The city is a product of human civilization; it shapes human activity, and yet is itself continually shaped by it. Cities renew themselves at a swift pace, their scenes perpetually in flux. As Baudelaire wryly remarked, la forme d'une ville / Change plus vite, hélas! que le cœur d'un mortel—“the form of a city changes faster than the human heart.” Urban spaces are not only the stage for myriad human endeavors but also the enduring subjects of photographers’ attentive gaze, serving to anchor an inner order amid the swirling currents of change.

From May 8 to 11, 2025, PHOTOFAIRS Shanghai opened grandly at the Shanghai Exhibition Center. On the occasion of its tenth anniversary, Oui Art presents a selection of works that delve deeply into space through the medium of photography, reshaping the landscapes of the mind.

In today’s era, where concept-driven movements flourish in abundance, the allure of street documentary photography remains irreplaceable. Creators, their works, and audiences together compose a contemporary tableau of seeing itself, across different dimensions of time. Making its debut at PHOTOFAIRS Shanghai this year, Benrido—founded in 1887—evolved from a small rental bookstore into a company producing finely crafted color collotype prints, presenting works from pivotal figures in postwar Japanese photography, including Takuma Nakahira and Daidō Moriyama during the Provoke period. By the late 1960s, Japanese photographers had begun to recognize the alienation of refined imagery under commercial aesthetics. They shot against backlight, manipulated high-contrast tones and coarse grain in the darkroom, measuring their relationship with both self and city through body and camera. Their provocative ethos—the aesthetic of the “rough, blurred, and out-of-focus”—stood as a deliberate rebellion against the prevailing conventions of documentary photography.

In a society of the spectacle, where AI-generated images and social media algorithms erode the boundaries of “reality,” the marketing pitch “one filter makes you Daidō Moriyama” epitomizes the era. Viewed today, the Provoke works resonate as a prescient warning against the deluge of digital imagery: when photography appears to be the most accessible and immediate medium of expression, do we still possess the capacity, through a union of human and machine in creation, to experience moments of authentic, poetic resonance in a world so densely wrapped in images?

Almost simultaneously, across the ocean in the United States, black-and-white documentary photography dominated the scene, yet Saul Leiter captured the tender nuances of New York in color film. Within the labyrinth of rain- and snow-drenched memories, temporal markers dissolve, and the bodies of strangers in the streets often linger in shadow. Under the photographer’s gaze, color becomes a soothing agent for the emotions, imbued with the texture of a fading dream.

These mist-laden works recall the opening lines of Liu Yichang’s The Drunkard: “Rusting emotions meet another rainy day, thoughts play hide-and-seek in rings of smoke. I push open the window; raindrops wink on the branches outside. The rain, like a dancer’s footsteps, slides off the petals.” Street photography can forgo grand narratives and shed temporal coordinates; it is in the “memory labyrinth illuminated by incidental light” that perhaps this overly sharpened era most urgently finds its emotional de-ruster.

Theaters Endowed with Subjective Presence

Contemporary photographers, through a practice of “anti-reportage,” decelerate the pace of observation, allowing spaces to convey a sense of subjective consciousness and narrate their own historical iterations. As Candida Höfer, one of the renowned photographers of the Düsseldorf School, notes: “I am acutely aware of what people do in these spaces and how these spaces affect them. When no one is present, this awareness becomes even clearer; the absent guest often becomes the subject of conversation.”

As a student of the Becher couple, Candida Höfer regards theaters as social sculptures, photographing the interiors of unoccupied public buildings with a large-format camera to reveal the structure and details of architectural space. Benrido presents White Bench, 2019, while Matthew Liu Fine Arts exhibits her Bastou Building II, Mexico City, 2015—a spiral staircase viewed upward from the stairwell, its dark handrail coiling gracefully and dissolving into the surrounding white. In the photographer’s objectively composed works, spaces narrate their own functional, historical, and aesthetic stories; even the weathered walls of an abandoned theater hint at past grandeur within the landscape of ruins.

Also centering on architectural space, Lisson Gallery presents Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Theaters series, yet with a markedly different philosophical orientation and visual grammar. Begun in 1976, the Theaters series compresses tens of thousands of frames of a film into a single image by setting the exposure time according to the film’s running length: the long-exposure screen transforms into a square of white light, evoking the primordial energy of a world yet to emerge from chaos. The desolation of this “prehistoric” theater echoes the elemental state found in Sugimoto’s famed seascapes. Entering such a “Platonic cave,” the empty seats of the theater accumulate the superimposed presence and absence of spectators, leaving a pervasive void upon the floor.

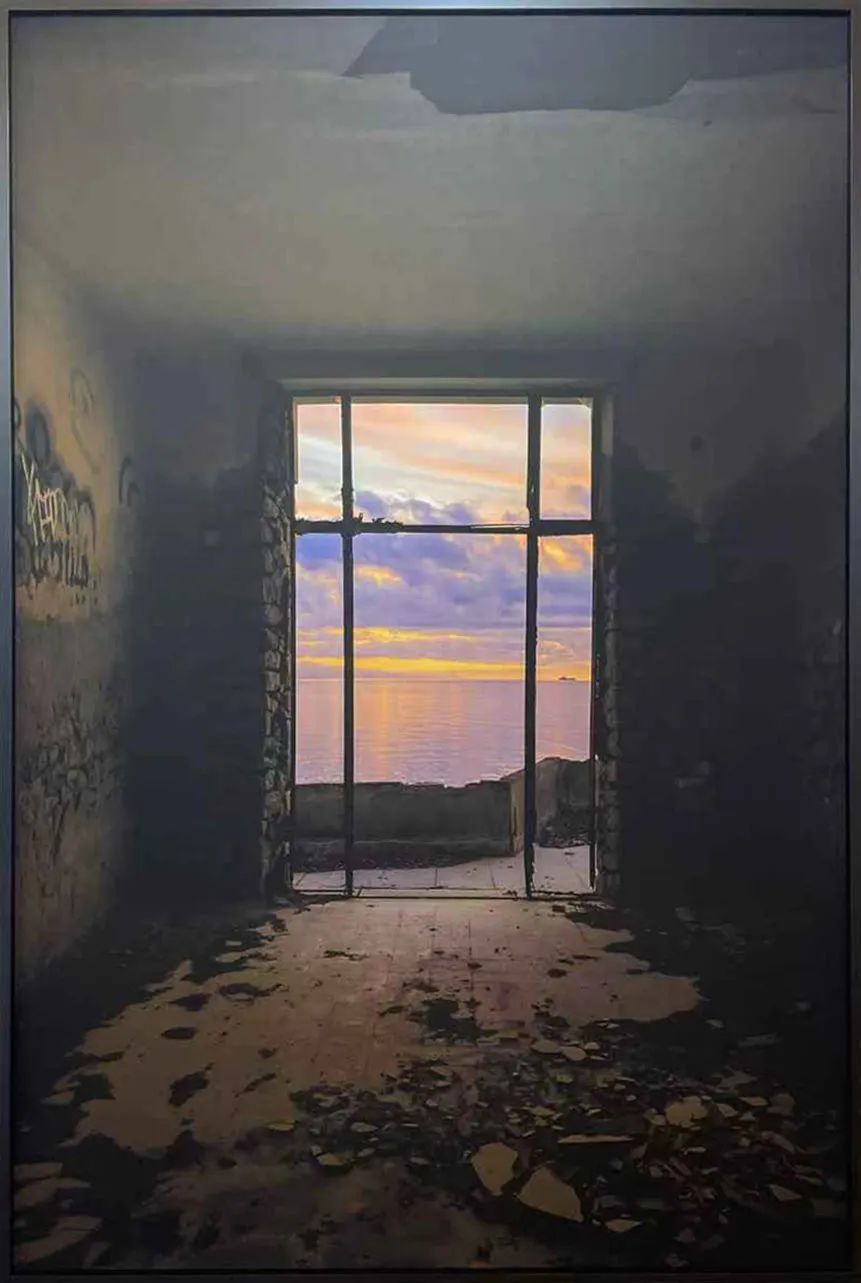

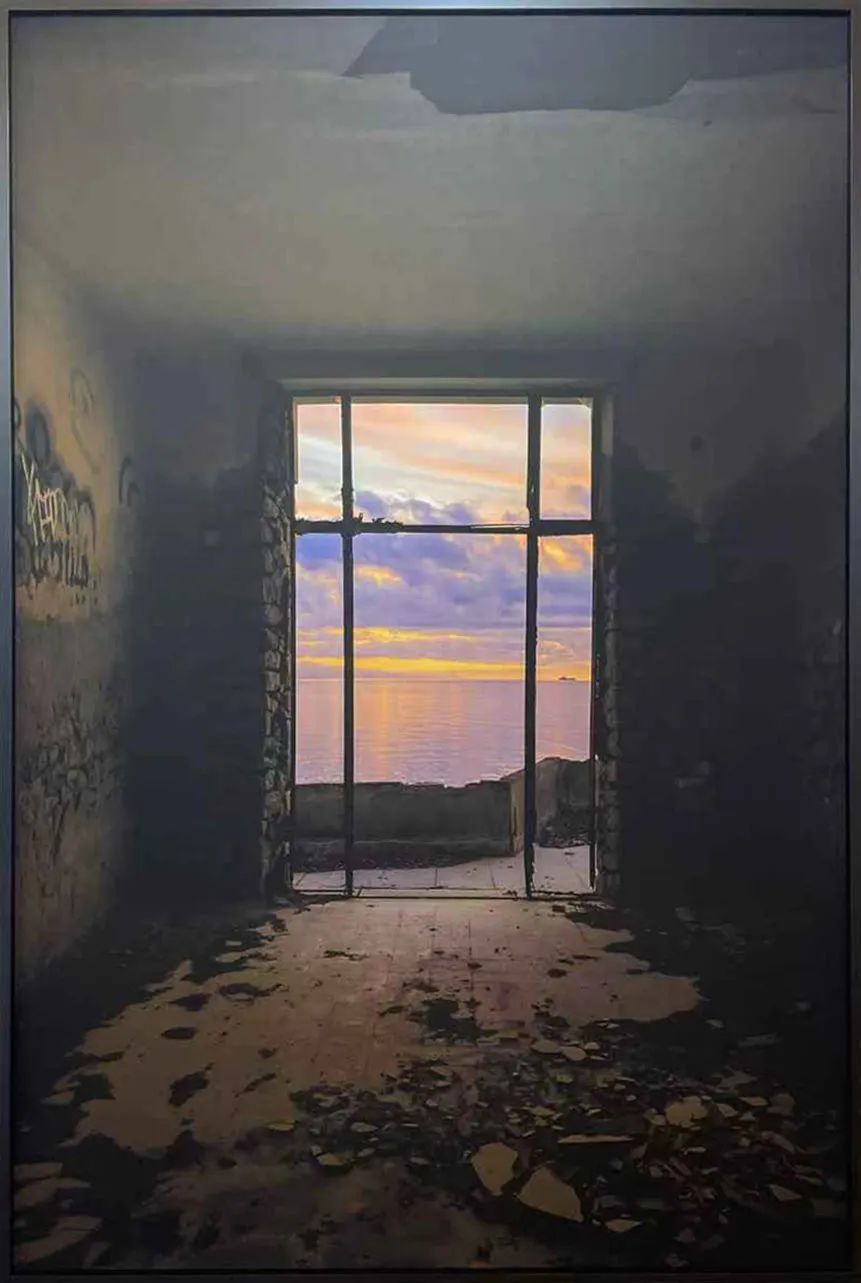

In a manner akin to long-exposure photography, Giovanni Ozzola intervenes in the urban landscape, frequently employing windows, mirrors, and water surfaces as reflective mediums to explore the ambiguous boundary between nature and the city.

He embeds landscapes within fractured panes of glass, allowing cracks and reflections to intertwine, conjuring illusions of layered, overlapping spaces. In his latest works, the horizon delineates the blurred edge between day and night; ruins meet the sea, indoor spaces are suffused with drifting sands, mist rises, night descends, and architecture becomes a vessel transfigured into light.

Roger Ballen’s absurdist theater blurs the boundaries between reality and imagination.

In the 1960s, inspired by the works of Beckett, Pinter, and Ionesco, he became attuned to the human abyss of absurdity. By the mid-1990s, he began creating his renowned “documentary fiction” works: graffiti on walls, inexplicable appearances of snakes, cats, chickens, wires, ropes, light bulbs… these elements serve both as props and as the stage of an absurd drama. The black-and-white, square-composed images unsettle and even evoke fear, charged with palpable tension. After the turn of the millennium, Ballen began employing drawing, color, collage, and sculptural techniques to construct ever more complex scenes, replacing human figures with dolls or mannequin parts, imbued with a playful mockery of carbon-based life: “People’s actions have no reason, no direction, and no ultimate purpose.”

In the award-winning documentary Visages villages, French artist JR, active on the international art stage, traveled through French villages in a small car alongside Agnès Varda, the grandmother of the Nouvelle Vague(French New Wave), blending play with creation. They photographed full-body portraits of ordinary laborers, transforming them into monumental black-and-white images affixed to buildings connected to the workers’ environments—factory water towers, dockside containers, and the like. JR is renowned for his large-scale black-and-white photographs that envelop architectural surfaces; his artistic practice merges photography, street art, cinema, and socially engaged interventions in specific sites. For this presentation at the PERROTIN Art Gallery, a portrait of a ballerina on a wooden panel is brought forth, a project originating from his collaboration with a ballet company, converting visual spectacle into public memory, extending into reflections on the city’s memory and the social theater it contains.

Dissociation and Reconstruction

Images are deconstructed and reassembled, with fragments of imagery serving as material, and the city conceived as an integrated whole. Through traditional collage or the incorporation of cutting-edge digital imaging techniques, urban landscapes are reconstructed—these works embody a reflection on modern civilization and the artist’s psychological projection of their own cultural identity.

Chinese photographer Xing Danwen, through her New York Panorama series and Scroll A and Scroll B, explores the complex relationship between space and the body, spanning from New York to Beijing. As a foreigner, she reflects on and perceives the transformations of the city, engaging in a sustained meditation on urban change.

CAVE-AYUMI GALLERY, in collaboration with the publisher ori.studio, presents Osamu Kanemura’s latest art book Gate Hack Eden. The book comprises hundreds of photographs, sketches, and video fragments, deconstructed and refined into countless homogeneous pieces. Kanemura, renowned for capturing Tokyo in the aftermath of Japan’s 1990s bubble economy collapse, photographs scenes devoid of people; within fragments of the city, wires twist in midair, corners are framed askew, and the orderly Tokyo appears disordered and austere through his lens. The new publication explores urban space as an integrated concept, probing the essence of materiality and its relationship with photography.

Yang Yongliang employs the scattered perspective of traditional Chinese landscape painting to reconstruct Manhattan’s skyline into a layered, cybernetic landscape.

His Parallel Metropolis series constructs an imagined urban landscape that intertwines cultural reflection with a futuristic city allegory: from a distance, the outlines evoke Eastern mountains and rivers; up close, steel scaffolding and cranes replace pavilions, boats, and bridges. Whether a “digital landscape” or a “future wasteland under construction,” neither creator nor viewer can ignore the inherent contradictions embedded within.

Cinema and Urban Allegory

The themes of urban migration and cultural reconstruction are closely intertwined.

A filmmaker’s photographic works, imbued with the effect of montage, capture a narrative instant, transforming the city from a mere “story backdrop” into a narrative protagonist. Wandering between narrative and lyricism, these works distill a single frame into an urban allegory.

Artist Yang Fudong has exhibited his “architectural film” Sparrow on the Sea at the M+ Museum, and stills from the film are included in this exhibition. Sparrow on the Sea, inspired by classical character forms, captures the graceful moment when a bird prepares to take flight over the sea, metaphorically evoking the courage of an individual in pursuit of the beautiful. The film draws on visual elements from classic Hong Kong cinema of the 1970s–1990s, with the camera lingering between seaside villages and nocturnal urban landscapes. Its black-and-white imagery oscillates between reality and fiction, between historical memory and the future. Interestingly, the spiral staircase depicted in the stills echoes the spiraling staircases of Candida Höfer, reminding us that in history or aesthetics, whether moving forward or backward, the path often traces a similar arcing spiral.

Curated by Shi Hantao, the special exhibition themed The Fleeting Light and Shade invites director Jia Zhangke and his artist collaborators to engage in dialogue through moving-image works. Jia Zhangke’s Tattoo Series is shown alongside Yu Lik-wai’s Big Happy Series, created in close collaboration with the director. Thai artist and filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s works often explore themes of memory, loss, identity, desire, and history. Signs and Illusions presents the reverse side of a massive sign photographed in a sign-making factory. The white dots on the upper layer of the image are the sprocket holes used in the film Memory to mark the start and end positions; the artist scanned these perforations and overlaid them onto the photograph.

On site, Oui Art encountered emerging artist Lean Lui, born in 1998, presented by PETITREE Gallery. Her Girls Town series constructs a visual allegory, capturing the condition of women navigating from crisis to turning points, while using the European-style architectural backdrops of the city to subtly reflect the inner preconceptions and scrutiny of the external world during youth.

In an interview, she remarked, “The youthful body occupies urban space in a disorderly manner, as if also conveying a will to dominate.”

The “town” of the girls is not a refuge, but an exposed vessel.

“In the spectacle, the passage of time is crystallized into an exhibition that never ends, each second peddling illusions of the future.”Guy Debord, in The Society of the Spectacle, argued that the spectacle objectifies and controls human life: “Life itself presents as a vast accumulation of spectacles. Everything that directly exists is transformed into an image.”Reflections by photographers on the texture of cities and the traces of human exploration may, perhaps, allow us this early summer to revisit urban spaces through the lens of individual experience, rediscovering the pleasures of daily life and the aesthetic resonance they offer.

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Editor:Tiffany Liu

Photographer:Oscar

Designer:Nina

Image: From the 10th Shanghai Image Art Expo

(PHOTOFAIRS Shanghai)