I deliberately omitted linguistic elements within the exhibition space, so as not to disrupt the dialogue between the sculptures and their surroundings. I do not embrace the notion of “total art,” for I wish the audience to remain conscious that they are beholding a work of art. Recognizing that this piece is the creation of a single individual can guide viewers to reflect upon the social conditions and the fabric of everyday life.

— Geof Oppenheimer

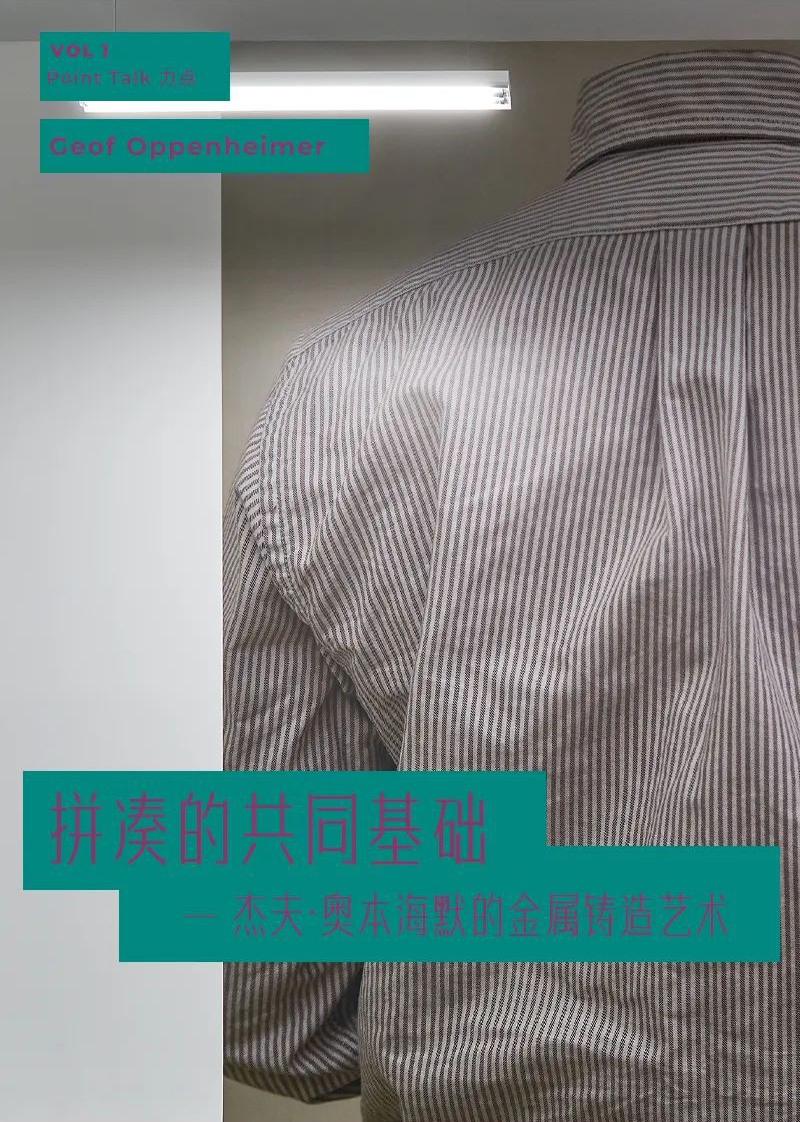

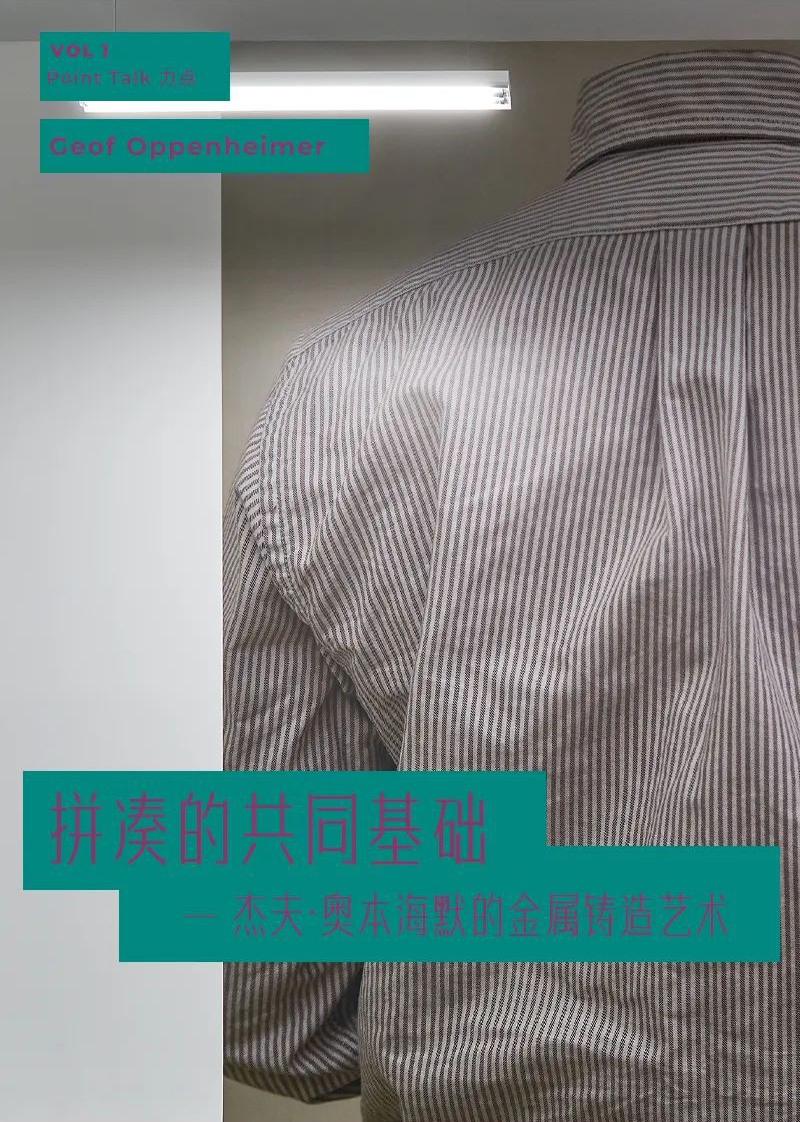

At first glance, the works of Geof Oppenheimer appear rooted in the metal-casting traditions of the nineteenth century, a lineage reinforced by his own formal training in metal casting. Yet, while much of his oeuvre is rendered in metal, he occasionally embraces a multiplicity of materials and techniques. These sculptures carry a hint of Rodin’s sensibility; though constructed from assemblages of materials, the final forms are invariably complete and disciplined. This quasi-ascetic pursuit of aesthetic rigor has become a distinctive hallmark of his practice. At the heart of Oppenheimer’s artistic philosophy lies the concept of “value”—a notion that resonates simultaneously in economic, sociological, and symbolic registers, probing how the significance of symbols might be restored within contemporary art. Often composed of composite objects, many of Oppenheimer’s sculptures investigate the erosion of shared stances within public discourse, and through the medium of metal casting, they are transfigured into forms of enduring resonance.

1. People in Reverse

At Beijing’s UCCA exhibition People in Reverse, Oppenheimer presented only three sculptures cast in bronze and aluminum, which he termed “characters”: the Observer, the Standard-Bearer, and the Merchant. In certain areas, these sculptures are bound, as if tending to or repairing some wound, reflecting how each of us finds ourselves only partially situated within social relations. After World War II, we were left with a relatively binary system; yet within a system increasingly characterized by fluidity and easily exchanged resources—commonly referred to as neoliberalism—Oppenheimer suggests that we have arrived at a pivotal moment, entering a new system whose entirety remains beyond our comprehension. The resulting sculptures depict figures uncertain of their future, each character bearing distinct past experiences. To embody this transition, the three sculptures in the exhibition are constructed from different, sometimes irreconcilable pasts, giving form to an unknown future.

OUIART :

Why did you title your exhibition People in Reverse?

Geof Oppenheimer:

I titled my exhibition People in Reverse because I employ various types of metal in casting the sculptures, a process that involves the technique of reverse casting—creating a mold of the object before finally producing its cast form.

OUIART :

Since 2019, this project has evolved over three years. How has it transformed over time?

Geof Oppenheimer:

This long-term project has been immensely challenging, particularly against the backdrop of the pandemic and social upheavals. Over time, the environments surrounding the three “characters” have grown increasingly complex—the settings originally envisioned for the three sculptures in 2019 have evolved, becoming as significant as the sculptures themselves.

2. The Characters

Oppenheimer believes that art can probe and respond to questions of community and value, extending beyond mere aesthetics. The exhibition People in Reverse itself functions as an installation space, segmented into multiple directions, presenting the audience with the challenge of navigating an abundance of possible paths and lines of inquiry. The installation resembles an immersive theatrical stage, where viewers encounter a series of scenes and characters as they move through the partitioned space.

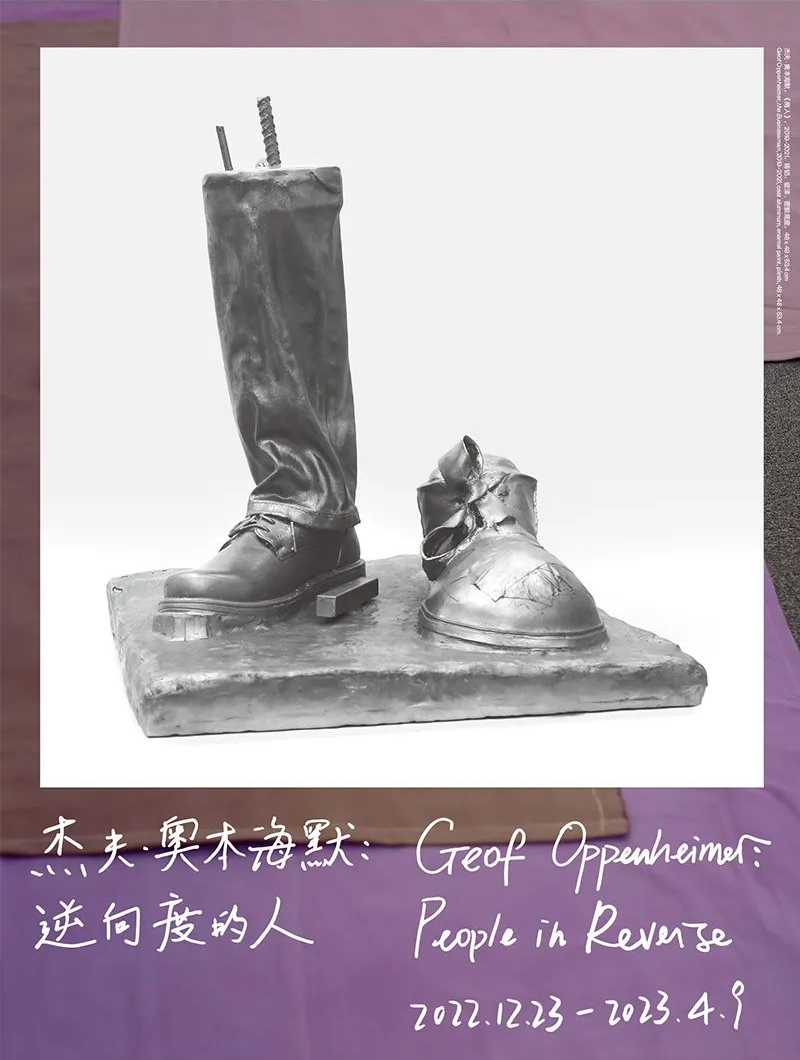

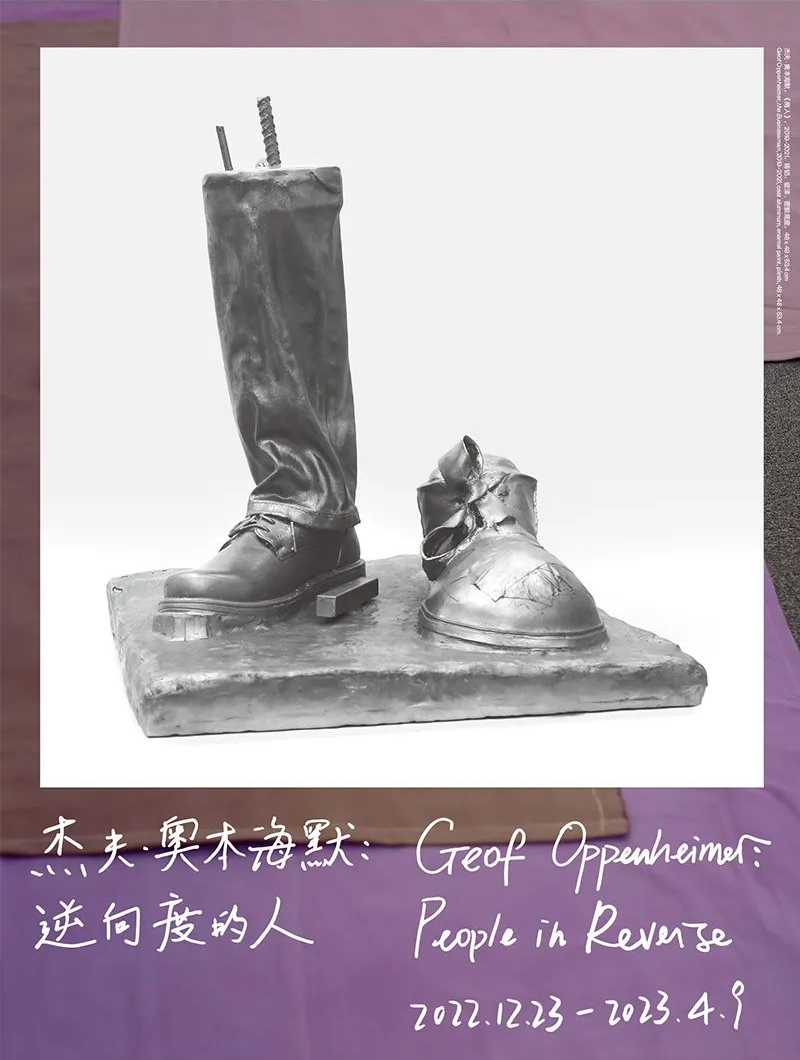

The Businessman stands alone, positioned atop a base crafted from Formica. The figure assumes a heroic stance: one foot firmly planted forward, perpendicular to the base, while the other leans backward. The placement of the feet alludes to the contrapposto of Western sculptural tradition, a pose that once infused classical ideal statues and monumental sculpture with vitality. Yet in The Businessman, only the suggestion of contrapposto remains, compelling viewers to reconstruct the posture from partial evidence at the feet. The figure is composed of a series of ready-made objects, joined and cast in metal. The original items are often destroyed during the casting process, yet their specters persist, traceable within the final cast form.

The sculpture centered on a flagpole is The Flagbearer, its metal surface left blank, devoid of any specific pattern or color. This deliberate absence of specificity erases any unique identity associated with the flag, rendering it universal and meaningless. Oppenheimer’s intention is to highlight the fragility and instability of symbolic forms, as well as their capacity to retain meaning over time. By creating a blank canvas, he questions our trust in symbols and the assumption of their permanence. The Flagbearer embodies the failure of symbolic meaning, reminding viewers of the fluidity of language and the power inherent in interpretation.

The third character, The Observer, takes the form of a life-sized bronze glove, holding a magnifying glass aimed at a blank tablet. The tablet is cast with a monochrome surface, displaying no text, prohibition, or guidance. Positioned atop a laboratory cart, the sculpture evokes a scientific context, yet even when viewers peer through the magnifying glass, nothing is revealed. The Observer questions the notion that surveillance and scrutiny can yield deeper understanding, suggesting instead that continual observation may exist for its own sake, offering no real insight. This sculpture invites audience interaction, yet the hope of revelation through looking is denied. Like Oppenheimer’s other figures in the exhibition, it demonstrates, through the depth of absence, the fragility of symbols.

OUIART :

Why did you choose not to display explanatory texts or written materials within the exhibition space? The experience of the exhibition seems to merge with the experience of the works themselves—does this relate to the notion of a “total artwork”?

Geof Oppenheimer:

I deliberately omitted linguistic elements within the exhibition space, so as not to disrupt the dialogue between the sculptures and their surroundings. I do not embrace the notion of “total art,” for I wish the audience to remain conscious that they are beholding a work of art. Recognizing that this piece is the creation of a single individual can guide viewers to reflect upon the social conditions and the fabric of everyday life.

OUIART :

You often work with ready-made objects, yet the sculptures are always presented as unified entities, despite being composed of disparate elements. How do the autonomy of the sculpture and the importance of handcrafting influence your process?

Geof Oppenheimer:

For me, presenting a sculpture as a unified entity, even when composed of disparate objects, is of paramount importance. This aesthetic approach derives from nineteenth-century casting methods, which I have consistently employed in my studio practice. References to handcrafting are crucial to my process, for it is through these singular cast objects that the autonomy of form is realized. I aim for my sculptures to offer viewers a self-contained form or character, inviting them to explore its social significance and the conditions of society.

OUIART :

Do your works embody specific masculine traits, given the traditionally male-associated symbols, such as the businessman’s boots?

Geof Oppenheimer:

While I have not specifically focused on presenting masculinity in my artwork, as a man living in the United States, I am aware of discussions surrounding toxic masculinity. At the same time, I consider it important to explore new definitions of the male image. In my past work, such as Twentieth Century Hustlers, I have examined these ideas in detail, investigating the multifaceted nature of masculinity.

3. Monuments and Public Arcades

Oppenheimer is intrigued by the function and material presence of monuments, which endows his sculptures with a lingering aura, as if they perpetually hover between remembering what is lost and never forgetting. He investigates the roles of weight and traditional value within the modern economy, raising questions about the shaping of bodies and figures, the positioning of monuments, masculinity, and how sculpture adapts to the emerging systems we are entering. Of course, the sculptor does not claim to have all the answers, but these are the questions that continually inform his artistic practice.

The artist also draws inspiration from De Chirico and the metaphysical approach to space he championed. For Oppenheimer, De Chirico is not a surrealist; unlike the more flamboyant surrealists, his work possesses a hardness that appeals to a sculptor. Notably, De Chirico addresses the isolation of the body within public space, concentrating all energy on the figures inhabiting that space. Within the exhibition, the artist similarly “borrows” the concept of arches from public architecture—a form common across many cultures—thereby transforming the site into a space where political discourse can unfold.

Accompanying the various sculptures, the exhibition includes a series of photographs that explore the history of material and value. Among them is an image of the world’s oldest mine, drawn from a composite of a 14th-century Bavarian wood carving, serving as an allegory of debt. In addition, there are photographs of Microsoft’s headquarters in Redmond, Washington, which Oppenheimer sees as emblematic: the building that gave rise to Windows 84 signifies the end of a material-based economy and the opening of a new era defined by uncertainty.

OUIART :

Could you explain your references to De Chirico and the purple carpet on the floor?

Geof Oppenheimer:

I am particularly drawn to the melancholic arches, figures, and romantic atmosphere in De Chirico’s paintings. They evoke for me a hot summer evening, when sunlight casts long shadows. I cherish that moment, and it is clear that De Chirico did as well, as seen in the arches within his spaces. My focus is on his forms, entirely devoid of conceptual elements. The purple carpet on the floor was chosen to introduce a vivid element that stands out within the space.

OUIART :

How do you see the relationship between the photographs and sculptures in the exhibition?

Geof Oppenheimer:

The photographs serve as one layer of the exhibition’s backdrop, shaping the overall atmosphere and reflecting relationships among concepts such as capital, obligation, and value, while resonating with the materials used in the sculptures. Each photograph represents distinct social relations—for instance, the world’s earliest mine, Microsoft’s office where the Internet was first developed, and a 14th-century Bavarian sculpture exploring the interplay of debt, capital, and obligation. Together, these elements create a more integrated exhibition space, engaging with the complexities of modern society.

4. Politics and Emotion

The Businessman was conceived by Oppenheimer as a failed monument or sculpture, its exposed rebar evoking a sense of poignancy. His work employs allegory and metaphor centered on revealed structures, prompting reflection on architectural and design elements that are typically overlooked—much like the scaffolding and reinforced concrete in a sculpture that might, at first glance, appear hazardous. The scattered rebar may seem random, yet it constitutes a crucial component of the piece. In the artist’s view, as political philosophers Martha Nussbaum and William Davis have demonstrated, emotion plays a significant—even decisive—role in contemporary political decision-making. By evoking the emotions tied to public affairs, the artist engages with a critical dimension, fulfilling his own creative mission.

Oppenheimer’s sculpture The Businessman employs rebar as a key element, blurring the boundary between materiality and symbolism, and creating a sense of deconstruction and instability. The rebar, typically used to reinforce concrete structures, is left exposed, competing with the structural supports themselves. This effect of boundary ambiguity positions Oppenheimer’s work as a kind of identification within the social landscape. His style of blurred and overloaded sculpture accurately reflects the contradictions and conflicts present in public discourse, revealing the realities of modern society. Moreover, this approach reflects significant social transformations and the emergence of new symbols that replace old ones, rendering previous symbols meaningless. In this way, Oppenheimer’s sculptures challenge a simplified worldview, offering a thought-provoking and demanding perspective that examines the truths of our current era.

OUIART :

Could you recommend some books that you are currently reading?

Geof Oppenheimer:

William Davis’s Nervous States is an excellent book on the relationships and distinctions between knowledge and information. He is a British author, offering a distinctly British perspective. I have my students read this book in class, and it always sparks interesting discussions. Additionally, I consider Martha Nussbaum to be one of today’s most important political thinkers; her Political Emotions provides an insightful summary of the interplay between reason and instinct.

OUIART :

Your work often addresses social relationships. How do you approach the term Relational Aesthetics?

Geof Oppenheimer:

When I attended art school, Relational Aesthetics was a popular concept, but it is not how I approach art. I focus more on social behaviors than on methodology. Relational Aesthetics is a method, tending toward the creation of traditional artworks that embody these behaviors. Marxism also addresses social relations as the distribution of shared resources, but I believe the reality is far more complex, involving questions of who holds power and how people act. Unlike Relational Aesthetics or Marxism, as an artist I am more interested in exploring the less logical and darker aspects of human behavior.

OUIART :

Are the economic and social factors depicted in your work tied to specific periods in the United States, or do they relate to more universal human conditions?

Geof Oppenheimer:

Although I am not fond of the term “universal,” I believe my work reflects the human experience of the early twenty-first century. While certain aspects of my work may pertain specifically to the American Midwest, the exhibition’s trajectory—from Saudi Arabia to China to the United States—reflects the global impact of neoliberalism and complex political relationships. Thus, even if my work does not relate to people across all periods, I consider it indicative of broader global human conditions. My work explores economic and social issues faced collectively by humanity, though these issues manifest differently across countries and regions.

Writer:黄格勉

Editor:Simone Chen

Designer:Milkshake

Image provided by UCCA Center for Contemporary Art