In 1839, photography was born, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that it emerged as an independent art form, entering museum collections and influencing other artistic mediums with its unique aesthetics. As David Hockney noted in Hockney on Photography, discussing the inspiration of the "camera obscura" on painting: "I realized that what I was attempting was a kind of photographic creation seen through two eyes." The West Bund Museumin Shanghai , in collaboration with the Centre Pompidou's five-year exhibition project, presents “Another Avant-Garde: Photography 1970–2000,” a showcase divided into ten thematic chapters that highlight pioneering artistic photography from around the world. This exhibition systematically traces the artistic trajectory of contemporary photography, featuring nearly 200 works, including renowned masterpieces and lesser-known conceptual pieces. Through diverse perspectives, it reflects the multifaceted development of contemporary photography, sparking reflections and broader emotional resonance.

“Another Avant-Garde: Photography 1970–2000” marks the first large-scale presentation of the Centre Pompidou's contemporary photography collection in China. Known for its modern and contemporary art holdings, the Centre Pompidou began categorizing photography as a distinct medium after its opening in 1977, collecting works from the "first golden age" of photography—representative pieces from the interwar period, including modernist, surrealist, and constructivist photography.

Before this era, photography was primarily viewed as a documentary tool, with attention focused on the realism of photojournalism or the poetic expressions of pictorialism. In the 1970s, conceptual art emerged. As pioneer Sol LeWitt stated, "In conceptual art, the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work." With the rise of conceptual art, photography entered its "second golden age," breaking free from the confines of documentation and expanding into more diverse artistic territories. “Another Avant-Garde” focuses on this period, when artists began to treat photography as a medium for artistic expression, redefining the motives, actions, and outcomes of "photography" through deliberate contemplation.

Curators Florian Ebner and Matthias Pfaller explained that the exhibition does not aim to create a new artistic genealogy but to connect parallel developments across different lineages: "Through the lens of photography, we offer a new way of observing and comparing. This creates surprising juxtapositions, such as the works of Sherrie Levine and Andreas Gursky, highlighting our fundamental questions: How does photography become art? How do artists utilize photography? What are the technical processes of photography, its role in society, and the possibilities of image representation."

Testing the Materiality of Film in the Analog Era

Film was an indispensable material in the early days of photography. In the 1930s, avant-garde artists like Man Ray bypassed the camera, creating "photograms" by placing objects directly onto film in the darkroom. Ugo Mulas experimented with developing and fixing film using his hands in 1972, producing The Laboratory, A Hand Develops, The Other Prints To Sir John Frederick William Herschel. The physical properties of film are repeatedly emphasized in the exhibition, from the 1930s to the present. In the chapter Questioning the Tool, artists from the 1970s and 1980s pushed the limits of film's potential, creating works that remain avant-garde even today.

During this period, technically perfect images were not the priority. In the practice of analytical photography, artists deconstructed the components and mechanisms of photography. German conceptual artist Timm Ulrichs' work Landschaftsepiphanen (Epiphanies de paysage)(1972-1987) selected an abstract frame from a pile of "discarded negatives," turning it into a lightbox displayed alongside the physical filmstrip, reflecting on the then-popular trend of large-scale color photography.

The film photography of the 1970s neither adhered to Henri Cartier-Bresson's humanist "decisive moment" nor inherited the refined traditions of pictorialism. Some artists redirected their analysis of tools onto the relationship between themselves and their instruments.

In 1971, independent curator and Avalanche magazine co-founder Willoughby Sharp organized the group exhibition Pier 18, where each artist was invited to create a project on a derelict Hudson River pier. Artist John Baldessari proposed bouncing rubber balls on the pier, instructing the photographer to capture the balls mid-air. Due to the unpredictable trajectories, the resulting images were compositionally skewed, subverting the pursuit of perfect framing and transforming photography into a record of performative action.

The “Another Avant-Garde: Photography 1970–2000” exhibition intentionally increased the representation of Chinese artists, as the development of Chinese photography during this period paralleled Western experimental approaches. For example, Rong Rong's East Village, Beijing No. 2—four black-and-white photographs documenting Zhang Huan's performance piece 12 Square Meters, in which he slowly submerged himself in a pond until only ripples remained—showcases this dialogue. Chen Shuxia, who used photography for early artistic exploration, created Searching for the Self in 1987, a series of four black-and-white self-portraits shot from behind, capturing distorted reflections in a mirror with a surrealist flair. These practices subtly influenced her later oil paintings.

The Mirror: A Metaphor for Photography

Jorge Luis Borges wrote, "The glass is watching us." When the shutter clicks, photography is never neutral—it carries the strong subjectivity of its creator. In 1989, French critic Jean-François Chevrier introduced the concept of tableau (French for "painting") into photography in his essay The Adventures of the Picture Form in the History of Photography, referring to large-scale, meticulously framed photographic works displayed in museums.

A pioneer of contemporary photography, Jeff Wall, is a quintessential representative of tableau. Drawing inspiration from billboards and street signs, he adopted the "lightbox" format of advertising to create what he called "cinematographic" landscapes in his photographic works. The first piece encountered in the “Another Avant-Garde” exhibition is Wall's monumental Picture for Women, a mirror metaphorizing the era: on the left, a woman faces the viewer with an indifferent gaze; on the right, the photographer himself triggers a large-format camera with a cable release, his eyes fixed on the woman. Modeled after Édouard Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, Wall uses mirrors to transform the original painting's spherical lights into rows of cold lightbulbs, weaving a montage of painting, film, and literary elements.

Juxtaposed with Wall's work are avant-garde photographs from the 1920s and 1930s, such as Ilse Bing's mirror self-portraits, which explore the camera as both tool and subject. "I felt the camera become an extension of my eyes, moving with me," said Bing, dubbed the "Queen of Leica" for her mastery of the 35mm Leica camera. The exhibition features her iconic Self-Portrait with Leica, where a mirror behind her captures a double image—one profile gazing away, the other looking directly into the lens.

Chinese photographers also explored the ontology of photography during this period. Jin Shisheng's Self-Portrait with a Zeiss Lens focuses on his reflection in a camera lens. A professor of the Urban Planning Institute in Shanghai, Jin began with pictorial photography before gravitating toward modernism.

Ugo Mulas' Photographic Operation: "Lee Friedlander: Self Portrait" attempts to verify another aspect of photographic reality. Sunlight casts the shadow of a pillar and the artist onto a wall, obscuring the photographer's face. Mulas said, "This verification is dedicated to photographers, who are most acutely aware of this issue and seek to overcome the camera's barrier—the medium they use and the way they understand it." Is the other side of the mirror shadow or light? Borges offers an ambiguous answer in his poem Mirrors: "I have been horrified before all mirrors / not just before the impenetrable glass,/the end and the beginning of that space,/inhabited by nothing but reflections.”

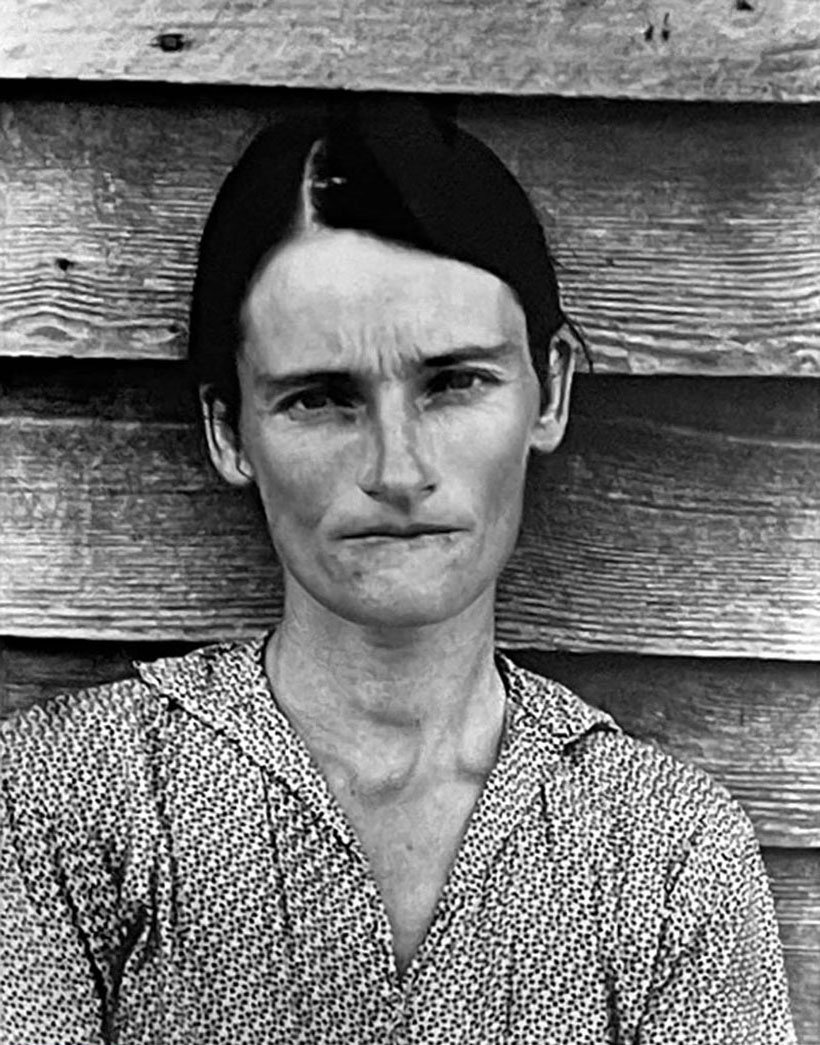

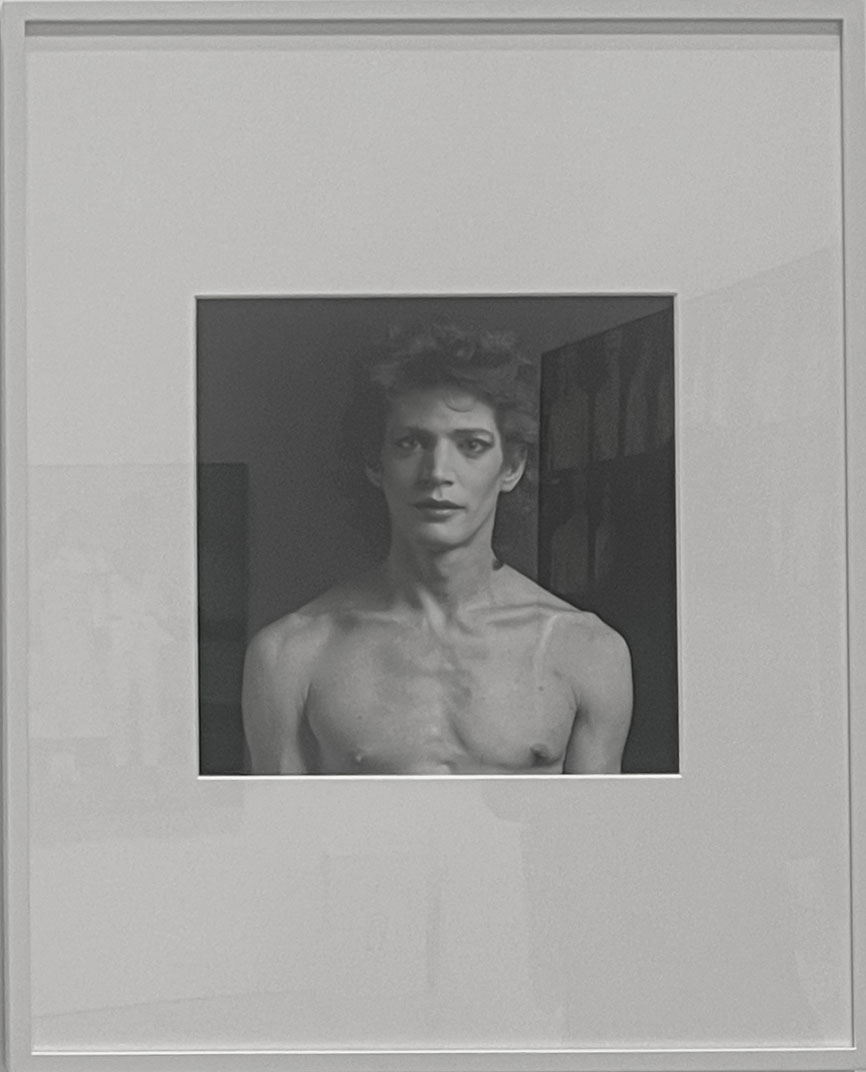

The Evolution of Portraiture: Prescribed Norms and Self-Presentation

Portraiture is one of the oldest genres in visual art. Susan Sontag wrote, "People want to see idealized images: photographs of themselves that show them at their best. When the camera gives them something less attractive, they feel reprimanded... The news that the camera can lie makes photography even more popular."

Portrait photography constructs the self and others through prescribed norms, but it has also become a tool for artists to question tradition. Thomas Ruff's large-format "mugshot"-style portraits from the 1990s, rich in facial detail, provoke questions about identity: What can a photograph reveal about an individual? Can facial images truly define a person? Suzanne Lafont's oversized black-and-white portraits strip away psychological or social dimensions, blurring the line between documentary and fiction.

For other artists, self-portraiture became a focal point for identity construction and gender issue, as seen in the works of Cindy Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Ma Liuming. The curators chose not to include Sherman's famous Untitled Film Stills but instead featured a lesser-known 1981 self-portrait, Untitled, which presents a vulnerable, sensitive female figure, prompting viewers familiar with her work to ask: Who is she impersonating now? Sherman's self-portraits, which initially mimicked Hollywood's female archetypes, dismantle the integrity of traditional portraiture—are these women from films or reality? Or a duet of truth and disguise? Though created over 30 years ago, these works resonate deeply with today's world, where more images mean fewer truths.

Breaking the Boundaries of the Flat Surface

By the 1980s, artists were no longer satisfied with merely reproducing scenes. While creating large-scale photographic works with various techniques, they incorporated painting, sculpture, and installation, expanding photography beyond printing, framing, and hanging. The materiality of photography was highlighted through multidimensional processes and materials.

Some avant-garde artists transformed flat photographic art into new hybrid forms, erasing the boundaries of the two-dimensional. Influenced by Malevich's geometric abstraction and land art, French artist Georges Rousse used vibrant geometric shapes or text to visually preserve disappearing buildings. His photographs capture these patterns only from specific angles, creating optical illusions that redefine spatial perception.

German conceptual artist Thomas Demand combines sculpture and photography, crafting models from colored cardboard, photographing them, and then destroying the sculptures. He likens his works to Japanese "haiku," simulating reality and reconstructing memory. Viewers must "read" his seemingly mundane subjects—bleachers, sinks, offices, or violin workshops—like texts.

In an interview, Demand said, "Unlike concrete, paper is ephemeral. It's beautiful, crisp, and fragile, perfectly suited to my work, flattening and unifying its elements. As digitalization makes photography easier to manipulate, it hasn't died—quite the opposite. So I feel compelled to study these private, everyday images."

In the AI era, the world's images are being redefined. For contemporary art, photography remains a core element of practice, education, collecting, and the market. The final chapter of “Another Avant-Garde: Photography 1970–2000”, Photography Today, focuses on works from the 1970s to the early 2000s, where artists act as media archaeologists, revisiting archives while pondering photography's allure and its impact on the human condition.

Sarah Cwynar rephotographed a 1960s manual on how to take good pictures, scanning the images to create "flawed" compositions. Wolfgang Tillmans' recent work Lüneburg (Self) resembles the kind of image one might delete from a phone album: a vertically placed screen becomes a new mirror, with the photographer's tiny reflection visible in a video call window. In an age where everyone uses phones to take pictures, countless screens multiply reflections, metaphorizing our decentralized, image-saturated era.

Chinese artist Wang Chuan uses pixels to explore the relationship between photography and painting, noting that all rapidly generated AI images are based on existing photos. Yet humans will never cease exploring the unknown, ensuring photography remains a powerful medium.

During the exhibition tour, the curators reminded viewers that great periods like the Baroque or Renaissance spanned two centuries. Looking back at the past 80 years of contemporary art, the diverse landscape of photography must be discussed within a broader developmental context. From silver halide to the AI era, photography has become an indispensable part of contemporary art, influencing other forms with its aesthetics. It continually looks outward to reflect inward, with beauty waiting to forge an emotional connection.

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Editor:Tiffany Liu

Writer:刘星

Designer:Nina

Photographer:Tiffany Liu、Yoko Liu

Some images are sourced from©West Bund Museum