author, while others are sourced from the internet