Q1:

The exhibition revolves around the theme of the "Elliptical Dipole," presenting life and death as a unified whole rather than opposing extremes. What inspired this perspective of yours? And how did you translate this concept into tangible expressions within your artworks?

A1:

Elliptical dipole motion symbolizes the transformation between polar worlds. It can be seen as a manifestation of the yin-yang cosmology, where one pole transitions into the other—complementary and inseparable. This represents a generative motion of the world, not the opposition of creation and destruction, or material and spiritual.

Unlike the circle, which symbolizes wholeness, the dynamism of dipoles renders the ellipse inherently unstable. I believe this instability is fundamental to our existence. It is a crucial concept in contemporary physics and in philosophy.

This idea originates from the diagram drawn by the protagonist Yuri in the novel Death Studies. The same title was also the subject of my graduation project at music school—a theme that has long resonated deeply with me. Throughout my creative process, I experiment with various materials to explore this ever-changing, generative world. This exhibition showcases many of these experiments and their outcomes.

Q2:

Your work often engages with abstract and philosophical themes such as life, existence, and the cosmos. How do you balance these with audience perception?

A2:

In my work, I continuously explore material imagination as a form of tangible reality. Science reveals realities that often seem like imagination—such as quantum mechanics or dark matter. Meanwhile, virtual physics imagines the unreal, sometimes foreshadowing scientific discoveries. This approach mirrors our modern world, where yesterday's fantasies become today's technologies.

In creating some of my pieces, I employ scientific principles to realize my imagination. When these works encounter viewers, they become embodiments of virtual physics. Imagination transforms into reality, and accepting it as a new world is the essence of virtual physics. You could say each exhibition is a realization of virtual physics.

At its core, both virtual physics and science are tools for exploring the unknown. Their convergence opens new pathways for discovery and creativity.

Q3:

As an interdisciplinary artist, how much time do you spend outside of direct art creation? How do multicultural and cross-disciplinary elements influence your artistic thinking and presentation?

A3:

My inspirations are incredibly diverse. I draw direct or indirect inspiration from literature, music, philosophy, architecture, fashion, mythology, natural sciences, anthropology, and more. But I would say poetry and music inspire me the most. In fact, I wonder if any other art form relates as closely to an artist's life and work as poetry does.

Poetic imagination and emotion are deeply personal, yet they transcend time and culture. Music, as an event composed of sound, is a time-based art that enables us to experience the creation and dissolution of notes as phenomena.

I listen to everything—from the sacred abstractions of Bach to pop music and electronic sound. Especially when developing a new work, I often play one song on repeat—not for the melody, but because it creates a new temporality, transforming my studio into an unfamiliar space.

Q4:

Your works incorporate many unique and complex materials, such as the luminescent substances derived from algae and explorations of decaying tree fibers in your latest pieces. What informs your selection of these materials and techniques? How do you process and highlight the distinctive qualities and allure of natural materials?

A4:

When I’m fully immersed in working with materials in the studio, I feel like I become part of them. This might reflect the East Asian way of thinking about the relationship between humans and nature. In East Asian thought, to truly understand a tree, you must become the tree.Similarly, while working with materials, one forgets the self and merges with the matter. Painters or sculptors may share this sense of union. The French philosopher Gaston Bachelard used the four elements—fire, water, air, and earth—to articulate “material imagination.” His writing, particularly on the materiality embedded in poetry and literature, continues to fascinate me.

Q5:

Have any writers or artists significantly influenced your current creative direction?

A5:

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha had a profound impact on me when I first arrived in Germany. Reading her work Dictée, I realized how easy it is to command others but how difficult it is to command oneself. This book holds great significance in postcolonial feminism. As an Asian student navigating European art, culture, and philosophy, it became a pivotal reference—giving meaning to my anxieties, thoughts, and even my identity.At that time, I was able to move beyond the world of language and delve deeper into materiality and its essence. I would describe it as a latent materiality beneath linguistic structures.

Q6:

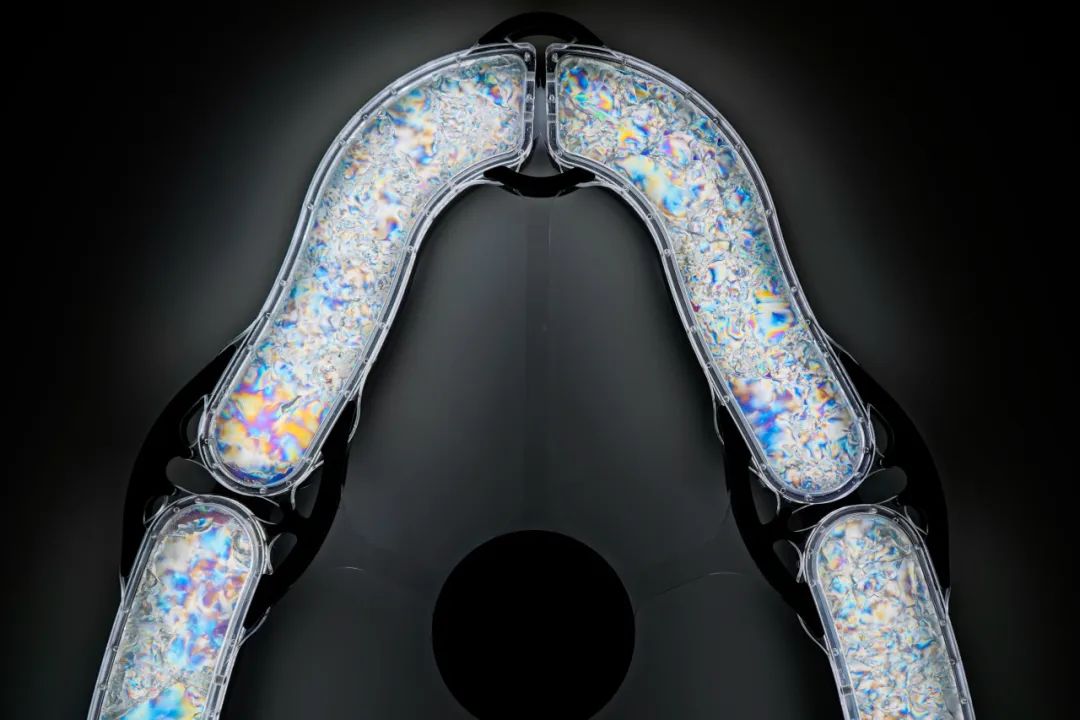

In the Chroma series, recent works seem to adopt animal-like forms, paying homage to poetry or mythology. Could you share the thoughts and intentions behind this? What inspired the newest piece?

A6:

The form was actually generated from a mathematical equation and realized physically. While many interpret it as a serpent or dragon, the work began from an abstract knot. That is precisely what makes it beautiful—you are free to imagine it as you wish.

Q7:

Chroma IX holds mysteries. From afar, it appears as a large-scale installation, but upon closer inspection, it reveals itself as a flexible, shimmering kinetic piece. The mechanical "breathing" effect is astonishing—even the occasional drop of oil on the floor feels intentional. Your on-site remark about it resembling "bodily fluids" was striking. It’s as though everything is alive. Was this your intention?

A7:

I view my artworks as living entities—akin to the resurrectedlike the resurrected “performers” in Raymond Roussel’s surrealist novel Locus Solus, possessing what Karen Barad terms "intra-activity" and self-organizing bodies.The exhibition space becomes a labyrinthine reflection of our decentralized world—a world of entangled existences.

My installations are born from months of rigorous experimentation with materials until they are imbued with life. Their roots lie in my drawings. I often dream of strange beings and rotating forms, which I sketch. All my installations reference earlier drawings—some even tracing back to a sketch of a maze filled with lion-flowers, serpents, and flame-like fluids from a dream I had over a decade ago.

This exhibition invites viewers into a material world where objects, lifeforms, and nature coexist equally—envisioning a flat ontology.

Q8:

Earlier works like Hello, World! explored interaction between artwork and viewer. More recent pieces like Swollen Suns and Chroma IX explore interactions between artworks. How has your understanding of interaction evolved?

A8:

In my work, the material world is paramount—things interact with their environments. When people view art, they often focus on form, size, or surface—not the material itself. Art history tends to prioritize socio-cultural context over materiality, though it is materials that define what can be done, and how.

For instance, architectural forms vary drastically based on materials like ice or brick, not to mention environmental factors like weather. Materials are always connected to their surroundings, including gravity.

Q9:

Remnant Vitrine is structured like a "museum," offering glimpses into your creative experiments. Why this approach? How do you hope viewers interpret it?

A9:

Creating Remnant Vitrine allowed me to examine the origins of materials and the myriad inspirations behind my work: experimental results, sketches, natural specimens, and books. While technology, science, and ideas progress endlessly, natural materials—dried or discolored by environmental shifts—serve as conduits to myth, culture, and history.

The cabinet comprises 12 vitrines with six drawers each, grouped into ten categories: Earth Elements, Liquified Imagination, Kinetic Pulses, Fluid Forces, Microfluidics, Mathematical Mechanics, Electronic Materiality, Cosmic Elements, Imaginary Geographies, and Elemental Residues. I’m currently compiling them into a booklet. It’s a cabinet of unrealized potential—a portal of imagination and space for the residues that sparked my inspirations.

Q10:

Your works exude energy, dialogue, chaos, and a sense of fate. Yet in person, you appear methodical—almost like an ancient "Doctor Strange." Does this contrast stem from your personality or life experiences?

A10:

(Laughs) During my Venice exhibition, many viewers called me "Doctor Strange." While my thoughts may scatter, working with physical materials demands a state of static time—a meditative focus to comprehend and engage with the world. Without this, I couldn’t control or realize anything. This is where scientific methodology and artistic theory overlap.

While my personal inclinations influence my work, it’s the materials’ tendencies that truly drive the creative process.

Q11:

Music composition is one of the most abstract art forms. How has electronic music influenced you?

A11:

Music was my first language and remains a primary source of inspiration. Studying contemporary composition involves thinking about music through other disciplines—natural sciences like math, physics, and astronomy; humanities like philosophy and aesthetics; and fields like architecture and art.

Historical figures like Pythagoras in Greece and Confucius in China explored tuning systems, bridging music with broader knowledge. I collaborate more with scientists than artists, believing that multiple perspectives on a single subject—say, infinity—yield richer, unexpected depths.This interdisciplinary practice allows me to move freely among materials, machinery, sound, and beyond.

Q12:

Has your worldview evolved with age? How do you see yourself in relation to the cosmos now, especially in a post-anthropocentric context?

A12:

Studying ancient Chinese paintings, I’m struck by artists’ profound understanding of nature. While Western education highlights figures like da Vinci, Chinese painters observed bamboo shoots to capture their essence in a single brushstroke—merging natural insight with artistry.East Asia has long embraced an eco-centric worldview, unlike the West’s anthropocentrism. Modern philosophies emphasizing non-human agency echo classical Eastern thought. Though educated in the West, these roots remain ingrained in me.

Q13:

What experiences trigger your "affection"? Is it materials, colors, encounters, or journeys and spaces?

A13:

"Affection" is vital in my work. When viewers engage with my fluid-based pieces, their bodily responses precede emotional reactions. The mechanical movements of my installations share spacetime with their bodies—it’s about experiential encounter, not interpretation.

Q14:

How was your collaboration with 798CUBE? We know its focus lies at the intersection of technology and art.

A14:

It was a wonderful experience. As an artist, imagining my works inside such a unique and beautiful space was immensely inspiring. I’m deeply grateful to the CUBE team for their passion and professionalism. Their support extended beyond the physical space—it was a true collaboration.

Q15:

Could you share a song and a poem with our readers, resonating with this grand exhibition in China?

A15:

Evanescence plays on loop through wall-mounted speakers—the sole sonic interior of the exhibition. A poetic fragment on the end wall offers a glimpse into my creative process and the quiet thoughts behind the works.