This is a story of geniuses wounding each other. If the world misunderstands artists, it is often through these two stereotypes:One is the fragile "madman," lacking the maturity to navigate society smoothly;The other is the aloof "hermit," constantly seeking a utopia to escape from the world. If there is a commonality between them, it is their relentless resistance to the mundane world. The protagonists of this article, Van Gogh and Gauguin, are two such famous artists who fit the archetypes of the "madman" and the "hermit." Between these two artists lies a famous story—after living together for 62 days, the incident of Van Gogh cutting off his ear occurred, which directly led to the end of their relationship. Nineteen months later, Van Gogh shot himself, and the two never saw each other again before his death.

This is not a suspenseful gossip piece aimed at unraveling the causes of the incident. Regarding this famous legend in art history, the part that always piques our curiosity is: Why are there incompatible elements between great works of art? Between great works of art, is there an invisible hierarchy and structure?

Artistic questions must ultimately be answered through art itself. Let us attempt to find answers in the works created by Van Gogh and Gauguin during their 62 days together.

1. Jean Valjean vs. The Japanese Monk: Two Outsiders

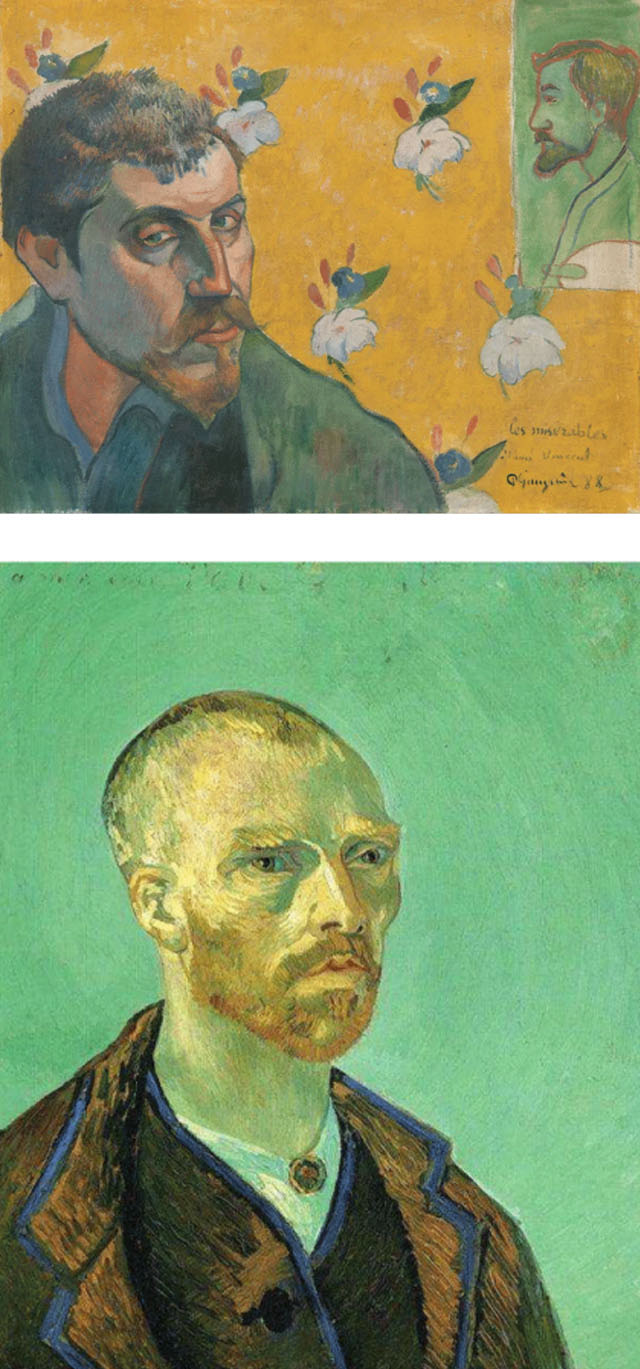

The story begins with the self-portraits of the two artists.

Before Gauguin arrived in Arles at Van Gogh's invitation, the two had been corresponding frequently. Van Gogh eagerly anticipated Gauguin's arrival because Gauguin's eloquence and confidence were immensely charming to the shy Van Gogh, exuding a leader-like charisma. Before Gauguin officially set off, Van Gogh proposed exchanging self-portraits, thus lifting the curtain on the story:A 35-year-old Dutchman and a 40-year-old Frenchman, both artists who only picked up the brush in middle age, sent each other slightly distorted yet idealized self-portraits. Perhaps we can glimpse the secrets hidden deep in their souls.

In the lower right corner, Gauguin inscribed 'Les Misérables,' a reference to Victor Hugo’s novel about a convict,This is how Gauguin saw himself—an exile, a martyr, but also a saint. In his letters to Van Gogh, Gauguin even repeatedly emphasized: "The contours of his face, as resolute as those of Jean Valjean, reveal, beneath worn clothes, an inner nobility and gentleness... This speaks to passionate painters like us!" This proud temperament of Gauguin's was keenly captured by Somerset Maugham, and the "criminal-like" aura of the protagonist Strickland in The Moon and Sixpence was modeled after Gauguin.

Compared to Gauguin's self-comparison to "Jean Valjean," Van Gogh's self-identification was more religious:A Japanese monk. In his letter to Gauguin, he described it this way:“ I wanted, while working, to make myself a monk, a monk who worships the eternal law." In the treatment of the image, he even painted his eyes as more Asian-like, with upturned single eyelids, his expression and posture tense and silent. A faint pinkish-green radiated from the top of his head, as if enveloped by a mysterious, cool halo.

One was a wild seeker of freedom, a criminal; the other was a monk practicing compassion. Their commonality was their skepticism and resistance toward modern civilization, but their vast differences were also laid bare in their paintings: Gauguin was a heretic filled with opposition and resentment, while Van Gogh was a preacher radiating light. The former believed that only by completely escaping modern civilization could one find a pure land, while the latter believed that paradise might exist in every corner of the ordinary world. These differences are even more evident in their representative works.

Gauguin tirelessly depicted his envisioned utopia: a primitive society far from the hustle and bustle, where people lived in harmony with nature, their vitality simple and robust. This obsession with the primitive was built upon a strong critique of modern civilization. If happiness existed, it lay in returning to the lost paradise—a denial or escape from reality. Gauguin was always rebellious, yet always innocent and full of strength.

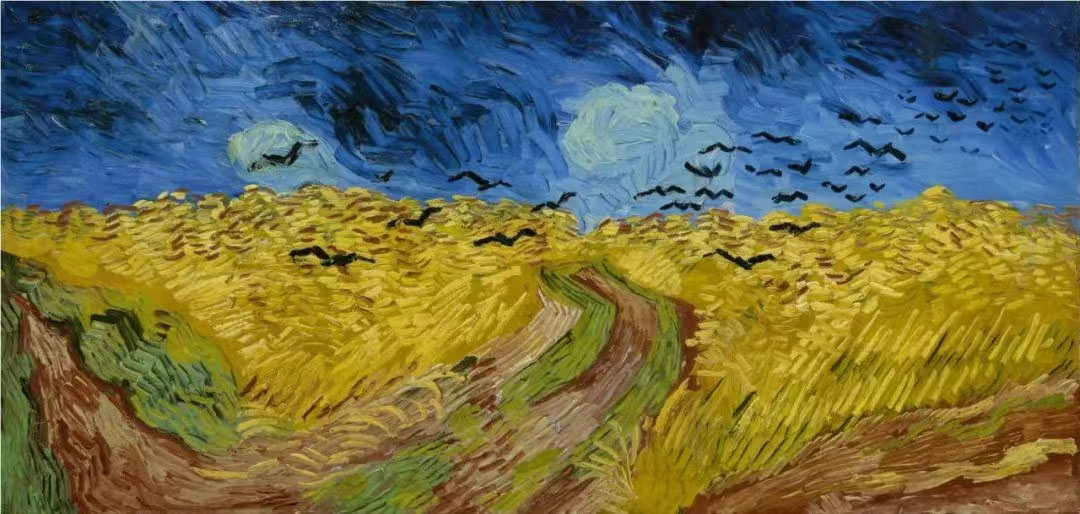

In Van Gogh's paintings, we see that even the most ordinary farmers can bask in a compassionate light. Their hard work reveals the inherent dignity of life, and the sunlight at that moment comforts these simple, humble lives like a divine glow. As Van Gogh wrote to Theo:"It’s something like music, and I want to give men and women something eternal, which the halo of saints used to express, and which we seek to convey by the actual radiance and vibration of our colours." This was Van Gogh's missionary-like perspective of "equality for all," illuminating every corner of the world that deserved solace.

2. Madame Ginoux: Two Visions of Life

In Arles in 1888, many still believed that having one's portrait painted would bring misfortune. Before Gauguin arrived, Van Gogh had only found six people willing to model for him in eight months. But Gauguin's social charm quickly helped them find a new model: Madame Ginoux, the owner of a café.

In Gauguin's eyes, Madame Ginoux was the proprietor of a café symbolizing a turbid and decadent world. The café proprietress slightly tilted her eyes, her lips curled into a meaningful smile, while behind her lay drunken patrons. This was not a sketch from the café but Gauguin's preferred way of integrating characters into a story. Gauguin's artistic world was imaginative and subjective, where characters were grafted into various environments to form a "parable," containing critiques of the world or aspirations for an ideal. Thus, the figures in Gauguin's works often carry a hint of "cartoonish" generalization.

When we look at Van Gogh's L'Arlésienne: Madame Joseph-Michel Ginoux , the first thing we notice is the difference in the positions of the two artists: in Gauguin's painting, Madame Ginoux sits facing the artist directly, while Van Gogh is a subordinate "borrowing" the model, with her gaze avoiding any interaction with him. Although Van Gogh was the master of the studio and Gauguin the guest, Van Gogh clearly occupied a weaker position.

In his depiction of Madame Ginoux, Van Gogh, as always, carefully respected his subject:He completely overlooked her identity as a café owner who dealt with people from all walks of life daily, instead placing her against a bright yellow background—a sacred and stable light. He even placed a few books in front of her, symbolizing the spirituality and dignity he believed even those of lowly status should possess.

In another of Van Gogh's works, Prisoners' Round, his compassion for life is even more evident: even for the most despicable criminals, the artist arranges a "purification ritual"-like recreation. The prisoners are bathed in a pure, kaleidoscopic holy light, as if all human sins could be cleansed and forgiven in this light.

How an artist chooses to depict life not only relates to the scope of art but perhaps also approaches the meaning of art for life: Is art a weapon to critique reality and reconstruct ideals? Or is it a passage to comfort life and transcend suffering?

This is not only the artist's choice but also a question life must answer when facing hardship.

3. Two Chairs: Divergent Dreams

Van Gogh so eagerly anticipated Gauguin's arrival not only because he admired the older artist's talent and charm but also because he pinned his hopes on building a utopian "Studio of the South."

In Van Gogh's vision, his small Yellow House would be filled with like-minded artists, embodying a nearly monastic purity of spirit. But Gauguin had a more business-like plan: he proposed gathering their works together and selling shares to investors, much like a union. Van Gogh was deeply dissatisfied with this. He had hoped Gauguin would become the leader of this utopia and could not bear to see his pure ideal tainted by capital and money. He wrote to Theo, complaining about Gauguin's "Jewish plan."

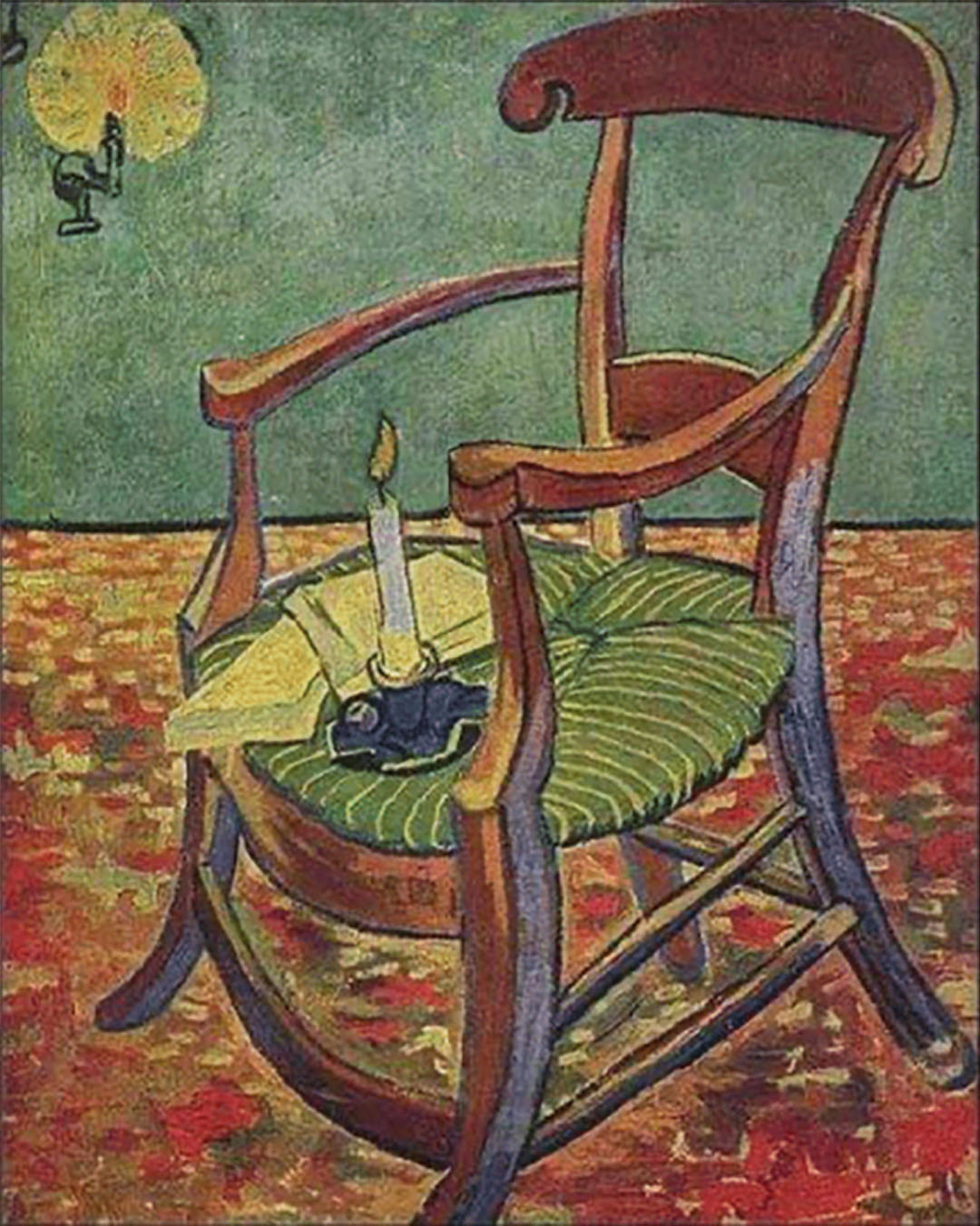

In fact, Gauguin had two purposes for coming to Arles. First, as thanks to Theo, his biggest art dealer, he could not refuse the enthusiastic invitation of Theo's brother, Van Gogh. Second, Arles was a resting place before his next destination, where he could earn enough travel expenses before leaving. In his heart, he may never have truly shared Van Gogh's somewhat naive utopian ideal, and this attitude increasingly agitated Van Gogh. In his fear of Gauguin's departure, Van Gogh painted two empty chairs.

The first was Gauguin's chair. This dark chair had decorative curves and details, exuding a more solemn texture. On the seat cushion were two symbolic items: books representing erudition and spirituality, and a candlestick symbolizing leadership. But the presence of the flame made the chair seem unsuitable for use, emitting a faint signal of danger. When painting this chair, Van Gogh may have already foreseen the end of their relationship.

Compared to Gauguin's ornate chair, the chair Van Gogh chose for himself was the cheapest pinewood chair, yet it exuded an unadorned yet solid character, much like the impoverished masses Van Gogh always focused on, transcending class with its naturalness. On the chair lay a pipe and tobacco, perhaps symbolizing the perpetual sorrow surrounding Van Gogh. In front of Gauguin, Van Gogh was sensitive and insecure, but this insecurity also contained a pine-like hardness and stubbornness.

How did Gauguin see Van Gogh? In The Painter of Sunflowers, Gauguin's portrayal of Van Gogh even incorporated some of his own features, with Van Gogh's body in an unstable state. Van Gogh said of this painting, "It’s really me, extremely tired and charged with electricity after what I’ve just been through." In fact, according to Gauguin's descriptions, Van Gogh in the later stages would sometimes stand anxiously by his bed in the middle of the night, leaving Gauguin deeply unsettled.

In Van Gogh: The Life, there is this passage: “This was a world in which positives were neutralized by negatives; in which praise was diluted by expectation, encouragement undercut by foreboding, and enthusiasm quenched by caution. [...] To this, they were numb and inexperienced, helpless to do anything but watch as their runaway emotions wrecked their lives.”

If Van Gogh symbolized a lofty ideal utterly unprepared for reality, this was his destined fate.

4. Epilogue

On the eve of Christmas in 1888, this brief story reached its climax. In a fit of intense emotion, Van Gogh cut off his own ear. Gauguin immediately fled by train to Paris, not even visiting Van Gogh in the hospital. Today, we cannot uncover the full truth from fragmented records, but a story remains a story. In the works left by these two masters, we see that art never failed a single solitary soul that turned to her with yearning.

Even when gazing at the same sky, everyone has their own perspective. On the path to pursuing lofty ideals, Van Gogh and Gauguin may have shown us a somewhat heartbreaking truth: souls with clearly defined ideals may not need another of their kind. Though souls may seek support in moments of fragility, placing expectations on others often brings more harm.

And all of this is faithfully recorded by art, offering those who reflect the possibility of transcendence.

Editor:Tiffany Liu

Designer:Evans

Partial images: sourced from the internet