Everything Is Intimately Connected to the Life Before Our Eyes

Passing through the witty yet broadly documentary exhibition halls of Martin Parr's "To the Point" at Fotografiska, and then stepping into the visual realm of Rinko Kawauchi's "Distant Sparkling Stars, Twinkling in the Palm," the world seems to fall silent in an instant. The previously elevated excitement naturally subsides, retreating into a hidden corner of the heart. Without any verbal explanation or conscious reminder, the body seems to have already captured some mysterious and wondrous signal, urging us to gently settle the restless thoughts swirling in our minds and to receive, sense, contain, and internalize with pure tranquility.

In this equally dim exhibition space, Rinko Kawauchi arranges a series of large-format photographs emitting soft, shimmering light along the walls, like a row of radiant windows delineating a clear boundary at the edge of a dark universe. This boundary is not closed or possessive but open in both directions, guiding us toward the distant, subtle vastness of the cosmos while also drawing us back into the delicate, warm, sensitive, and fragile depths of our hearts.

These works primarily consist of Rinko Kawauchi's latest series, M/E, and her ongoing project, An Interlinking. True to her signature style, mundane objects from daily life—chains, fruits, the sky, green paths, pebbles, spiderwebs—are imbued with a soft hue through her lens, transforming into astonishingly poetic imagery. Amid these serene and tranquil scenes of everyday life, there are also glimpses that unexpectedly transport the viewer to distant vistas: rivers winding across the earth as seen from an airplane, a group trekking across an icy plain, a geyser erupting from the ground, microscopic ice crystals, or the moon peeking through the dark night...

These images suddenly shift our perspective, allowing us to gaze down upon our daily lives from an immensely grand standpoint. It feels as though they are posing a question none of us can avoid:"Why do I exist in this world, here and now?"In the dim space, these works resemble stars in the night sky, watching over us from afar.

During her trip to Iceland, Rinko Kawauchi witnessed geysers resembling the breath of the Earth, glaciers that transcend human time, and light slanting into the crater of a dormant volcano. These almost divine encounters, like sacred illumination, not only lit up the Earth we share but also the time we are inevitably enveloped in, the existence of all things, and her own existence as a tiny individual. The light entering the dormant volcano led her to associate her position inside the volcano with the birth of human life. In her words, the"shape reminded me of a woman's reproductive organs. Gazing at this scene, I felt like a fetus cradled by the Earth, establishing an unprecedented connection with this planet."

With this context, we can understand why Rinko Kawauchi designed a spiral-shaped space with sheer fabric in the exhibition hall. Stepping inside, one feels gently enveloped by a hidden, tender force, as the dim atmosphere gradually dissolves the body and consciousness, merging them with the space. Human life is as crystalline and fragile as a dewdrop on a lotus leaf. We are thrown into this world without mercy, compelled to soar like swallows with all our might. Faced with the inevitable fate of vanishing, perhaps all we can do is, like a child, carefully grasp the traces of time as fine as sand, letting "distant sparkling stars twinkle in the palm." Perhaps this is the relationship between us and all things in the universe: "Everything is intimately connected to the life before our eyes."

The scenery seen with my daughter feels especially pure.

Upon closer observation, one might realize that within this small, faintly visible space lies Rinko Kawauchi's most tender and deeply cherished emotions. The series M/E stands for "Mother Earth," reflecting a shift in her perspective.

At the beginning of her photography career, she was an independent individual, unstable both socially and economically. This clearly had a profound impact on her: "Both my photos and I felt suspended." The dreamlike light permeating her works was not metaphorical for her: "For someone who couldn’t see the world clearly, this tone was just right. I also wanted to use photography to depict that indistinct middle ground." After her daughter was born, her gaze changed because of her daughter's presence. "While shooting M/E, my daughter was always by my side. So the scenery seen with her felt especially pure."

This might precisely be a "mother's perspective." In other words, Rinko Kawauchi naturally incorporated her care and worries for her daughter into her consciousness. When recalling her own childhood, she would instinctively wonder, "Is my daughter experiencing similar moments now?" When realizing "every day, every second, we are approaching death," she would think: "My aging and my daughter's growth are happening simultaneously; will the glaciers continue to melt in the same way until they vanish completely?" The image of swallows in flight naturally evokes her earlier work, Des Oiseaux. This series captures a bird's nest on the eaves of a dry cleaner near her home. One can clearly sense her projection of maternal emotions onto the swallows, revealing the deeply intertwined state of a mother's love, worry, joy, and concern: "If the fledglings fall from the nest, they might die. The fragility I feel in my child shares something in common." Such care and worry are also reflected in the images of children in this exhibition.

Looking back at her works from two decades ago—Cui Cui and as it is, which feature her daughter—I can’t help but feel that the core and most vital part of Rinko Kawauchi's visual world might be this very affection and concern for her family. Because this instinctual emotional bond pulls one directly back to the most vulnerable aspects of humanity, to the shared emotional ties between people and all things in the world. Perhaps this is what she meant by "from entities too vast to fully perceive with the naked eye to tiny individuals, there exists some mysterious connection."

Portraits of Family Daily Life

This also reminds me of the project From Our Windows, which I saw at last year's Kyotographie International Photography Festival featuring Rinko Kawauchi and Tokuko Ushioda. The project first invited Rinko Kawauchi to participate, who then recommended another female photographer for a duo exhibition. Tokuko Ushioda exhibited ICE BOX (冷蔵庫) and My Husband, while Rinko Kawauchi showcased Cui Cui and as it is. Rinko Kawauchi thought of inviting Tokuko Ushioda because of the latter’s 2022 photobook, My Husband.

Born in 1940, Tokuko Ushioda graduated early from the Kuwasawa Design School, studying under renowned Japanese photographers Yasuhiro Ishimoto and Kiyoji Otsuji. She gained acclaim in Japan for her series ICE BOX (冷蔵庫). In last year's exhibition, Tokuko Ushioda covered the entire first gallery space with oversized prints from ICE BOX (冷蔵庫), creating an overwhelmingly powerful presence.

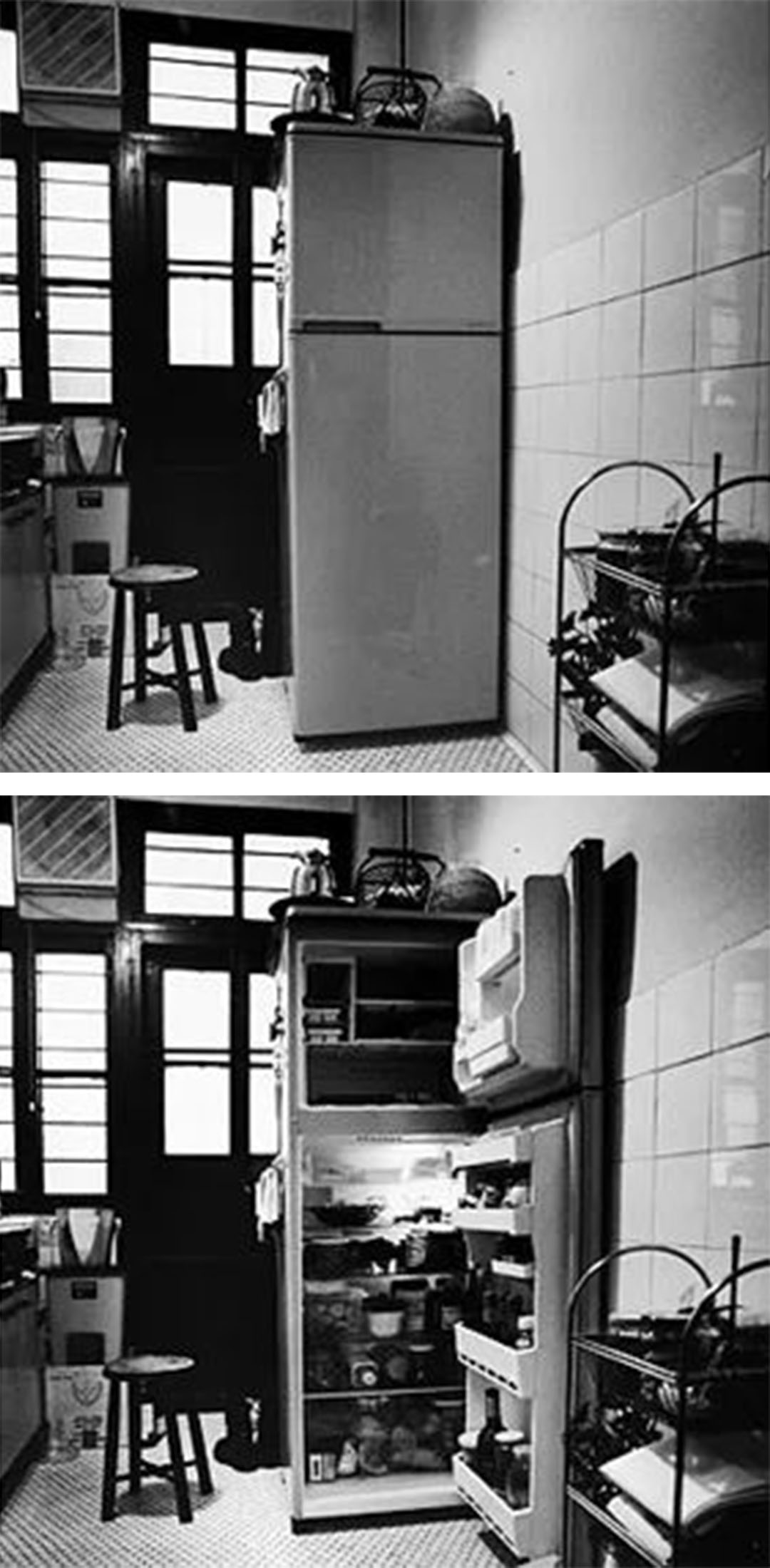

In 1980, after the birth of her daughter, Tokuko Ushioda and her husband, Shinzo Shimao (also a photographer), moved into an old Western-style house in Tokyo's Gotokuji neighborhood. One day, Shimao brought home a seemingly broken old refrigerator—a large, imposing appliance. At night, its motor would whirr to life like a living being, unsettling Ushioda. Faced with this uninvited guest in her life, she decided to photograph the refrigerator as a way to re-examine her daily existence. She adopted a methodical approach, capturing the refrigerator's overall form, its open and closed doors as a set, using 6x6 square-format photos with a calm and objective style. Afterward, she became curious about other people's refrigerators, and the project gradually expanded to include the homes of her landlord, parents, and friends. She continued this series for nearly 16 years, eventually compiling it into a photobook.

On the surface, this work might resemble typological photography in the Western tradition, yet it is neither classificatory nor driven by typological thinking. Instead, Tokuko Ushioda’s true focus was not the refrigerator's design but the texture of daily life revealed through its use and environment. Despite its Uniform and orderly, highly standardized form, the series radiates a profound warmth of life. As a modern necessity, the refrigerator is intertwined with everyone's existence, forming a shared ritual of daily life. Precisely because it is such an ordinary object, we often overlook it, making the refrigerator an invisible witness to life.

Through Tokuko Ushioda’s lens, the refrigerator is no longer a lifeless machine but assumes a special role—a spiritual anchor safeguarding and sustaining family life, almost a divine presence. These hulking appliances, stationed prominently in homes, become symbols reflecting the unique rhythms of specific households. Photographing a refrigerator is akin to capturing a family’s "portrait." In many ways, a refrigerator embodies the basic contours of a family’s daily existence.

Moreover, the orderly and standardized photographic approach imbues all refrigerators (and by extension, families) with a certain equivalence. In other words, every household, regardless of wealth or status, is equal and equally deserving of attention and respect. Of course, such works may first awaken the subjects themselves to the importance of their own family lives. Reflecting on the era in which this series was created—the peak and subsequent decline of Japan’s bubble economy—it was a time when insatiable desires drove countless individuals to focus solely on external pursuits, single-mindedly chasing wealth and social status while neglecting the true essence of daily life within each home. Perhaps what this series reveals is precisely the wisdom of homemakers, who must constantly navigate and reconcile the mundane minutiae of everyday existence.

A Loneliness That Belongs Neither to Wife Nor Mother

To delve deeper into the reasons behind Tokuko Ushioda‘s creation of this series, we might find clues in the second part of the exhibition, My Husband. This was not a consciously planned project but a collection of photos taken intermittently over 40 years of daily life. In the gaps between household chores, driven by a photographer’s intuition, she casually captured these moments. For a long time, the photos lay forgotten in a corner, nearly discarded during a move until Shinzo Shimao intervened. Ironically, their lack of deliberate artistic intent perfectly preserves the authenticity of her emotions and state at the time.

On the surface, these photos depict the most mundane scenes: insignificant household items, idle views outside the window, children playing, her husband’s presence or absence in the home. Many were taken when her husband and daughter were away or asleep, without premeditation. Yet, within these fleeting glances, Tokuko Ushioda’s love, worry, joy, and loneliness as a wife and mother are naturally embedded. Reflecting on these images, she remarked: "Having a camera as my ‘small room’ gave me moments free from control. In the long years of photography, this was the freedom I saw."

Though titled My Husband, the series includes many images devoid of people. We can almost imagine her state when taking these photos—staring blankly at the room, her husband absent, her daughter asleep, a loneliness that belongs neither to wife nor mother quietly settling in. As photographer Yurie Nagashima observed: "With a young child and overwhelming work, Tokuko Ushioda suddenly found herself alone. These were quiet, somewhat lonely, yet deeply fulfilling moments. It was as if experiencing loneliness itself was a joy." It is through such savoring of solitude that one comes to appreciate life’s preciousness and beauty.

In the age of AI, as the world’s imagery is being redefined, photography remains a core element of contemporary art practice, education, and the market. The final chapter of the exhibition ”Another Avant-Garde: Photography 1970–2000”, titled "Photography Today," focuses on artists from the 1970s to the early 2000s who, while revisiting archives and acting as media archaeologists, continue to ponder photography’s allure and its impact on the human condition.

As we quietly view these works, we deeply feel the complexity of solitude and liveliness within a room. With each photo, a story spanning nearly 40 years gradually unfolds. To Rinko Kawauchi, "the mood and tone of this work align with Tokuko Ushioda’s earlier pieces, but the focus on family is stronger, resonating with ICE BOX (冷蔵庫). It felt like glimpsing her private life."

In essence, Tokuko Ushioda’s photography stems from valuing private life. Because she valued it, she needed to observe it clearly and calmly; because she valued it, she unconsciously used her camera—her "small room"—to collect life’s fragments. Returning to Rinko Kawauchi’s Cui Cui, as it is, and the works in this exhibition, isn’t this the same?

As Rinko Kawauchi puts it: "We share a common thread: the accumulation of time. We both married late, had children later in life, and before that, spent years photographing alone. In that process, we formed families—our teams. While I was slowly building my body of work, Tokuko Ushioda was doing the same." Though Tokuko Ushioda’s works are black-and-white, austere, restrained, and somewhat heavy, while Rinko Kawauchi’s are colorful, luminous, exuberant, and filled with beautiful illusions, the emotions and desires underlying their art are the same: care and worry for life and family, and the hope to attain freedom through photography.

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Editor:Tiffany Liu

Designer:Yizhou Shen

Photo:From Fotografiska and the artist himself