The fear of death is a significant driving force in art.

The history of how humans confront the fear of death through art could fill volumes. But when we talk about death, what exactly are we discussing? Artists attempt to use their works to resist this unsolvable fear: Andy Warhol, with his vulgar directness, applied a glamorous filter to car crashes and electric chairs, turning death into a consumable product of modern society; the sadistic Francis Bacon derived a peculiar satisfaction from creating visually shocking experiences; and Damien Hirst, inheriting their legacy, placed death directly in display cases, mercilessly reveling in the audience's shock.

Can art allow people to escape the fear of death?

If we remove terror and stimulation,

remove sorrow and despair,

what might the true essence be?

How is it related to life?

Qin Yifeng, an artist who still fears death,

seeks to explore this question.

01 Starting with a Tree

“It was a tree." Qin Yifeng often begins his introductions to his beloved Ming-style furniture this way. Beyond being an artist, he is the originator of the "plain craftsmanship" concept, a revered figure in the Ming-style furniture circle. Plain craftsmanship refers to Ming-style furniture designs devoid of ornamentation, characterized by simplicity and minimalism, akin to the concept of "less is more."

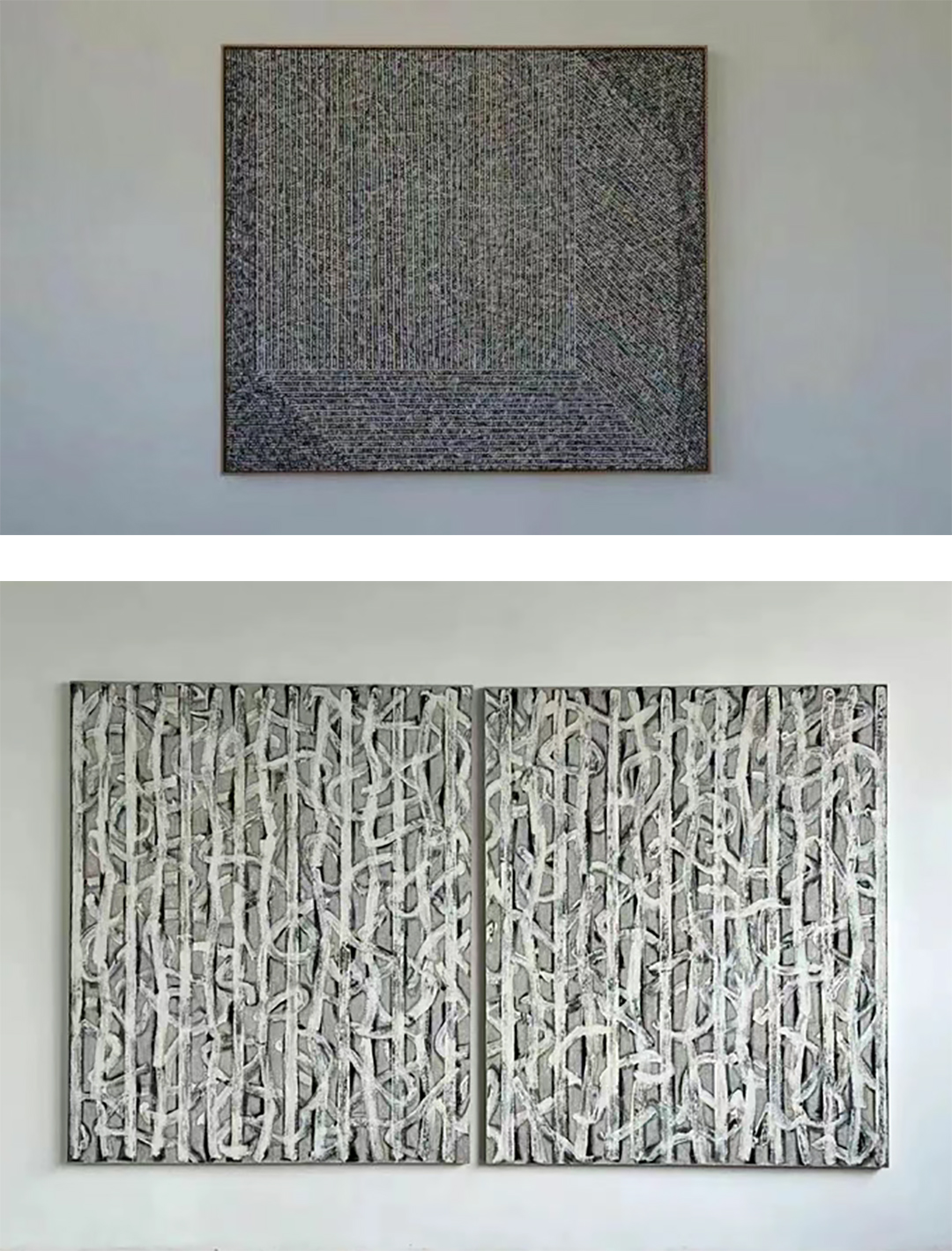

His affinity for this design style can be traced back to his early experiences and abstract works from the 1990s. Graduating from the design department of Shanghai Art & Design Academy, his initial exploration of essence began with the cube. The interplay of geometric cubes, the relationships of existence and opposition, persistently stirred Qin Yifeng's impulse to seek the fundamental. Was this the root? This marked the start of his decades-long journey of "contradiction and opposition"—departing from the cube, the artist distilled two eternally entangled energies into straight lines and curves. These resemble passionate sensibility and cold rationality, or the illusion of impermanence and the solidity of reality. Anyone caught in such contradictions can find their own resonance, reflecting Qin Yifeng's lifelong state of being: a desire to "rebel" while being uncontrollably disciplined. These two opposing forces found visible integration in his abstract art.

The "invisible" integration of these opposing energies, however, occurs in plain craftsmanship. Qin Yifeng often recounts this story: A tree, destined to become a wardrobe or a long table, emits an inaudible scream when felled—it dies. Its "corpse" is meticulously divided into four pieces by Ming craftsmen, with symmetrical planning of patterns and orientation. Not a single inch is wasted, transformed by anonymous, diligent hands into a beautiful wardrobe. Five or six centuries later, it still stands quietly beside us. The tree is gone, but has something remained alive?

This story about the death of a tree contrasts sharply with the work of another artist, Giuseppe Penone, who carved a "tree within a tree" from a centuries-dead cedar, attempting to restore its living form at a certain stage. The fundamental difference between their arts lies in this: the former forces visible forms to perform vitality, while the latter allows vitality to persist invisibly; the former believes human effort can manifest all things, even life, while the latter humbly adheres to rules without overstepping. This reflects the divergent Eastern and Western understandings of life, as different as yin and yang. Yet plain craftsmanship, born from disciplined labor, is like a seemingly finite yet infinitely capacious vessel, compressing energy and charm that can accompany people for centuries. Has the tree truly died? Or is death truly the end? The two opposing energies perpetually entangled in Qin Yifeng seem to find a place to rest in plain craftsmanship's compression of life.

02 Extracting Essence from Objects

In 2009, when Qin Yifeng first pointed his camera at the corner of a plain-crafted table, something significant occurred: through the lens, an image resembling the cubes of 20 years prior emerged. This cyclical return reignited his original question—after stripping away enough "impurities," what remains as the most fundamental essence?

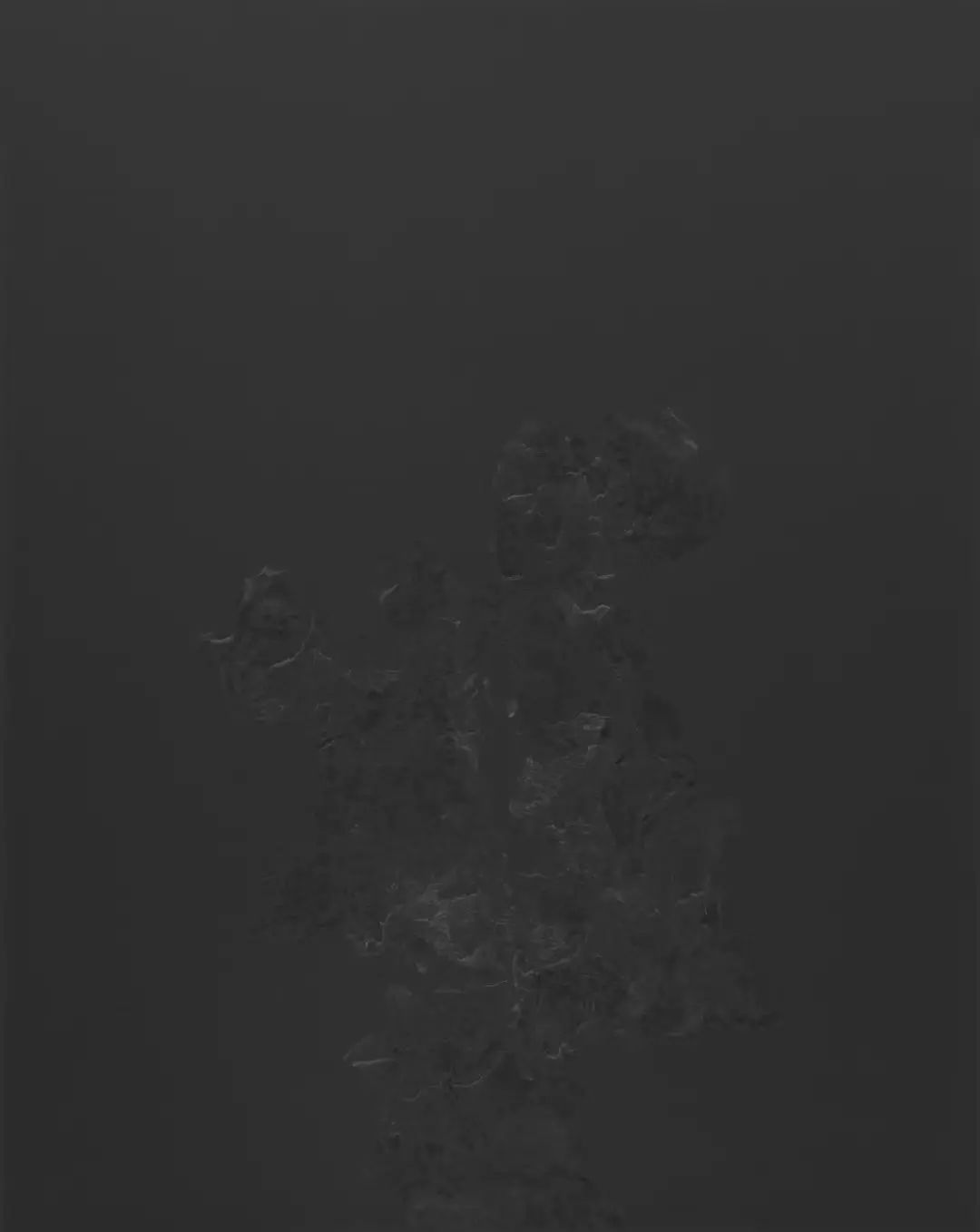

For the next three to four years, Qin Yifeng taught himself photography, capturing over 180 negatives without changing the camera's position until one particular image appeared: perspective, light and shadow, and any illusion of three-dimensionality vanished. The table corner became a "flat" pattern—thus, the Negative series was born. Its strangeness excited Qin Yifeng because the "object" was finally beginning to recede, allowing the obscured essence to surface.

So, what is this essence? Nearly a century ago, another artist pursuing "flatness," Piet Cornelies Mondrian, wrote: "..the universal cannot be expressed purely so long as the particular obstructs the path." Why did he tirelessly paint grids? Because these irreducible elements suited his ideal: constructing ultimate balance and harmony from opposition. This is the artist's task—to approach their goal by continually stripping away distractions. This process of filtration is the true meaning of "abstraction."

Undoubtedly, Qin Yifeng is an abstract artist, engaged in an ever-evolving process of abstraction. Starting from the first stage of "flatness," he increasingly forces objects to detach from their materiality. He renders furniture fragments and withered roses not only flat but also devoid of even a trace of reality or physicality. Any context tied to reality gradually fades. What remains—is it another dimension beyond reality? Once this door is opened, the artist is unsatisfied. Qin Yifeng's recent research focuses on making objects "vanish" under the lens, leaving only a shell on the verge of nirvana. It sounds implausible and difficult, a path the artist must take, fraught with peril and the possibility of failure at every step.

Notably, in Qin Yifeng's photographs, the mystery of objects stems from their own nature. Whether broken branches or fragments, they must confront their essence in decay, emitting a light from within that seems to originate from the depths of the universe. These works remind us that even without the artist's extraction, we can affirm the existence of this solemn light in all things, obscured by transient opulence. Decay, then, is the beginning of its illumination. Why fear loss? In the "negative" world, everything is just beginning.

03 The Eternal Interface

Death is the first unveiling of truth. Qin Yifeng's work assists in the full revelation of this truth. He helps death shed its superficial layers, revealing the indestructible, solid essence beneath—a substance astonishingly dense with energy. Viewers are often misled by a strong sense of "compression," attributing it to the artist's technique, when in fact the artist merely "presents" it as it is. Yet this "compression" leaves Qin Yifeng unsatisfied. To break free from superficial constraints, to further open and release the solid—this is the question he forces himself to answer, closer to his understanding of "death."

"Death is an interface." Qin Yifeng sees death as the interface for the continuation of life's next operation, with the most crucial element being that indestructible "something." It lingers in the faint scent of Ming-style plain-crafted furniture, resides in vivid memories of past lives, and permeates like intangible energy, nourishing not only the body but also influencing spiritual judgments and decisions.

A similar release of this intangible essence can be seen in Felix Gonzalez-Torres's installation Untitled: the artist invites each viewer to take a handful of candy from a pile symbolizing his lover's weight, until the pile, like his lover's passing, disappears. Yet a warm sweetness is released through sharing, transcending the finite nature of the original life relationship. If Gonzalez-Torres's "positive diffusion" is warm, Qin Yifeng's lens captures a "negative diffusion" that is undeniably cold. "There is fear in my work," Qin Yifeng admits, but daily confrontation with and study of this fear dissolve it, even replacing it with the excitement of capturing the ideal image. Even in a decaying shell, facing an uncertain "interface," one can still find a method to explore essence within life's finitude and, through this effort, attain freedom and happiness beyond the physical. As Qin Yifeng says: "I make my own laws. I am my own god."

The gray background in each of Qin Yifeng's Negatives is not directly photographed but modulated by time. As the titles—named after dates and weather—suggest, each image is a slice or screenshot of the object's relationship with time and space. The artist understands the uncertainty of the universe and life, but we can choose how to purify ourselves, allowing the solid to emerge.

Unbound by endpoints, every solid present moment is the interface of eternal freedom.

Q&A with Qin Yifeng

Q: Do you still fear death?

A: Everyone fears death, but death is an interface, an opportunity. Only in death can accounts be settled. Facing my work requires accepting death; each solo exhibition is like a farewell ritual.

Q: Do you never feel anxiety?

A: Fear has always been present in my work. I confront it through repetitive work, and progress dilutes this fear. I don’t feel anxious because the goals are set by me, not society. I make my own laws; I am the god of my own world.

Q: How should artists face criticism?

A: Cézanne wasn’t present at his recent retrospective, so why do people still want to see his work? Why does he have such enduring energy? I often wonder: is the artist truly dead? Art must be as impeccable as Ming-style furniture to endure—do less, but do it thoroughly.

Q: What is your most enjoyable moment?

A: Each evening, reviewing the day’s photographs is a critical moment. The excitement of seeing the results is indescribable. I might have a drink at midnight, no one knows my enjoyment—it means more to me than any exhibition.

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Writer:徐薇

Editor:Tiffany Liu

Photographer:李昊天Rondish

Photography Assistant:正文、小徐

Producer:许伯源

Designer:Nina

Partial image provided by artist Qin Yifeng