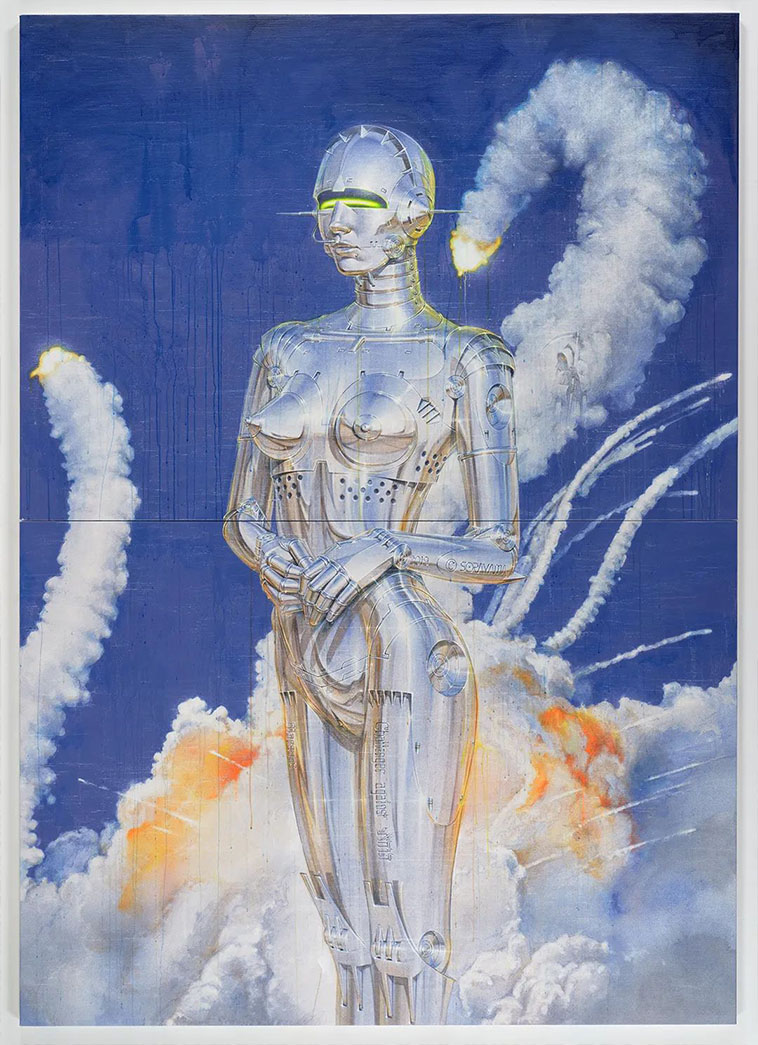

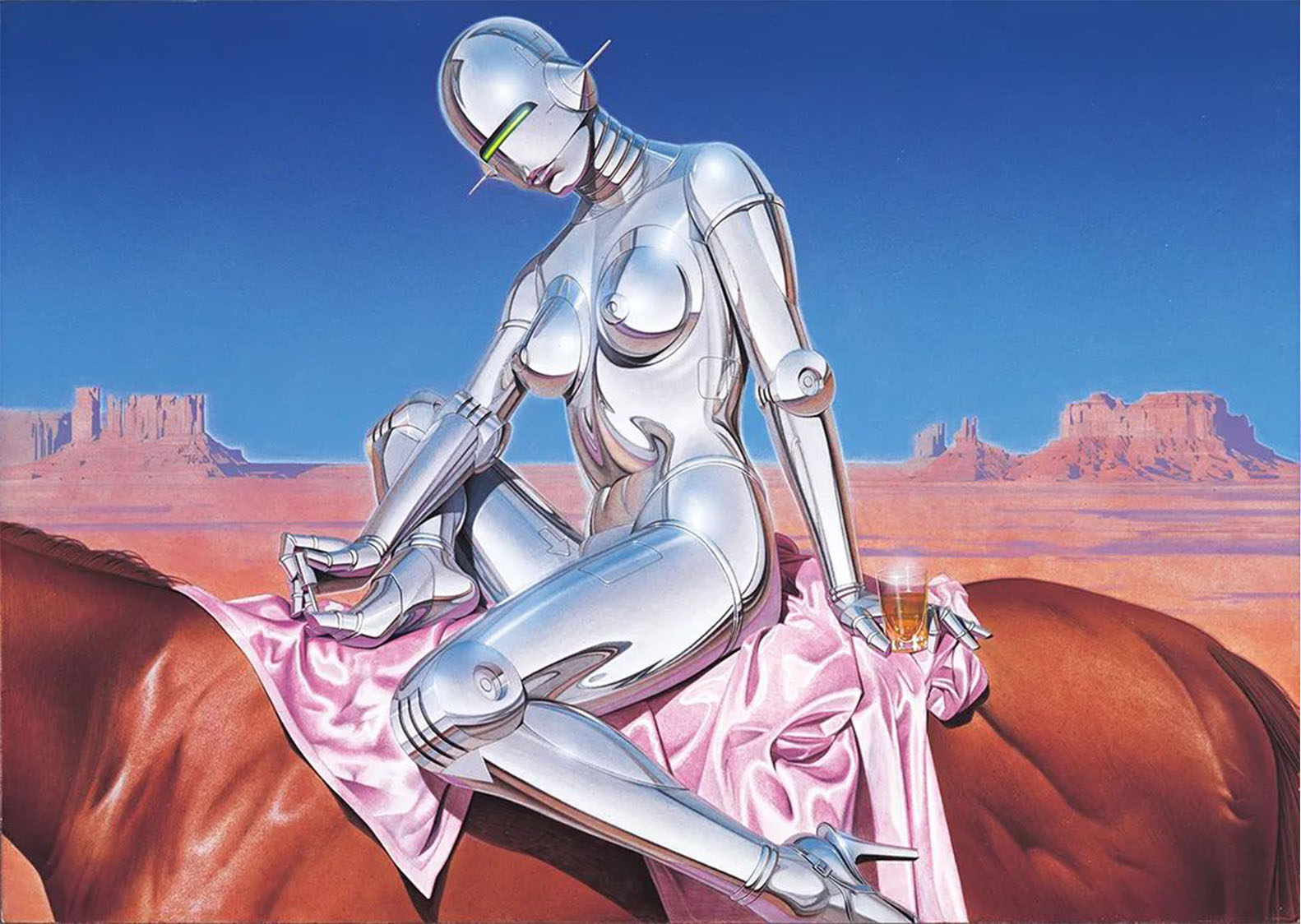

Unveiling the curtain at the Nanzuka Art Institue, a 12-meter-tall “Sexy Robot” stands in the outdoor plaza of Shanghai Huamu Times Square. Its metallic surface mirrors the neon skyline of Lujiazui—this iconic figure, once the centerpiece of a Dior show, now serves as the manifesto for Sorayama’s exhibition “Light, Reflection, Transparency”. Structured as a retrospective spanning nearly half a century, the exhibition traces the artist’s trajectory from his inaugural mechanical illustration for Suntory Whisky in 1978 to the breathing Mechanical Goddess within the mirrored chamber. The 78-year-old Sorayama dissects the DNA of human desire with metallic cold light.

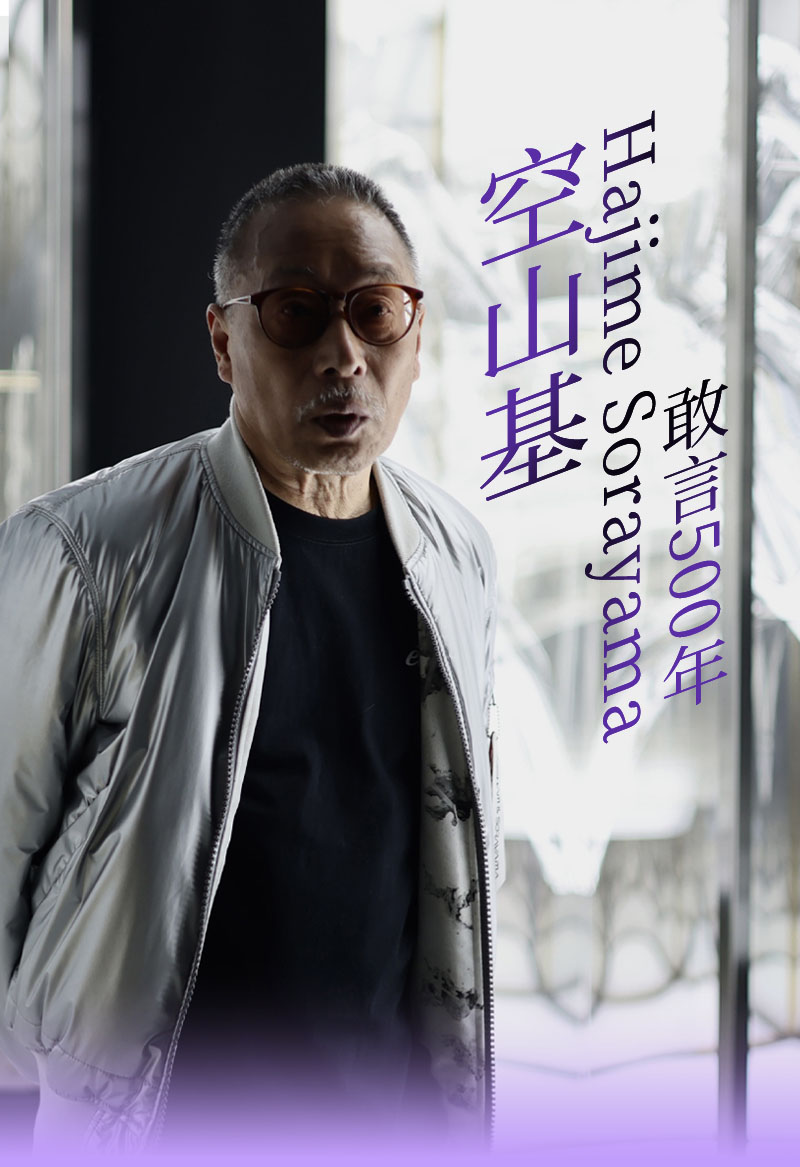

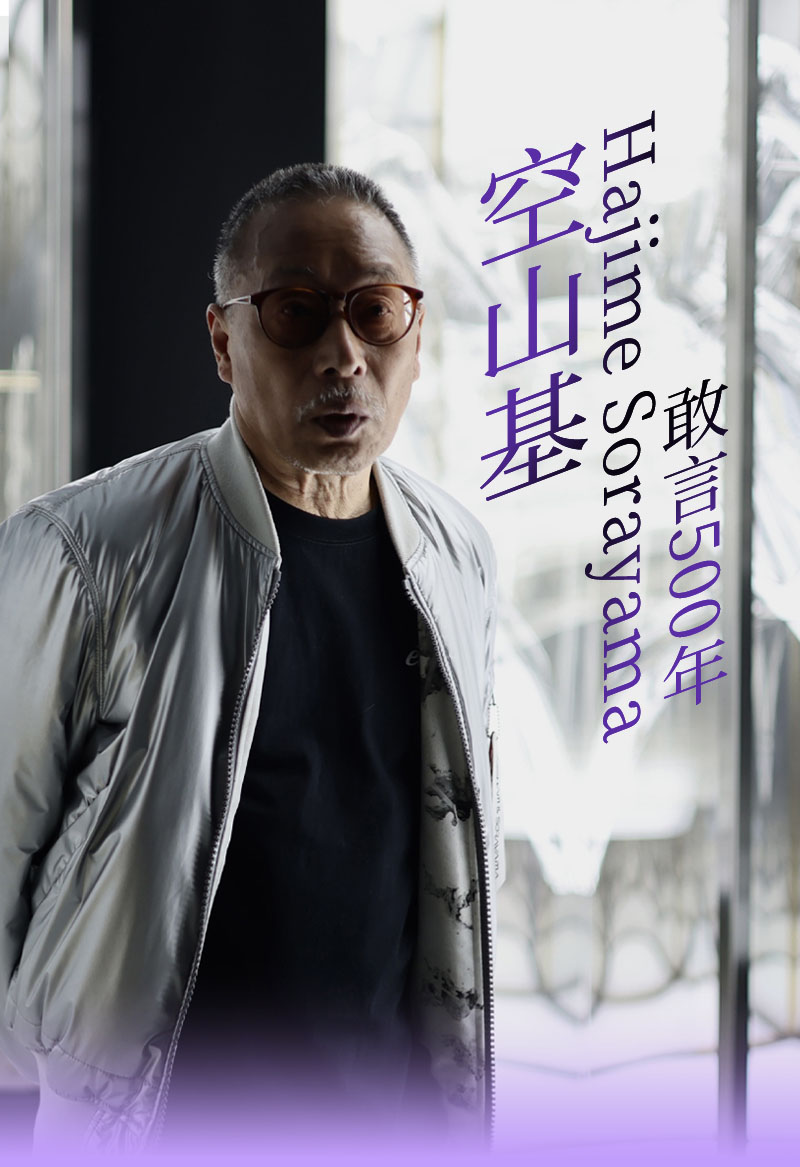

During the exhibition, Oui Art conducted exclusive interviews with master artist Hajime Sorayama and Nanzuka Art Institue founder Shinji Nanzuka, engaging in a rare three-way dialogue, adding thrilling new annotations to this retrospective celebration.

“Immensity is power, and also aw.” Watching visitors crane their necks at his monumental work, Sorayama explains his creative philosophy as a “holy feast of entertainment”. When mirrors refract spectators' images into the robot's joints, the revelation strikes: This is no longer just a future fantasy, but a cyber translation of the da Vinci shading method and the ukiyo-e prints of Katsushika Hokusai - a time-space distiller fueled by desire is roaring in the background.

A revolution sparked by a business commission

Sorayama's journey was an unexpected revolution in commercial commissions. In 1978, with the release of “Star Wars”, Suntory also hoped to commission him to design a brand-new mechanical image with a robot theme. When the conventional pin-up girl was rendered in chrome, the fusion of sensuality and industry triggered an explosive alchemy: “In the past, alcohol advertisements needed sexiness.”

Shinji Nanzuka identifies the breakthrough as "transcoding of media" "He elevated commercial illustrations into cultural symbols, using the airbrush to deconstruct the hierarchy between art and commerce." This approach peaked in 1999 with Sony's AIBO robot dog, whose exposed rivets deliberately mocked Japanese minimalism, offering a manifesto of “imperfect perfection.” The exhibited AIBO reveals Sorayama's creed: commerce accelerates art, while rebellion drives it forward.

Metallic Manifesto on Body Politics

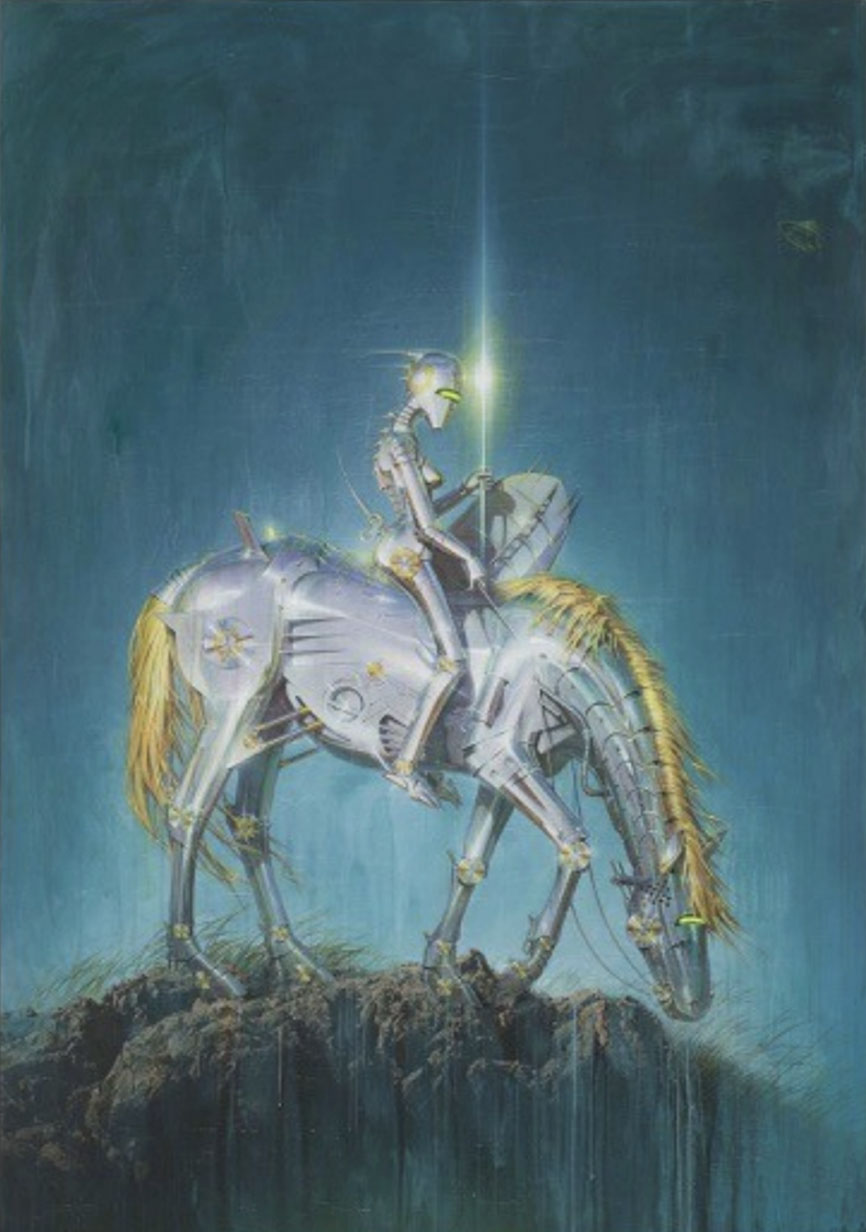

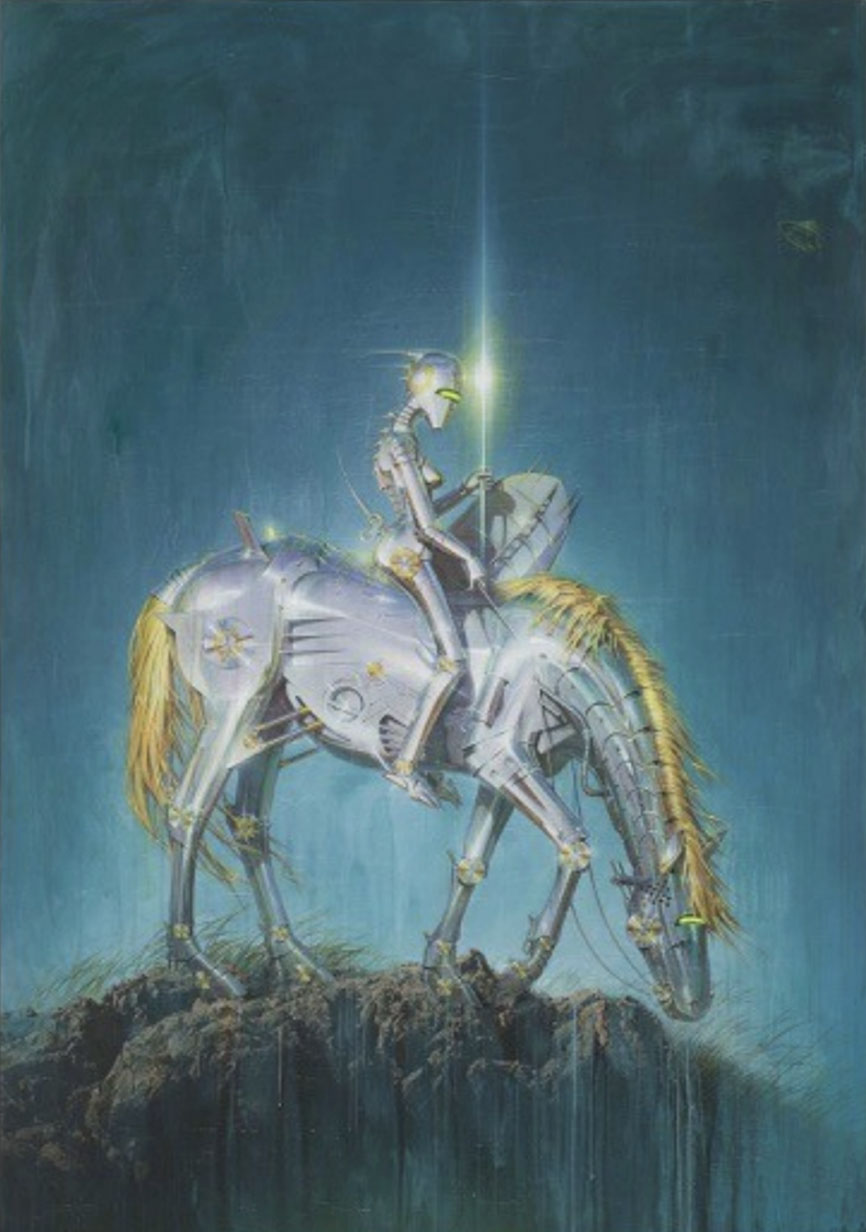

As cyber-aesthetics pioneer, Sorayama imbues cold metal with organic warmth. His "Sexy Robot" presents an ultra-precise industrial aesthetic, transforming human body curves into futuristic metal sculptures. The spinal arcs suggest both engineering rigor and organic fluidity. These works transcend traditional representations of the body, offering a new vision of humanity in the age of machines —where humanist spirit pulses through alloy and circuitry.

Nanzuka explains his evolution:“From fetish subcultures to transhumanist prophecy, Sorayama’s robots unexpectedly became symbols of human augmentation.” This prediction reaches its peak in the mirror room installation. As viewers encounter infinite reflections of mechanized bodies, Deleuze’s notion of the “body without organs” takes visual form: “Metal is the vessel of desire, and the vessel eventually reshapes the desire it contains.”

Cyber Rebirth of Eastern Aesthetics

Viewing Sorayama's works as a mechanical variant of Japanese aesthetics' "Yūgen" is by no means an exaggeration. His meticulous polishing of the luster of the metal skin is akin to the "tsuketate" technique used by Rimpa painter Ogata Kōrin to capture the halo of the moon with gold foil - through a 60-layer spray gun gradient to simulate the oxidation process of silverware, causing the cobalt alloy surface to generate a "breathing sensation". This obsession with the vitality of matter forms a cruel contrast with the void and light generated by AI-generated images in the GPT era: the former is the taming of materials by artisans, while the latter is the colonization of vision by algorithms. Metal is both a covering garment and an open window. His work reinterprets the “hidden-yet-revealed” poetics of Katsushika Hokusai's erotic prints Kinoe no Komatsu,using industrial materials.

The Sexy Robot's chrome curves are often misread as Western pin-up derivatives, but conceal Eastern philosophy. The sensual quantum state is manifested in the hydraulic joints of the androids. Sorayama deliberately left a 0.1mm rubber gasket at the joints, allowing the metal to undergo elastic deformation similar to skin when under pressure. This "harmony of hardness and softness" design stores desires within the fissures where hardness and softness interpenetrate. When viewers gaze at countless androids in the mirror room, it is actually the cybernetic realization of the Eastern tradition of ""mind contemplation"(观心) - desires are confirmed as the subject in the self-reflexive gaze.

"Infants and birds unconditionally surrender to light. My brain will forever consider metal the ultimate sensuality." Sorayama 's confession reveals the most brutal truth of the GPT era: When humans lose their sensory acuity due to habitual thinking, only those clumsy, vulnerable, and metal-covered bodies that can be scratched by rust, and those that need to be looked up at, can re-activate the original neural potentials.

Q1: Mr. Sorayama, your earliest metallic robot figure was created in the late 1970s for Suntory. Could you share the inspiration behind this design and how the project came about?

I heard the news that “Star Wars” was going to be released, and then I was asked to draw a robot for Suntory's whiskey advertisement. I've always liked metal, and I thought I could do it, so I accepted.

スターウォーズが公開されるというニュースを聞いて、サントリーのウィスキーの広告用にロボットの絵を描いてくれという依頼があったのが最初です。金属は昔から好きだったし、描けると思ったので受けました。(日本語)

In 1961, Yuri Gagarin's Spaceflight, and the subsequent moon landing achieved by the Apollo program, sparked a huge wave of “Space Age” industrial design represented in the 1960s and beyond, represented by figures like Eero Aarnio, Eero Saarinen, Verner Panton, and Pierre Paulin.

In the film industry, a series of works such as 2001: A Space Odyssey, Alien, and Star Wars were born before the 1970s, all centered around the theme of "mysterious and unknown cosmic exploration". Based on these influences, the works created by Sorayama should be interpreted more from the context of design or film rather than being understood from the framework of academic art history.

The Sexy Robot series by Sorayama does not originate from the serious art history lineage, but rather represents an evolved form of the "Pin-up" culture in commercial art. However, considering the creativity depicted by Sorayama has had an extremely profound impact on broader culture in the 21st century, it is reasonable to believe that its works also possess undeniable significance and power within the mainstream system of contemporary art.

Q2:What happened in the period between your robotic illustrations for Suntory and the development of the “Sexy Robot” series?

Pin-up girls (sexy photos of women) were used a lot in alcohol advertisements back in the days so, I drew that as women with metallic skin. It was well received, and people asked me to create more, so it turned into a series.

昔から酒の広告にはピンナップ(セクシーな女性の写真)が使われていたんですよ。私はそれを金属の肌を持った女性として描いたんです。それが評判が良くて、他にももっと描いて欲しいということで、一連のシリーズになりました。(日本語)

For Hajime Sorayama, this represented a natural and inevitable evolution. Sorayama, as an illustrator specializing in pin-ups, combined his love for metal with this style, creating female figures with metallic skin. This fusion elevated the pin-up context and introduced new value both in terms of design and the possibilities of the human body.

Q3: The 1980s marked a time when your work resonated strongly with pop culture, including science fiction films and fashion. How did the cultural climate of that era influence your artistic expression?

It seems that works like RoboCop were influenced by my work, and Mugler also said he was a fan of mine. Culture develops by influencing each other like that. However, living humans — my muses — are a far more important source of inspiration than movies or fashion. [laughs]

ロボコップなんかも私の作品から影響を受けているようですし、Muglarも私のファンだと言ってたので、文化はそうやってお互いに影響し合って発展していくものなのです。私にとっては、映画やファッションより生身の人間(ミューズ)のほうが、作品のインスピレーションとしては重要ですがー笑。(日本語)

I believe that, since the 1980s, the influence of Sorayama’s work has far exceeded the inspirations from which it originally emerged. Designs like those of RoboCop, and more recent works like Beyoncé's concert costumes or Louis Vuitton's “Digital Girl” campaign in 2015, show the ongoing creative impact of Sorayama’s work. This speaks volumes about the excellence of his work and its lasting influence.

Q4: In the 1990s, your creations expanded beyond the Sexy Robot to more complex mechanical beings. Why?

The “Sexy Robot” series I created presents a kind of sci-fi vision of human mechanical transformation. These works initially resonated only within a specific subculture, but have now evolved into more profound social practices - for instance, my friend Keroppy Maeda is dedicated to exploring body modification technologies. This phenomenon may suggest that certain once-perceived marginal aesthetic preferences could actually become a special driving force for social evolution.

ガイノイドといって人間が機械化するというファンタジーを描いています。当時はフェティッシュの人たちだけのカルトでしたが、私の友人のケロッピー前田のように、今では真剣に身体改造をしている人もいますし、まあそういう一部の反社会的な性癖が世の中を進化させることもあるということじゃないでしょうか。(日本語)

Sorayama was influenced by subculture of human body modification and developed his “Sexy Robot” series in the 1990s. Back then, this was mainly a fetish subculture, but today, with the advancements in AI, it’s gaining attention as a device for achieving immortality. It should be noted that although the artist himself may not have anticipated this development, the aesthetic system constructed by his works indeed provided a highly inspiring visual reference for related ethical considerations of technology.

Q5: Since the turn of the millennium, you’ve been using transparent “Sexy Robot” installations in your showcases. What led you to start incorporating glass as a material?

As seen in sci-fi films like “Blade Runner and Ghost in the Shell”, my work shares a strong aesthetic affinity with the depiction of artificial beings. This particular piece originated from a proposal by the NANZUKA team. When light reflects multiple times within the mirrored box, viewers are treated to a unique and visually engaging experience.

ブレードランナーとか攻殻機動隊など漫画や映画で人造人間を作るシーンがあるでしょ。私の作品は親和性が高いので、NANZUKAの提案で作ったのがきっかけです。箱の中で光が反射を起こすので、見ていて気持ちがいいんですよ。(日本語)

Sorayama developed three-dimensional works and installations to give viewers a more multifaceted and realistic experience of his world and aesthetics. He has always rejected highbrow, academic notions of art and proudly considers his work as entertainment. In this sense, I believe these installations, which draw people into Sorayama’s world, are entirely honest and true to his artistic intentions.

Q6:In the Japanese art scene, many artists have explored the theme of desire in depth — from photographers like Nobuyoshi Araki and Daido Moriyama to artists such as Makoto Aida and Tadanori Yokoo. How do you see your work positioned within this broader framework?

From the perspective of the inherent laws of artistic development, the human instinct for life and the impulse for artistic creation are inextricably linked. As a special group in society, artists often maintain a critical thinking towards the mainstream value system. This characteristic inevitably leads to their creations reflecting the original expression of vitality. Looking at the development course of art history, similar creative practices of this theme are widespread worldwide. However, due to the limitations of social cognition in specific historical periods, some works have not received the due attention and inheritance.

人間はSEXを否定したら生存できません。アーティストは社会性を無視して自分の衝動に正直であろうとする反抗分子なので、抑えられないんですよ。芸術の歴史を遡れば、世界中で同じような作品はあり溢れていますよ。ただ、社会が抹殺してきたから、あまり知られていないだけです。(日本語)

As Sorayama often says, life cannot exist without desire. Artists express themselves beyond societal restrictions and conventions, which is why they create groundbreaking works. It is particularly important to note that criticism of individual artists should be discussed diversely and individually, considering the culture, history, and social conditions of their respective regions. I believe it’s important to avoid making judgments based solely on singular notions of justice or social norms."

Q7: You have often spoken about your fascination with the beauty of metal and the female form. Could you please talk about the significance of desire in your creative process?

The unique aesthetic appreciation for the metallic luster is as pure and instinctive as a child chasing light. This perception is in harmony with the shaping of female images, and it is co-dependent with the core of my creation.

赤子と鳥は光に無条件に反射するんです。私の脳みそは進化しそびれて、永遠に金属の光をセクシーだと認識し続けているんです。それとマザコンのわたしの女性への憧れは同一なんです。(日本語)

This exemplifies the extraordinary aesthetic realm that Hajime Sorayama achieves. Under this sense of beauty, whether it is mechanical female figures, dinosaurs or real human bodies, all the creative subjects are endowed with a sacred artistic elevation. It is worth noting that its works have received widespread resonance among young female audiences, which powerfully proves the profound aesthetic value of its artistic creation that transcends gender stereotypes.

Q8: Does the “Sexy Robot” features a distinctive body proportion?Is there a particular standard or inspiration behind these measurements?

They’re my ideal goddesses.That’s all I can say.

私が考える女神像です。それ以上に説明はできません。(日本語)

Q9: The exhibition includes a 12-meter-tall “Sexy Robot” sculpture. When people look up at it, the experience is completely different. How do you feel about viewers photographing your large-scale sculptures from every angle? How does the emotion of the mechanical robot change after it becomes huge?

Immensity is power, and also awe. I have always strived to bring a soul-stirring impact to the viewers through my works. To me, the essence of artistic creation is a visual feast - in this sense, this piece of work can be regarded as my masterpiece.

大きいことは強さであり、驚きです。私は自分の作品で人をびっくりさせたい。私にとって自分の作品は、エンターテイメントだと思ってますので、 その意味でこの作品は私の最高傑作の一つです。(日本語)

This giant sculpture was originally created for a Dior show in Tokyo in 2018. Afterward, it sat in our warehouse for over five years. It was only seen by a limited number of VIP guests at the show, so I’m thrilled that it is being publicly displayed for the first time. I am grateful for the support of the landowner and the Shanghai Pudong District Cultural Bureau during the installation process.

Q10: Early in your career, you transitioned from the advertising industry to the art world. Nowaday, such crossovers seem less common. How do you view the evolving relationship between advertising and fine art?

For me, the essence of creation has never changed. Whether it's commissioned work or self-initiated creation, I always maintain a pure creative attitude - NANZUKA defines it as an artistic work, while I am merely depicting the world I love.

私にとっては何も変わりません。同じです。NANZUKAがアートだと言って持っていっているだけで、私は仕事であれ、なんであれ好きな絵を描いているだけです。(日本語)

Q11: Younger generations are increasingly drawn to virtual experiences. How do you see the “Sexy Robot” evolving in the digital age?

I don’t know, so I would rather leave these imaginations to the young people.

さあ、私にはわかりませんので、若い人の想像にお任せします。(日本語)

Yes, our art gallery is also actively expanding the display dimensions of new media and innovative concepts, with a particular focus on enhancing the immersive quality of the artistic experience. In the long run, we even hope to create an art experience space that can rival that of Disneyland - although this sounds a bit fantastical (laughing).

Q12: The golden “Sexy Robots” in this exhibition are full of divinity. How do you imagine people will perceive this figure a century from now?

If there were more people like you who share the same passion, my works might be able to be recorded in the history of art. To be honest, my ultimate ambition is to be evaluated as more outstanding than Da Vinci five hundred years from now - although this is a rather wild dream (laugh)

あなたのように神々しいと思ってくれる人が増えれば、私の作品は歴史に残るでしょう。500年後にレオナルドダヴィントよりも評価されるのが、私の目標です。(日本語)

Sorayama himself refers to it as his daughter and goddess. A hundred years from now, humans like Sorayama’s “Sexy Robots” may exist. At that time, I hope his original works will be displayed in museums around the world.

Q13: This exhibition is themed around “Light, Reflection, Transparency” Could you elaborate on your curatorial interpretation of these concepts?

The title comes from concepts that Sorayama himself has discussed regarding his work. Painting light and transparency with the primary colors (plus white) isn’t easy, and in fact, it’s virtually impossible. Yet, Sorayama skillfully uses reflection and highlights to make us perceive light, which is a brilliant illusion. We sincerely hope that the audience will be able to personally experience the techniques and extraordinary aesthetic achievements that Sorayama spent his entire life challenging.

Q14: The exhibition is divided into multiple sections, each with a distinct aesthetic. Could you select a few exhibition sections and share with the readers their aesthetic design concepts?

This time, we are presenting video installations for the first time. Due to the space segmentation, we couldn't create a fully enclosed room, but I believe this new work offers an immersive experience of Sorayama's world.

Q15: As a retrospective of Sorayama’s career, this exhibition provides a comprehensive look at his artistic journey. During the curatorial process, did you uncover any overlooked details or gain new perspectives on his work?

This is the first exhibition to bring together Sorayama’s works from the late 1970s to his latest pieces. By reviewing the artist's creative journey spanning over five decades, we believe that viewers will be able to deeply understand his consistent aesthetic pursuit. In each piece, which details did he devote special craftsmanship to? Such exquisite discoveries will surely continue to emerge. We look forward to each visitor to the exhibition gaining their own unique insights.

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Editor, Interview:Tiffany Liu、Yoko Liu

Designer:Nina

Photo:Captured on-site at the NANZUKA ART INSTITUTE and Oui Art