At the START Museum,

artists and their works no longer follow linear arrangements,

nor are they defined by themes,

thus gaining the freedom to exist in their own time and as their own monuments.

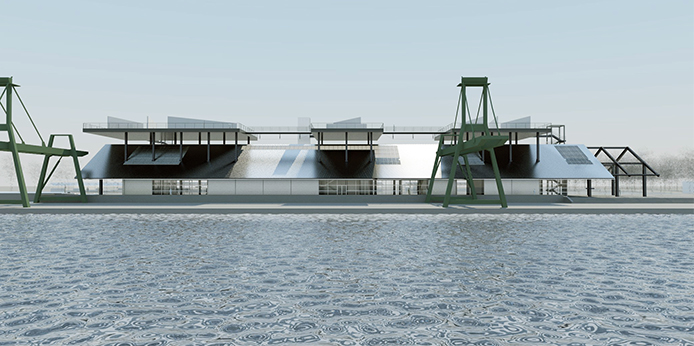

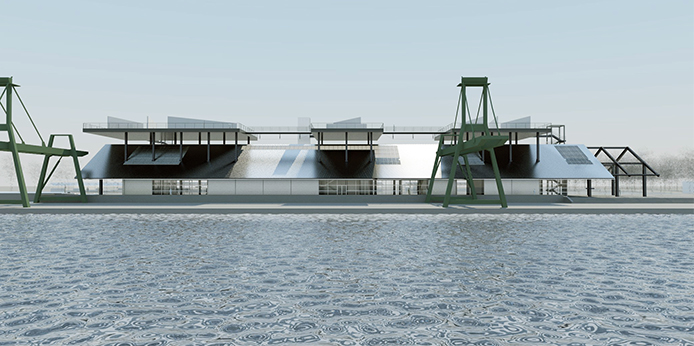

If you stroll along the Xuhui Riverside Greenway, not far south of the Lupu Bridge you will come upon a long, translucent building with a silver-gray sloping roof. Its structure, pure and lucid, recalls the platform of a railway station, or perhaps an industrial warehouse. Above it, three rectangular terraces of differing sizes float in mid-air, standing shoulder to shoulder with the green cranes along the banks of the Huangpu River. Beside the walkway, reeds rise tall, while the feathery white plumes of miscanthus sway in the winter wind, softening the hard edges of steel and concrete. The river is busy with passing vessels, their whistles and engines echoing across the water. Closing one’s eyes, it seems possible to traverse countless spans of time and space: in 1907, during the wave of modernization unleashed by the Hundred Days’ Reform, China’s first rail-to-sea freight platform—the Rihui Port Depot—was completed here; in 1937, after the Japanese army destroyed the original Shanghai South Railway Station, the depot gradually assumed its freight capacity as well as part of its passenger service; following the founding of the People’s Republic, Rihui Port Station was renamed in turn Shanghai South Railway Station and Nanpu Railway Station. This place has borne the aspirations of countless Chinese setting forth across the land, while also driving Shanghai’s rapid transformation. It has witnessed severe environmental degradation, and later the metamorphosis of the industrial ruins along the riverside into the West Bund Cultural Corridor. And now, at the very threshold of this corridor, START Museum—founded by art scholar and contemporary art collector Mr. He Juxing—has at last opened its doors to the public.

Though START Museum, designed by Pritzker Prize laureate Jean Nouvel, is the smallest project undertaken by his practice in Shanghai, it harbors vast ingenuity. The carefully conceived load-bearing system devised by the architects counterbalances horizontal forces, allowing the lofty interior to rise without a single crossbeam—clear in sightline, expansive in floor area. The façade plays in a rhythm of solid and void: broad glass curtain walls dissolve the boundary between inside and out, drawing natural light and river views into the space, while simultaneously offering passersby an open glimpse of the works within, their reflections and presences interwoven. The terraces and skylights are orchestrated with cadence, granting a freedom of light’s entry, as diffused illumination gently shelters the art inside.

At present, the opening exhibition Opening START has unfurled at START Museum, awaiting the arrival of its visitors. Eighty-eight works by eighty-five artists—born between 1921 and 1988, hailing from diverse countries and regions—compose this exhibition, where a multidimensional, multi-perspectival dialogue in contemporary art takes shape. The curatorial team seeks to “reaffirm the spiritual value and contribution of Chinese art within a new historical temporality,” breaking free from the constraints of chronology and thematic categorization, and exploring new points of departure beyond the conventional modes of art-historical writing and the familiar frameworks of popular exhibitions.

For this reason, entering START Museum is like stepping into a game of interpretation, one where “from one angle a range, from another a peak” constantly shifts. Take, for example, Wang Gongxin’s installation Dialogue (1995): the surface of a black desk is replaced by a pool of ink, atop which two light bulbs, controlled by a motor, rise and fall in alternation, casting warm halos upon the white walls while stirring ripples across the serene black mirror of ink. Once the viewer confirms that the ink will not overflow, a sense of calm arises from the rhythmic alternation. Not far away, Nam June Paik’s seminal work Candle TV (1991) similarly draws one into contemplation through light. Ink, white candles, Zen—these works may be understood within an East Asian cultural context, yet this is not the only lens; one may also observe the motors in action, the disassembled television casing, and, in gazing at the light, enter into a dialogue with oneself.

Moving further along, Chen Zhen’s Human Pagoda《人类之塔》 (1999), constructed from colored candles and an array of chairs, depicts a closely interwoven, mutually supportive vision of multicultural coexistence. Though its palette resonates with the 3.66-meter-diameter circular spinning painting by Damien Hirst across the gallery, the juxtaposition reveals two entirely distinct modes of creation and worldviews. Both artists work with a childlike spirit: Chen Zhen assembles as if stacking building blocks, while Hirst employs techniques reminiscent of children’s painting lessons seen on television. Chen’s handcrafted candle tower leans and wobbles, almost laborious and unpolished; Hirst, by contrast, flings paint onto a motorized rotating canvas, presenting the result as a seemingly decorative work.

Chen’s candle tower carries forward the enduring humanistic concern of his practice—innocent, steadfast, sincere—whereas the spinning canvas continues Hirst’s conceptual play with art history, bearing the provocative title Beautiful, Cheap, Low, Easy, Anyone Can Do It, Big, Motorized, Spinning, Heaven, Rotten, Junk, Bad Art, Shit, Exciting, Attractive, On the Couch, Celebrating Painting (1996).

Moving through START Museum, the intricate threads linking disparate works reveal themselves at every turn. Facing Xiao Feng and Song Ren’s Bethune (1973–1974) is Zeng Fanzhi’s Warrior (2004), juxtaposing the searing reality of conflict with romantic imagination, offering divergent definitions of heroism. On the mezzanine, after viewing Zhang Hui’s eight blue safety helmets in Blue Print - Gathering (2014) , a glance down reveals Fang Lijun’s golden crown in 2008.8 (2008), composed of fruits, flowers, branches, and jewels. Ding Yi’s Appearance of Crosses 2020-1 (2020) and Zhang Enli’s Temporary Space (2013) occupy opposite corners, gazing toward each other. Some works, however, can only be fully apprehended in the physical exhibition space. At START Museum, viewers may observe Shi Hui’s Compendium of Materia Medica No. 1 (2011), crafted from pulp and herbs, appreciating its materiality, organic simplicity, and enduring handcrafted tradition; or delight in the shimmering rhinestones of Mickalene Thomas’s Naomi Looking Forward (2013), smiling at the woman’s backward glance, the Black figure emerging from the background to the center, and the playful embrace of “bad taste.”

All of the above is but a glimpse through a narrow tube. Yet what considerations underlie the curatorial logic of "non-linear, de-thematic”? What stories unfolded during the eight-year preparation of START Museum? In early January 2023, OUIART visited No. 111 Ruining Road for an in-depth interview with Mr. He Juxing, director of START Museum, and art scholar. From his tenure as director of the Yan Huang Art Museum in Beijing, to leading the creation of Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum, overseeing the planning of Beijing Minsheng Art Museum, and ultimately the opening of START Museum, he shared forty years of insight into the paths of art collecting and cultural research.

Q1

OUIART:

How did your initial encounter with art come about? Could you share with us the story of the very first artwork you collected?

He Juxing:

I’ve loved reading since childhood. My father and five generations before him were educators, and my elder brother also taught in our hometown (Zhuji, Zhejiang). He often brought back books—Russian literature, Chinese classics—and I read them all. My mother once told me about her early days after marrying into my father’s family: there were seven boxes of scroll paintings at home, but due to historical reasons, they were all burned, leaving only seven empty boxes.

At 14, I published my first short piece in Qiantang River Review (钱江潮评), a column in Zhejiang Daily. The article was tiny, and the fee was small—about 1.5 yuan—but it was my first earnings as a writer, which greatly encouraged me. Later, I joined the military and studied journalism at Nanjing Army College, then Chinese literature at East China Normal University. When I first arrived in Shanghai at 18, I was struck by its beauty and thought: How lucky I am to be in such a city; I must not waste this fate.

After graduation, I became an officer in the military, earning a salary of 57 yuan—a relatively high amount in the early 1980s. The first painting I ever collected was a work by Li Keran, which I purchased for 600 yuan at the Friendship Store. At that time, the Friendship Store catered to foreign visitors, so it was necessary to first exchange renminbi for vouchers. As a reporter, I often delivered manuscripts to the “The Standard”(文汇报) office on Huqiu Road. After each visit, I would ride my bicycle to the Friendship Store, drawn repeatedly to Li Keran’s painting, which never ceased to captivate me. Eventually, I resolved to spend the considerable sum of 600 yuan to acquire it. Later I learned that a similar Li Keran painting could be purchased for just 200 yuan at Beijing Rongbaozhai; shops selling to foreign visitors tended to charge more. China’s open art market truly began in the early 1990s, so when I bought this work, I had no economic or investment considerations in mind—I was simply moved by the art itself. I was twenty-one years old at the time.

Looking back, I’ve worked in many fields—media, bookstores, banking, and now museums—but my connection to art has never broken. Instead, it’s grown tighter and deeper. What moves me most is that in my twenties (the early 1980s), I encountered an era where spiritual and cultural ideas could be freely proposed and debated, a time that tolerated boundless, even audacious imagination. That era was truly special; it shaped my cultural character and laid the foundation for my relentless pursuit of cultural endeavors. Later, as globalization surged, China assumed a role poised for takeoff. I’ve spent these forty years mainly in Shanghai, Beijing, and Hong Kong, including years abroad for research. These were the best times—if we’re to talk about collecting, I must start with this.

Q2

OUIART:

Your collection includes works by over 400 Chinese and Western artists, with thousands of classic and significant pieces. What threads or focal points guide your acquisitions?

He Juxing:

Early on, work introduced me to many Chinese painters. Though I was only in my twenties, we connected culturally without barriers, and my collection grew gradually. In the first two decades, I acquired important works by Xu Beihong, a significant number by Lu Yanshao, and exceptional pieces by Qi Baishi, Wu Changshuo, Fu Baoshi, Wu Hufan, and other modern masters. After Beijing won the bid for the 2008 Olympics, Chinese contemporary artists stepped onto the international stage. Western collectors and institutions were the first to notice and understand Chinese contemporary art, but I wasn’t far behind—only my perspective differed. They analyzed it through a Western lens, while I approached collecting through the fate of Chinese culture.

Also, perhaps because I was born in the 1960s, my collection often gravitates toward that era. The works in "START" also span from the 1960s to the present—a sixty-year timeframe.

Q3

OUIART:

The construction of START Museum took eight years—what challenges arose during this process?

He Juxing:

Since assembling the team in Hong Kong in 2015, most members have stayed till today. As a non-profit, we can only offer modest salaries, so without passion and shared purpose, such continuity would be impossible. Yet the team remains highly motivated and creative, with exceptional knowledge and research skills, contributing significantly to global contemporary art and Chinese cultural studies. Without their support and confidence, I could never have realized such a grand vision.

Q4

OUIART:

START Museum was designed by the architectural firm JEAN NOUVEL. You once traveled to France to conduct research for this project—could you share with us a few memorable experiences from the design communication process?

He Juxing:

After we initially reached an understanding with the JEAN NOUVEL studio, I flew directly to Paris to discuss the collaboration in person. Our first meeting took place at his home, where I outlined five key points:

1.The museum’s site was originally a train station built in the final dynasty, carrying the Chinese imagination of the industrial age and modern society;

2.During wartime, it had been occupied by invading warships and threatened by bombers, bearing witness to historical turmoil and the resilience of the nation;

3.Regardless of wealth or status, many had dreamed of boarding trains that departed from or arrived at this place, harboring dreams of leaving or returning;

4.The museum sits only a hundred meters from the river, making its natural and cultural environment extraordinarily precious;

5.I hoped to create a museum with an international vision and vibrant creativity.

JEAN NOUVEL’s imagination is remarkable. He was deeply interested in the project and immediately envisioned several possibilities, allowing the collaboration plan to be finalized in this way.

The topic of design fees is unavoidable, especially for a globally renowned master like JEAN NOUVEL. At the time, I told him that my budget would not be large—even a million yuan would represent my personal contribution to the city of Shanghai. This remark moved him. As an artist deeply committed to society and culture, he replied, “I understand. No problem. As an architect, we are not only capable of making expensive buildings; we can also create excellence with minimal resources.”During our conversation, he also shared some of his successful architectural projects and recounted his experiences participating in cultural movements in France during his youth. To me, our youthful experiences were remarkably similar, differing only in era and nationality.

Q5

OUIART:

The START Museum’s opening exhibition is the first of four sequential shows, each lasting five months over two years, featuring over 300 global contemporary artists and 300+ works. The first, "START," presents 88 works by 85 artists. What message does it convey?

He Juxing:

For an art museum, the opening exhibition plays a crucial role in establishing the overall personality and direction of the institution. It also allows visitors to understand the style and demeanor of the museum. In the "START" exhibition, as the curator, we did not set up any dialogue, and the artists and their works were no longer required to follow a linear arrangement or be defined by a specific theme. They gained the freedom to create their own time and establish a monument.

We all know that one of the most common ways to organize art today—linear narrative—simply dictates who becomes a monument and who a stepping stone. Another prevalent method is to structure exhibitions around specific propositions, which inevitably crushes the individuality of artists, reducing them to components of a theme. Linear sequencing is a trap; thematic framing is a form of stranglehold. Before art, our best role is that of a researcher. From this perspective, we can expand the cultural scope of art and artists in their era, avoiding imposed definitions, arrangements, or thematization. My approach may not be entirely correct, but it is an experiment. The significance of START Museum’s inaugural exhibition lies precisely in this embrace of “non-linear, de-thematic”. Setting aside the personal histories or creative methods of the artists, one notices a commonality in my collection: each work challenges art history—whether by questioning established artistic methods, or by probing the definitions of the artist and of art itself.

Q6

OUIART:

When you first saw the completed "START," was there a particular work or space that moved you deeply? Regarding the present and future of START Museum, what hopes and visions do you hold?

He Juxing:

Yes, I’ve entered this space many times—it’s deeply familiar. From Jean Nouvel’s first sketches, the START Museum, was envisioned as transparent, fluid, and inviting public engagement. Installing massive works without compromising the building’s openness or design is a challenge for any museum, but we strive for it.

The START Museum is a gift I offer to this city. This gift encompasses not only such colossal architectural sculptures, but also my 40 years of research experience in art, as well as various exhibitions with an international perspective that I will contribute in the future. The exhibition hall is free for special groups such as the elderly over 70 years old, children, active-duty military personnel, and people with disabilities. We regard START Museum as an urban center for art education, a place dedicated to cultivating cultural literacy among the public.

In my opinion, Shanghai is the best city of this era. The people in Shanghai have both a gentle and humble side, as well as a proud and self-assured side. They are well-informed and culture holds a prominent position in their hearts. When I was running the Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum, I had a firsthand experience: groups of one hundred visitors would enter the museum in sequence. Even in the height of summer, those waiting in line were remarkably quiet; some read newspapers, and when fatigued, folded them to shield from the sun, then entered the museum when their turn arrived. Such orderliness and civility are rare and precious.I hold deep affection and high expectations for this city, and I trust that both Shanghai and its citizens will feel gratified and proud to have START Museum as part of their cultural landscape.

Editor: Simone Chen

Writer: Saltypink

Photographer, Cameraman, Editing: 罗浩 @HAAALOCOMPANY

Partial images provided: START MUSEUM, MomentStudio

Designer: Milkshake