Artist Chen Yujun's practice focuses intensely on exploring emotional connections between the individual and their homeland, as well as the relationship between natural and constructed spaces. Over the past two decades, through more than a dozen relocations, his current studio has become a sprawling repository of creative materials and life artifacts—layered and stacked like a palace of memories, serving in some way as an anchor for the artist's inner world. Every corner bears traces; each object might be the "loose thread" of a clue, tugging at which could lead upstream to wondrous vistas.

On a rare sunny day in early spring's lingering chill, we visit Chen Yujun's studio on the outskirts of Shanghai. The courtyard outside is paved with stone slabs and gravel, while the floor-to-ceiling glass by the entrance displays recent exhibition announcements. This space functions not only as his studio but also occasionally hosts exhibitions.

Every corner refracts the artist's personal journey and thoughts: the ground-floor painting area is divided by furniture and plants; the tearoom near the entrance is enveloped by broad-leaved greenery and orchids stacked overhead; the small fish in the aquarium were caught by Chen and his family during weekend river outings; the table bases and sections of walls are pieced together from reclaimed wood scraps.

The painting zone retains the original high ceilings, with long south-facing windows flooding the space with sunlight. Adjacent sits a small hut reminiscent of Zen courtyards, constructed from old wooden doors and planks—echoing elements from his past exhibitions. Two stone lion statues guard the wooden steps. A large painting in progress sprawls across the floor, deftly avoided by the studio's small black dog during its playful dashes.

Upstairs, several partitioned rooms continue the collage aesthetic below, blending wood and glass to maintain transparency. From the corridor, one overlooks the entire painting area. The first room features a sloping ceiling that descends to eye level, inviting close inspection of sculptures arranged like mythical beasts atop traditional roof ridges. "After reshaping the space, it needed the imprint of daily life to truly come alive," Chen remarks. He describes himself as a "compass": "I linger in each spot, sensing what needs adding or altering. Wherever my radar pings, that's where I settle for the day."

Building a Freely Growing Village

Chen recalls his first studio in Hangzhou, shared with his brother Chen Yufan: "There, I suddenly realized I had space—both as a creative vessel and the ultimate display medium. It later became the precursor to my debut solo Empty Room (Boers-Li Gallery, 2010), a fully realized comprehensive work."

His current studio took much longer to renovate, including a month-long pause due to stylistic uncertainty. Then the concept of a "village" struck him: How might art expand possibilities? He envisioned crafting a personal "village" to reignite passion for the unknown: "Within these sterile concrete walls, how could I make it feel like a garden, my village, my spiritual home?" Post-renovation, he repurposed accumulated installation materials, achieving catharsis.

The "village" concept unifies Chen's construction principles—layered and nested. He explains: "When you're lost in creation, suddenly glimpsing harmonious rhythms in the world points the way. But you must stay relaxed, let it grow organically." We discuss how classical Chinese garden philosophy emphasizes shifting views and the interplay of void and solid. His studio preserves this "unfathomable" quality, with corners visually layering upon one another. "For me, this space will evolve across future phases while its foundational structure—offering new perspectives from every angle, rich with natural complexity—already channels a village's interconnectedness."

Mulan Creek: Flowing Spiritual Homeland

Mulan Creek, a river flowing from Putian to the Sanjiang Estuary before merging into the Taiwan Strait, has nourished generations. Their ancestors drifted south across the strait to Southeast Asia, later influencing local culture in return—a blend of Nanyang (Southeast Asian) and native flavors that nested in Chen's memories as creative inspiration.

Since 2007, Chen and his brother have collaborated on the Mulan Creek project. In 2020, they invited media and scholars to their hometown for Return to Mulan Creek: wandering Yuantou Village, watching Puxian opera, feasting at banquets, absorbing local architecture and landscapes.

As a child, Chen loved perching on his ancestral home's high windowsill, observing a ditch below that flooded during rains. "Things carried by the river would linger there. That sill felt like a cozy portal to the world," he recalls. "In creation, I too seek such vantage points—where layers accumulate rather than confine."

Though Mulan Creek continues, Chen avoids merely appropriating "local" ties. Instead, for a decade, he's transformed his living spaces into sites of "locality." His 2022 solo Art House(艺术‘家’) at Long Museum (Chongqing) traced two decades of studio relocations as spatial narrative, symbolizing a summation of milestones.

The Path of Synthetic Painting

The current exhibition that Chen Yujun is planning is related to the comprehensive painting major he studied at the China Academy of Art back then. Regarding the concept of "comprehensiveness" in art, it is also a question he has been pondering over these years: "The comprehensive art I studied is actually a fusion of Chinese and Western elements. Two years ago, I returned to Hangzhou to visit my former mentor. He asked me how I view the issues of the East and the West now. I said that previously, I always felt as if I was on the fence between the two, sometimes wanting to understand, sometimes feeling very confused because there was still the thought of jumping off this wall and finding my own path in life. However, I don't have this feeling anymore now. The mentor asked, what kind of feeling is that? I said, I don't think I'm riding the fence. Maybe the wall is my path."

He considers synthetic painting "closest to the soul, temperament, and technical essence." Like all students, he initially emulated masters, risking the loss of his own voice. True clarity demands discipline.

"Let's see if today's self-reflection when looking at classics can still touch anyone at all?" — Four years ago, because he was going to Italy to do sculpture, Chen Yujun passed through New York's MOMA and deliberately went in to have a look around for self-assessment. When asked to list the works that still touched him, he replied: "First, it's a few rotten apples painted by Cézanne. It's a very small painting. When I looked at it, I was completely in awe and wondered why I'm still looking at this apple today? It felt like I was seeing the world anew, and it was as if the lenses had been changed, allowing me to see those simple things more clearly. When I was studying, I once admired him. After experiencing this chaotic world, looking back, it was still those few apples that moved me. Second, it was actually Picasso that I was somewhat resistant to at that time. Because he was so famous, I would have a kind of natural rebellion towards him. This time, I saw his sketches of female nudes, which were very simple and could be seen to be completed very quickly. And I also re-recognized that geniuses are indeed different. Third, I particularly liked Bacon. At the place outside the door, there was a portrait of a person through a steak hanging. When I was very fond of looking at picture albums in the past, I had many imaginations about Bacon. After so many years, looking at it again, I saw a more natural and simple expression that I hadn't realized before."

Like Paul Éluard's advocacy for "poetry that flows naturally(poésie de départ)" over "purposeful verse(poésie de but)," Chen's homeland manifests as a perennial stream in his work—a natural current propelling him to creative precipices where new energy surges. Great art possesses intrinsic order; its complexities deliver fresh experiences, even peril, embodying vitality and undercurrents.

01 Divination Blocks

Used in southern folk rituals to seek divine approval. When choosing between Xiamen University and China Academy of Art, Chen's father took him to a Putian nunnery. The blocks landed one yin, one yang—a "yes." He went to China Academy of Art and kept them.

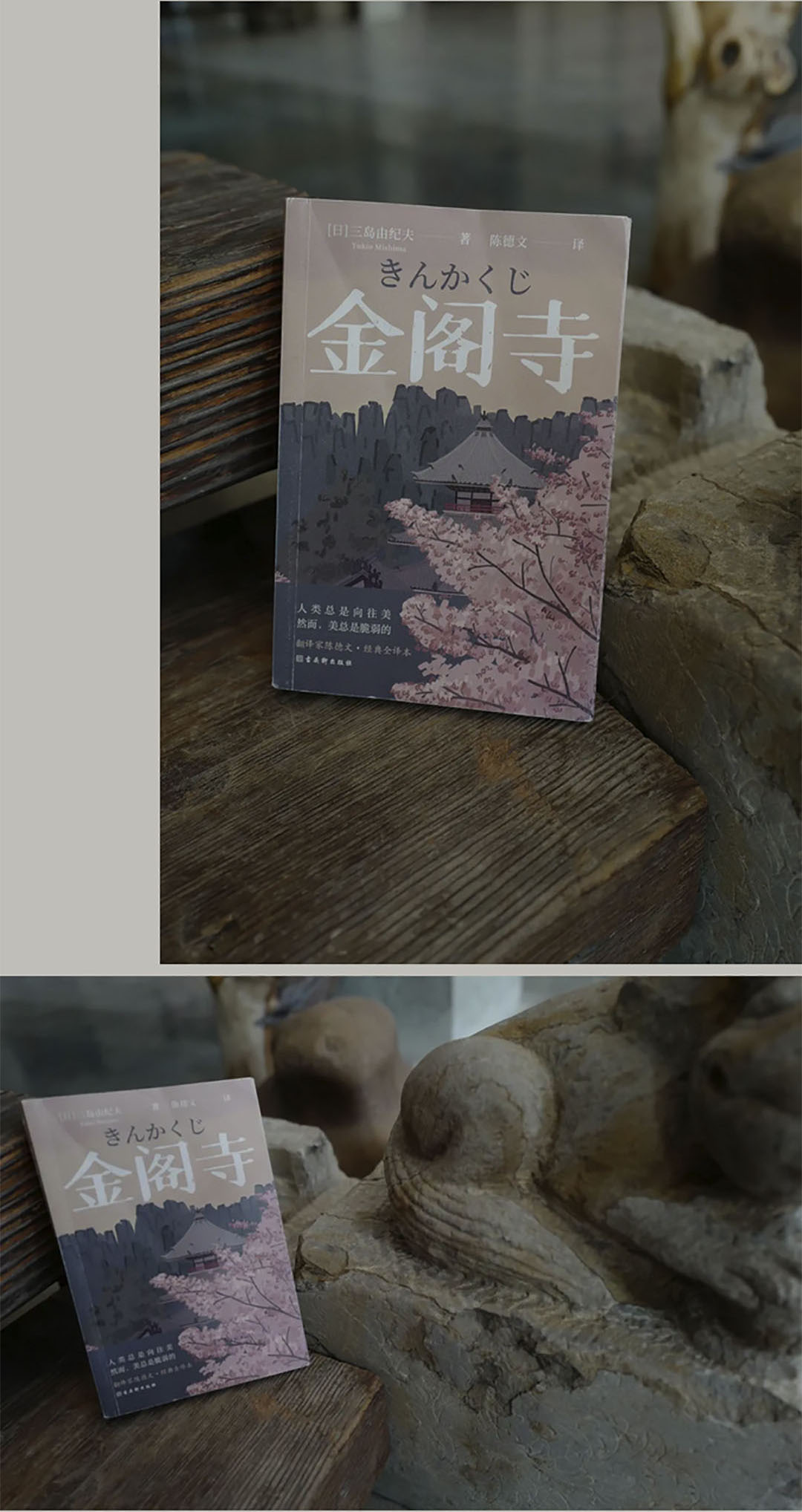

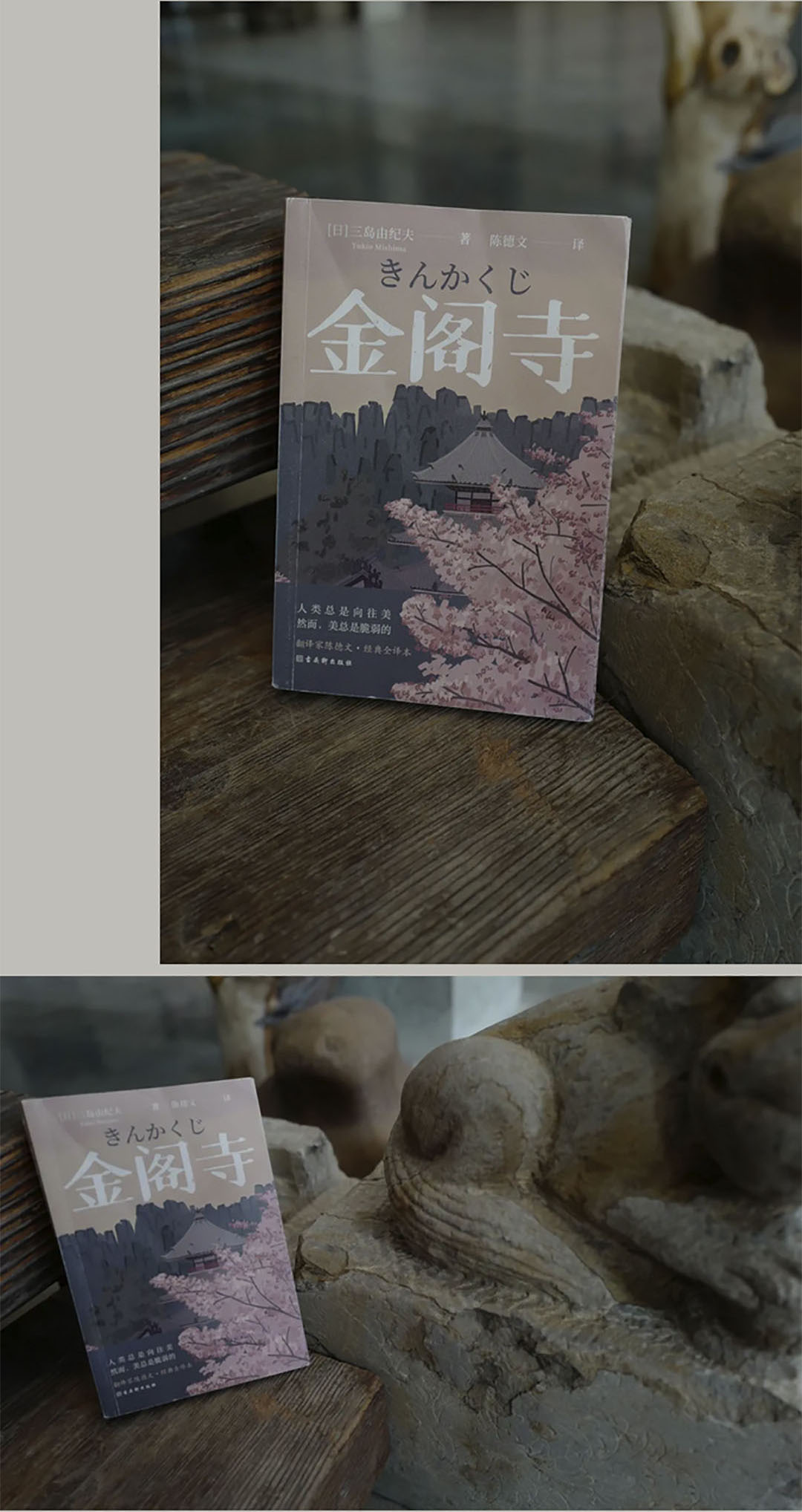

02 Golden Pavilion

"Beauty is the Golden Pavilion? Then I must destroy it." Reading Yukio Mishima’s The Temple of the Golden Pavilion —that terror of beauty's fragility, the urge to preserve or shatter what may not endure.

03 Lightweight Sculptures

As an experimental study on color, texture and form, these brightly colored abstract sculptures are delicately scattered throughout the studio, resembling plants growing from there.

04 Corn Teapot

The corn-shaped teapot that the parents used before has its corn husks transformed into a lid that gives the impression of flowing, elegant hair. This extraordinary imagination embodies the practicalist aesthetics of that era, being simple yet adorable.

05 Plane Model

Made during lockdown from discarded bottles and scraps.

06 Sony Camera

Artists often use this Sony camera to take photos, collecting various materials to help externalize their thoughts. He believes that it doesn't matter what kind of photos are taken, but the key is to be touched by something in that moment and use the camera to capture the vividness of that moment.

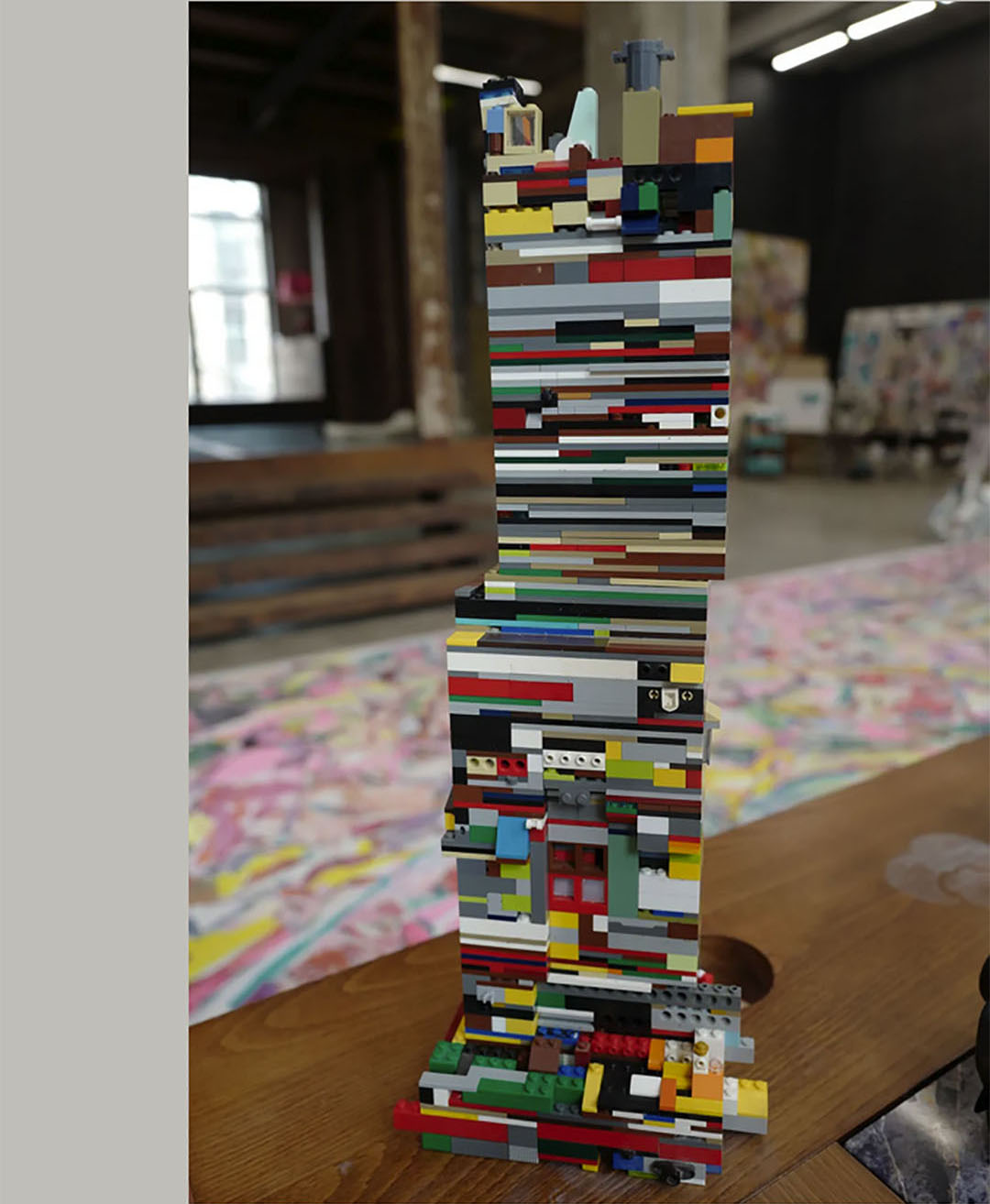

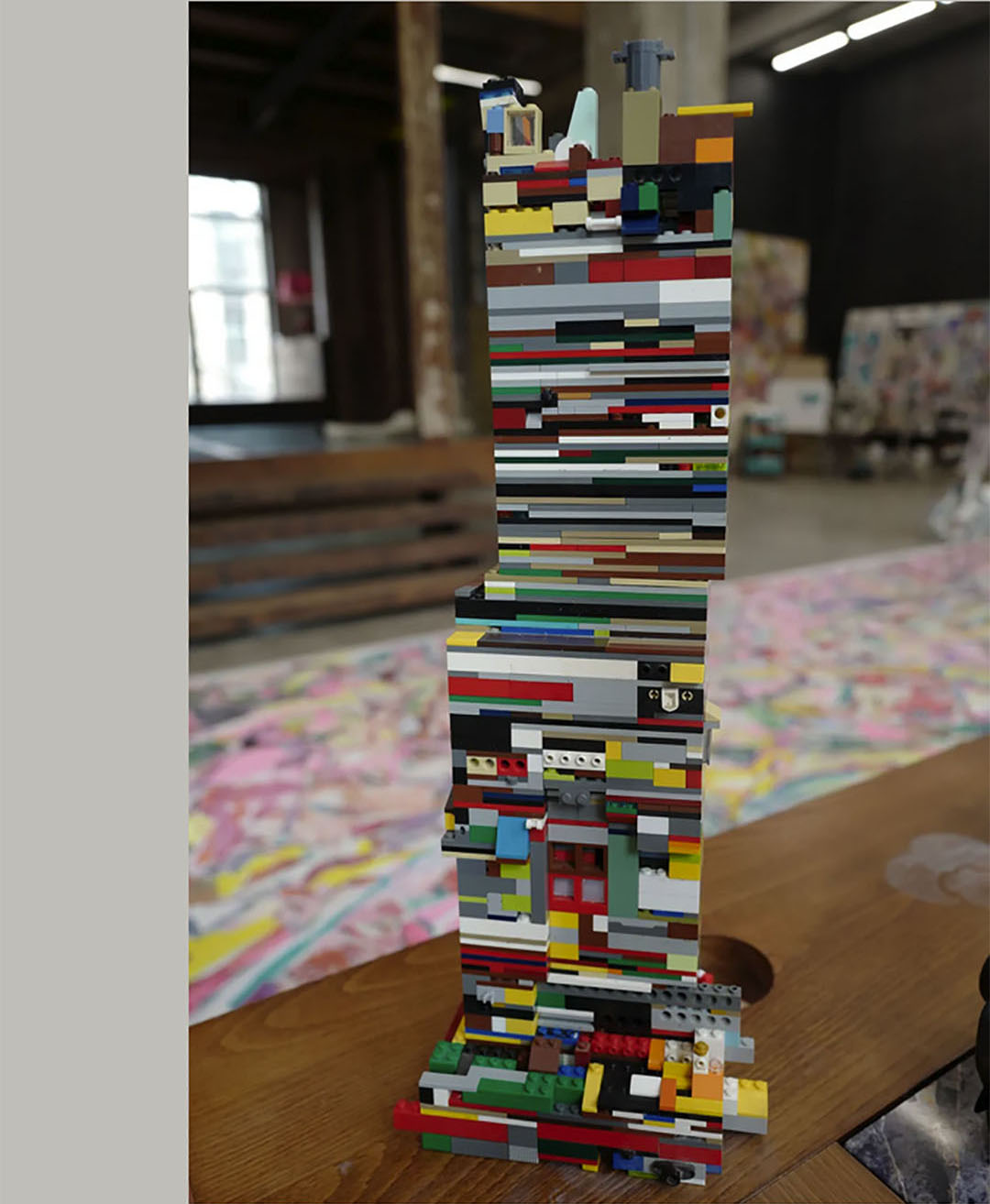

07 Lego Sculpture

Built spontaneously with his son's toys.

08 Lion Figurines

In the studio, there are various small lion-shaped figurines and sculptures. Most of them were brought from his hometown, Putian. They have undergone various transformations in folk culture, bringing about the lively charm of the folk.

09 Monkey King Statue

The revered Sun Wukong still thrives in Fujian, Taiwan, and Southeast Asian temples.

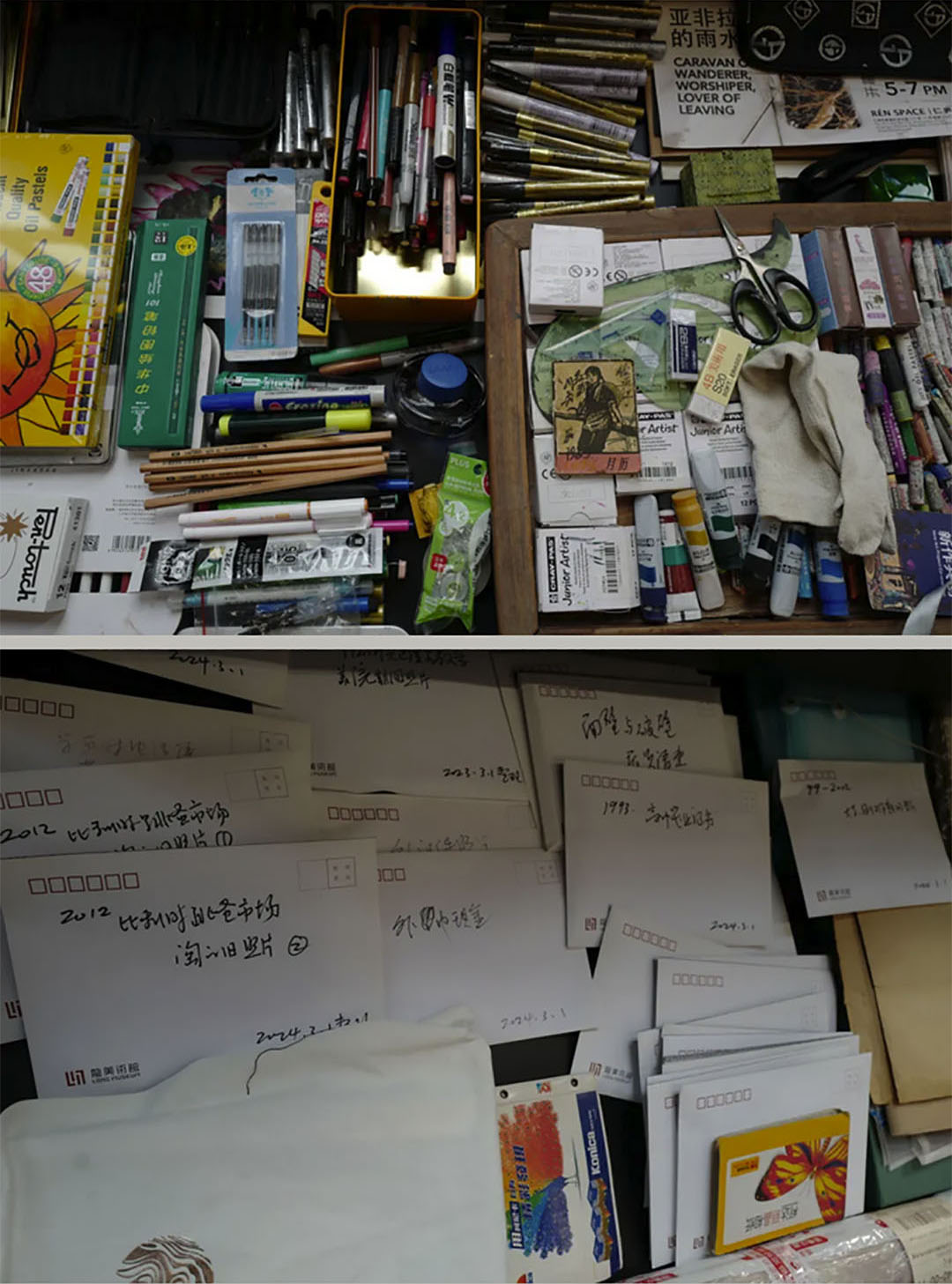

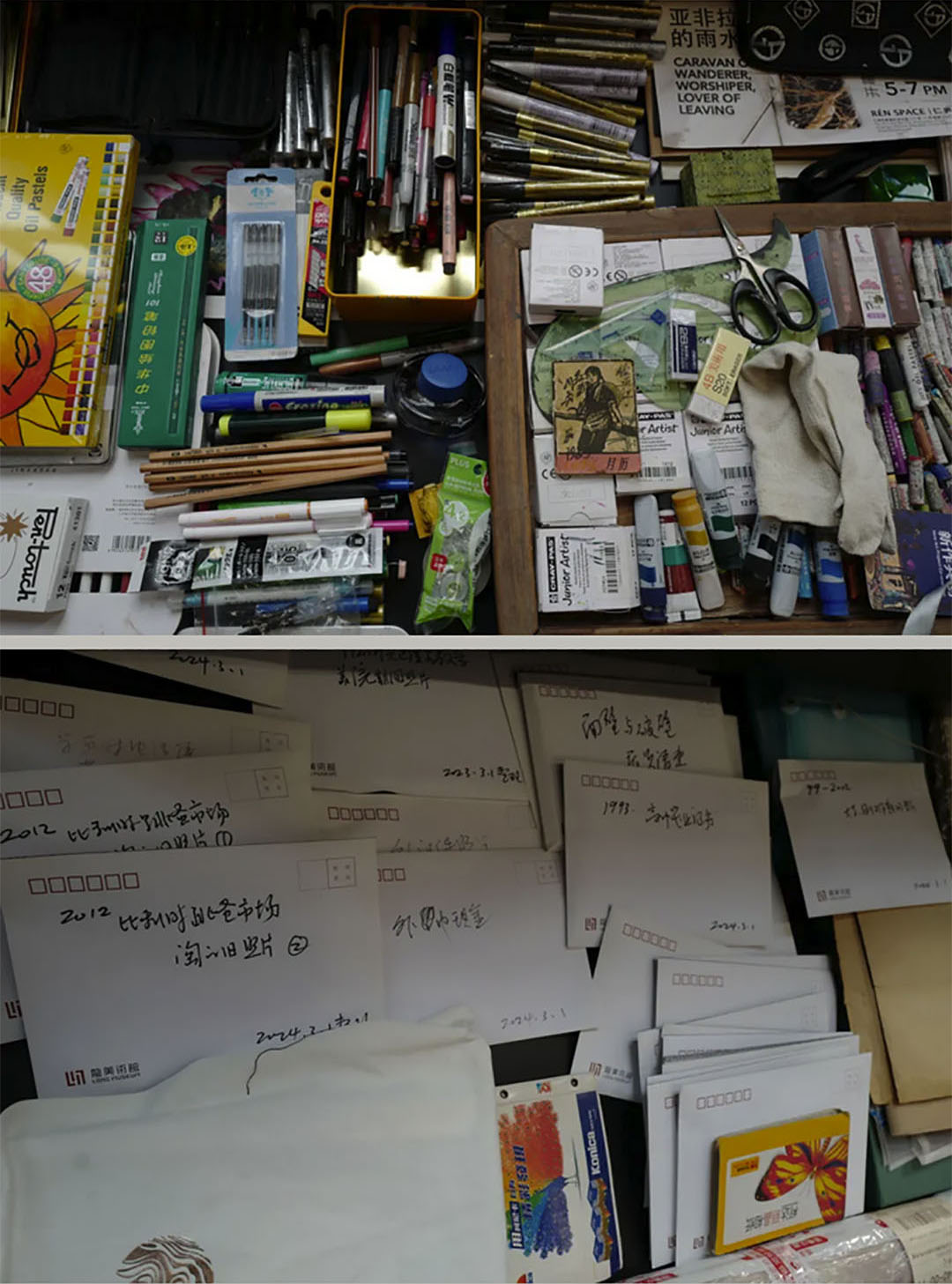

10 Memory Drawers

The photos from his student days, the old photos picked up at the flea market in Belgium, the buttons bought abroad... All of them were carefully sorted out by the artist and stored in drawers. He never wanted to throw them away. They were all "threads" of his memories, and they were the treasure trove of materials for his creative works.

Q&A

Q:From student-era tickets to furniture repurposed from installations—your studio brims with objects. How do you decide what stays through so many moves?

A:Choice is a process of unblocking, transforming it into something else will become the best material. Therefore, I always have a thought - all my things must be part of the work. Making full use of things is very interesting. Things are not just placed there as decorations; my greater interest lies in each item having a new composition and logic. Thus, many things will become hard to part with because once they are lost, their threads are cut off.

Q:What constitutes the uniqueness of your artistic practice over the years?

A:I thrive on exchanges with diverse fields. The richness and randomness of mundane life—interactions with neighbors, strangers, the city—feed me more than art-world discourse. Childhood experiences and cultural roots shape my physicality, while professional struggles carve distinct trails. Then there's the ineffable—like one's voice, impossible to fake.

Q: Your painting titles intrigue— Exile and the Kingdom, Vacillating faith... Later, you borrowed from literary giants like Camus ‘The Outsider or Proust’In Search of Lost Time… What inspires these references?

A:My creations do not start with a name and then proceed to draw. Instead, it's the other way around. First, there is an image, followed by a psychological feeling, and then the direction is sought. At this point, inspiration is needed, and often it only emerges at the last few minutes. Vacillating faith was when I stood among a pile of broken bricks in my hometown and felt that there was life beneath the stones and they were in a flowing state. This name came to me immediately and I felt it was right; The Outsider was created by having a friend take photos of the ruins and using those photos as the base for the creation. The ruins themselves were in an European style, and after their decline, they became a dialogue between the past classic and the present. However, they lacked human spirit. From a certain perspective, I think the writers' focus on the state of people and the rift between the current social civilization when they write, and then generating thoughts, suddenly I felt that the social and human relationships, responsibilities and obligations described in The Outsider were so perfectly in line with the work. The name is just an outer shell, it's just a way to let people enter this world, and there are many accidental elements.

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Editor:Simone Chen

Writer:刘星

Photographer:刘星

Designer:Nina