In Beijing, under a scorching 41 degrees Celsius, I drove from the 798 Art District beyond the East Fourth Ring Road toward the Sound Art Museum near the East Sixth Ring Road. As the navigation indicated we were approaching, I caught sight of the sign for Songzhuang Art District, China rising prominently by the roadside. This urban sub-center of Beijing, past and present home to contemporary art creators, lies just ten kilometers west of Yanjiao in Hebei Province.

Stepping off the car, the cries of summer cicadas shimmered through the sweltering heat. Though it was the Dragon Boat Festival holiday, the vast grounds of the museum saw only a few visitors. After all, this newly opened venue, timed with International Museum Day, and the oppressive temperatures, could easily dissuade those reluctant to undertake a long journey. Yet, once these obstacles were overcome, anyone entering the Sound Art Museum would be captivated by its dazzlingly rich exhibitions and the meticulous, thoughtful curatorial design. Traversing the layered spaces and displays, one cannot help but linger, enveloped in the boundless vistas of the sonic cultural ecosystem that this fertile ground has nurtured and brought to life.

Originating in Tongxian, the road points toward the distant horizon.

More than twenty years ago, an American gallery owner, Jack Tilton, chose Songzhuang as the site to establish an international art center, funding a residency program for artists of global repute. Today, the now-renowned Iranian-American architect Nader Tehrani collaborated with Venezuelan-American architect Monica Ponce de Leon to design the building, originally named the Gatehouse, Tongxian. They conceived it as a monolithic block seemingly formed in a vacuum and instantly compressed into shape, like a sculpture stripped of all excess. Its exterior walls were clad in Flemish brick, creating a texture both solemn and elegant. Completed in 2003, the building has won numerous awards for its innovative departure from conventional architectural typologies.

In 2010, with the construction of Luyuan North Street threatening the Gatehouse, Tongxian, a man named Hong Feng spent six months relocating the building thirty-four meters to the north, preserving this legendary piece of contemporary Beijing suburban architecture. A native of Tongzhou—the very territory of Songzhuang—Hong Feng is one of the principal founders of the Songzhuang Art District and formerly served as deputy director of the Beijing Songzhuang Cultural Cluster Administrative Committee. He has long been committed to nurturing the development of China’s contemporary art ecosystem, founding the China Songzhuang Art Festival and establishing the Beijing Songzhuang Art Development Foundation, the very organization that now oversees the Sound Art Museum.

The relocation of the Gatehouse, Tongxian, once seemed utterly impossible, yet after the move it was given a poetic new name: Ruogu Tower. From this seed, over the past decade, the Huai Guliny Art Garden has gradually grown across 8,200 square meters, with 6,400 square meters devoted to exhibition space. Its scattered buildings now house the various functions of the Sound Art Museum: the permanent exhibition “Sound Terminus”; the temporary exhibition hall “Sound Art Space,” currently presenting Feedback: Sound in Chinese Contemporary Art: 1989–2025; the container complex “Sound Activity Center,” encompassing areas such as Sonic Kids, the Sound Therapy Center, the public education space The Forum, a live music platform, artist residency studios, a pigeon-whistle base, and rooftop gardens, presently hosting the Heaven on Earth sound art exhibition. Additional spaces include the café and bar Fenxiang Bar for small-scale performances, the design and art development hub Fenxiang Creative Design Space, the restaurants Red Purple and Xuhuai Tower, as well as elegant courtyards and groves suitable for outdoor sound installations.

The founding of this novel, cluster-style museum—pioneering in its exclusive focus on sound, that is, on auditory and tactile arts rather than visual arts—relied not only on Hong Feng but also on another co-founder: Colin Siyuan Chinnery. His grandmother was Ling Shuhua (1900–1990), the renowned Republican-era writer of Ancient Melodies (《古韵》). Chinnery participated in the renovation of Ling’s former residence in Beijing, now the Shijia Hutong Museum, where he created a “museum within a museum.” In 2013, he launched the “Old Beijing Sound Project,” popularly known online as the “Sound Museum,” archiving over seventy types of hutong sounds that he had recorded over the years—some of which are now featured in the opening Old Beijing Soundscape section of the Sound Art Museum’s permanent exhibition, Sound Terminus. In 2019, he formally initiated his long-term personal project, Sound Terminus, dedicated to exploring the relationships between sound, society, culture, and memory. By 2020, Chinnery met Hong Feng, and almost immediately they began a dynamic three-year collaboration to establish the Sound Art Museum.

Setting aside his dazzling professional background—graduating in Chinese Language and Civilization from SOAS, University of London, and having held positions at the British Library, the British Council, the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, and the Shanghai Contemporary Art Fair—Colin Siyuan Chinnery is, above all, a fearless experimental sound artist. Ruogu Tower, which is planned to serve as the Sound Archive, currently presents three of Chinnery’s sound art works: Echo Chamber (2022–2023) on the first floor, Chair Sutra (2021) on the second, and Flow (2022) on the third, collectively forming the exhibition Gatehouse Redux—Sound and Concrete.

The Sound Art Museum began internal trial operations in February 2023, and by March 29 it had been officially recognized by the Beijing Municipal Administration of Cultural Heritage as a municipal-level museum. For Colin Siyuan Chinnery, this accreditation serves as a foundation for ensuring the museum’s public character and enabling future collaborations within the broader museum ecosystem. Against the backdrop of Beijing’s initiative to establish a core demonstration zone as a “City of Museums,” the museum confidently contributes rich, on-site cultural content to support the development of Songzhuang as a creative arts town within the cultural tourism industry.

The Sound Art Museum is a non-profit contemporary institution that uses sound as its primary medium, dedicated to the exploration, collection, preservation, and dissemination of sonic works. In order to integrate multiple disciplines and art forms and to establish a sound-centered ecosystem, while nurturing independent and cutting-edge academic and cultural research, the museum also seeks to inspire broader social potential and innovative practice. To this end, Colin Siyuan Chinnery wisely adopted a collaborative “think tank” model. Those contributing to the museum’s content are remarkably diverse—cultural activists, urban historians, architects, scientists, designers, sound recordists, foley artists, programmers, curators, artists, street vendors… even visitors are invited to participate through open calls, genuinely opening up the multiplicity of sound’s possibilities. As a new cultural institution, the Sound Art Museum organically fuses history and contemporary practice, science and art, sound and the senses. Ambitiously, it plans to gradually extend its multilayered, cross-disciplinary exhibitions and sound culture projects through a network of museum collaborations across China and, ultimately, around the world, generating revenue streams to sustainably support the museum’s ongoing development.

A Journey in Color, Giving Form to Sound

As the saying goes, “Seeing is believing.” At the Sound Art Museum, perhaps it should be reversed: “Hearing surpasses seeing.” The immediacy and presence of sound convey subtle yet profound nuances that cannot be fully grasped without direct experience. Within the limits of this text, the following account will guide the reader along a whirlwind tour following the exhibition flow: Sound Terminus – Sound Art Space – Sound Activity Center – Ruogu Tower – the Grove.

Sound Terminus: A Sonic Journey Through Seven Colored Rooms

As mentioned earlier, " Sound Terminus " originates from Chinnery’s 2019 art project, now repurposed as the museum’s permanent exhibition. Seven rooms—gray ("Old Beijing Soundscape"), green ("Nature’s Voices"), cyan ("Speech"), blue ("Music"), white ("Music—Hetian Harmonies"), red ("What Is Sound?"), and black ("Sound and Emotion")—form a dazzling, multidimensional sonic journey.

01 Gray Room: "Old Beijing Soundscape"

This is the first stop for visitors on their exhibition tour. In the open space in the center, there stands a "welcoming tree" leading to the skylight window, named "The Mixed Tree of Beijing". It combines the distinctive features of the most common trees in old Beijing, such as willow trees, persimmon trees, jujube trees, elm trees and crabapple trees. Under the tree, there are small wooden chairs and stools. The changes in weather, from sunny to rainy and from snowy to cloudy, pass through the skylight and through the branches, falling on the visitors beneath the tree.

What reaches the visitors' senses before the trees are the old Beijing sounds that are constantly looping in the space. With 12-channel professional audio equipment, the spatial orientation of the sounds is maximized. The soaring and singing of the pigeon whistles, the calls of candy sellers in the alleys, and the sounds of 40 different scenes throughout the year are continuously filling the ears. Among them are sounds that have already disappeared or are disappearing, such as the sound archives of the Bell and Drum Tower in Beijing. Chinnery said that he and the recording engineer went to record them almost in a rescue mode.

On the four walls of the exhibition hall, the innermost wall continuously projects a black-and-white animated sequence created based on the illustration style of Ling Shuhua's painting Ancient Melodies (《古韵》). The scenes depicted are all scenarios of various sounds heard in old Beijing. The remaining three walls are all museum-quality display cabinets, beautifully presenting various birdcages and pigeon whistles from different schools, as well as the sound instruments used by street vendors for their sales. In the exhibition hall, there is also a stand-shaped cabinet in the shape of a bug jar, inside which are displayed various bug jars used for breeding crickets. Regarding the sound instruments, they refer to various props used by street vendors in conjunction with their sales calls. For example, there are bells hung on the hip bone of a cow, and a pair of brightly colored drumsticks decorated with floral patterns. During the Republic era, street vendor culture was prevalent in Beijing. It is said that as soon as one sits in a quadrangle courtyard, one can hear a wide variety of sales calls: selling food, selling goods, hair salons, fortune-telling, medical services, junk collection... Each trade has its own sales call characteristics. Old Beijing residents can tell what is being sold without hearing the words of the sales calls.

02 Green Room: "Nature’s Voices"

The rhythms and languages of the wild

After traversing a short corridor, still carrying the lingering warmth of old Beijing, you step into a dimly lit room bathed in an eerie green glow. The sliding door automatically closes behind you. At either end of the narrow gallery, screens display the icy blue-white landscapes of Antarctica, immediately cooling the temperature in your heart. The sounds of shifting glaciers, the calls of Adélie penguins, the underwater songs of Weddell seals... This 40-minute soundscape direct from Antarctica forms the inaugural exhibition unit of the museum's collaboration with renowned British nature recordist Chris Watson, presenting natural soundscapes from Earth's seven continents. Watson, who conducted field recordings for the acclaimed BBC documentary series Life with environmentalist David Attenborough, has helped create this immersive experience. Equipped with the same professional custom-designed audio system, the Green Room invites visitors to close their eyes and lose themselves in nature's symphony.

Inside the room, a narrow descending staircase leads to a sound therapy chamber currently reserved for special guests. Outfitted with specialized headphones and comfortable recliners, it creates a fully immersive auditory experience. This space serves as a satellite exhibition area for the " Sound Therapy Center” that will be established in the " Sound Activity Center." Following the official opening of the therapy room on August 5, 2023, the museum plans to gather cutting-edge sound healing methods from around the world. Current sound therapy projects under development include: binaural beats therapy, a collaborative project with French sound artist Jue Ran LLND; and ASMR (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response) micro-sound healing experiences.

03 Cyan Room: "Speech"

Millennia of voices—hearing excavated languages

On two rows of standing display screens, there are unearthed documents and corresponding audio recordings from 14 ancient languages including Middle Chinese, Sanskrit, Old Uyghur, and Sogdian in Xinjiang region. These documents cover topics such as official/law, economy, learning, medical care, family affairs, etc. Visitors can listen to the reconstructed voices by clicking on the screens and read these letters, contracts, wills, prescriptions, orders, etc. that have been preserved for centuries. These precious documents also represent the "footprints" of cultural integration among multiple ethnic groups in Xinjiang from the 1st century BC to the 14th century AD. The content of this exhibition will be updated every two months. It is said that there are plans for audio content of ancient poems in the future.

04 Blue & White Rooms: "Music" and "Hotan Harmonies"

The breezes of Xinjiang’s fields

Moving into the adjacent blue room, one finds a visitor's upper body enveloped by a massive sea-blue bell-shaped sound dome. The Blue Room contains six such acoustic domes in total. Once inside, visitors are immersed in a 360° surround sound experience showcasing the diverse musical traditions of Hotan, Xinjiang.

Hotan's folk music encompasses philosophical maxims, literary poetry, prophetic teachings, and folk tales, serving as an encyclopedic reflection of local life through the ages. The inaugural exhibition features songs including folk melodies from Langan and Pulu regions, dutar performances by muqam master Abdulla Majnun, love songs accompanied by rawap in mountainous areas, as well as contemporary interpretations of Hotan folk music.

Adjoining the Blue Room is the soaring White Room, currently hosting the "Hotan Harmonies" sub-exhibition. Music forms an organic part of Hotan's living culture, where natural musical talent enables locals to burst into song at any moment - during gatherings, meals, or casual conversations, spontaneous singing arises effortlessly. A video installation captures four folk artists performing the distinctive "Jumping Goat" form: while playing instruments and singing, they manipulate strings attached to a small goat puppet standing on a drum, making the puppet dance vividly to the rhythm of both music and finger movements.

The White Room walls also display the photographic series "All Things"(《万物》) by artist Zhuang Hui, documenting Hotan's geological landscapes, alongside the paper pattern series "Yaksim/Siz"《雅克西姆/斯孜》by artist Dan'er, who creates new designs using traditional Hotan wooden printing blocks on specially layered xuan paper.

05 Red Room "What is Sound?":

Science-Magic Installations That Give Form to the Invisible

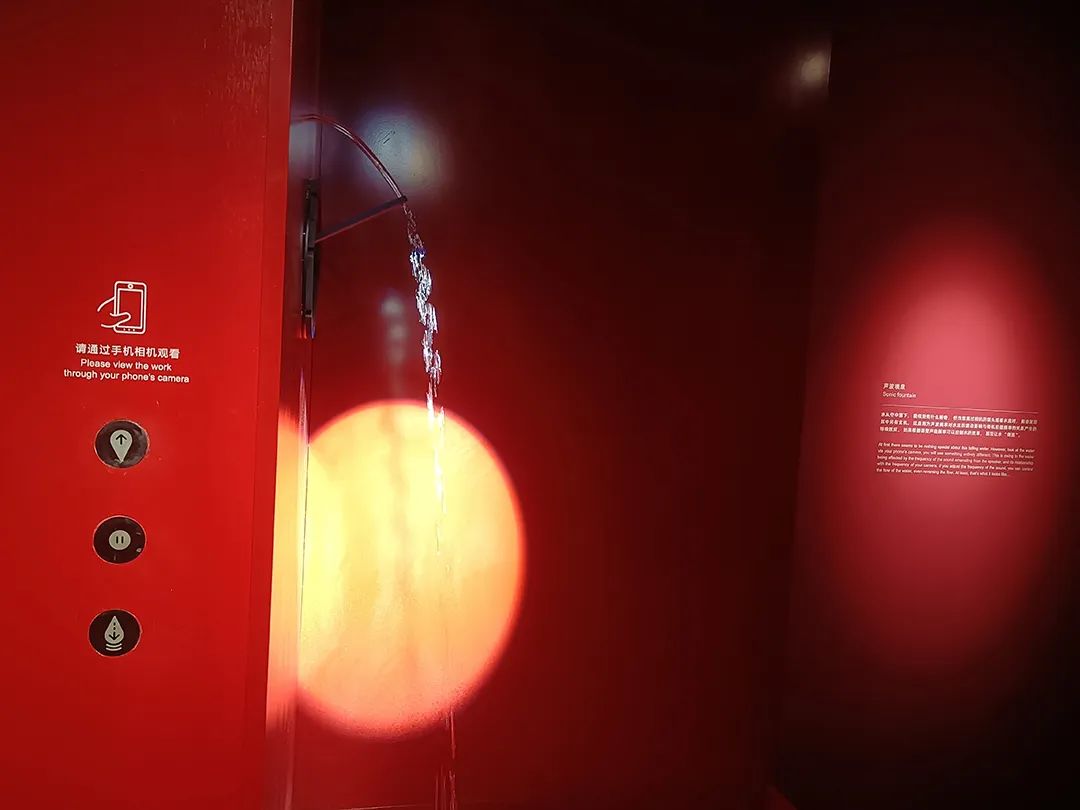

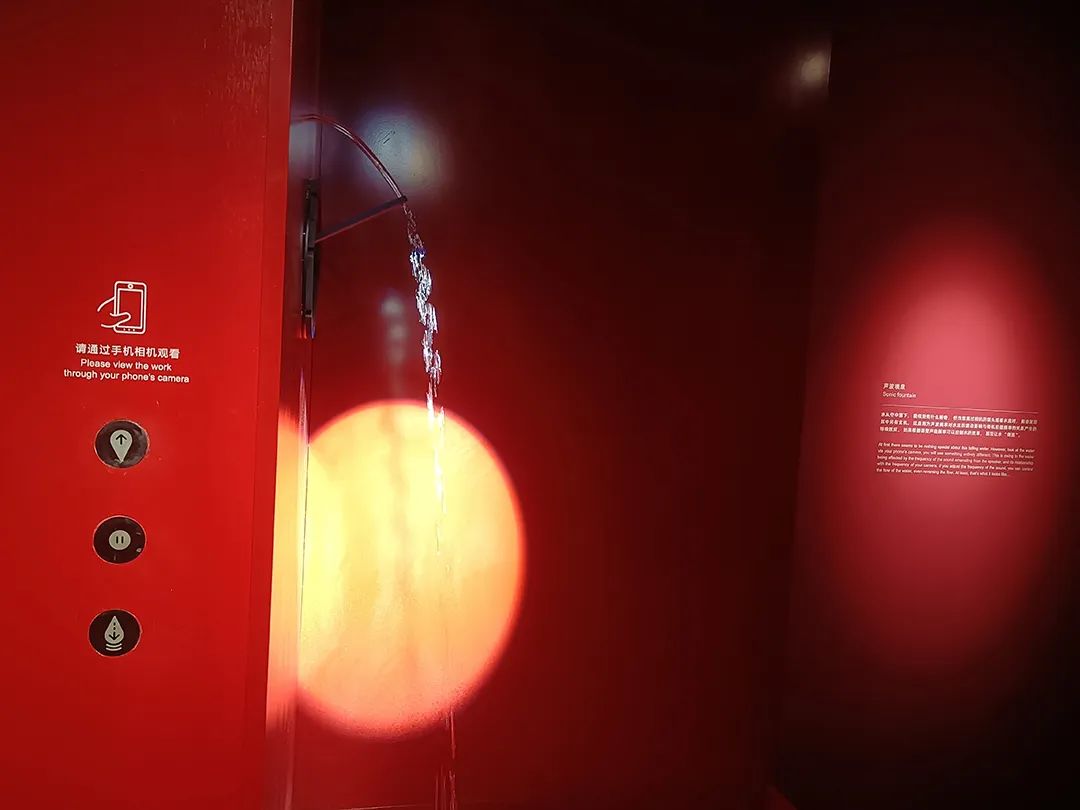

The Red Room is undoubtedly the most fun exhibition area for children. Upon arriving, Colin Siyuan Chinnery immediately introduced the young visitors to the "Sound Wave Fountain." He took out his phone and pointed it at a stream of water - miraculously, the screen showed the water spiraling upward against gravity, flowing back to the fountain's source. "Wow! How does this work?" the children exclaimed, crowding closer in curiosity. This fascinating phenomenon is actually a special effect created by the relationship between sound wave frequencies affecting water vibrations and the camera's shooting frequency.

Designed as a small maze with multiple compartments, the Red Room is divided into three thematic sections. The "Production of Sound" section features three units: "Animal Sounds," "Human Voices," and "Musical Instruments." The museum collaborated with professional animation teams to create a series of vivid and educational science animations. The "Transmission of Sound" section showcases interactive installations that visualize sound, including the Sound Wave Fountain, Kundt's Tube, Cymatics - Water, Sound and Laser, and Cymatics - Chladni Plates. These displays use mediums like water, foam particles, sand, and lasers to demonstrate sound vibrations and waveforms. The "Reception of Sound" section presents educational animations and 3D interactive models explaining the structure and principles of the human ear, along with recreations of early recording scenes before the widespread use of electricity, a timeline of recording technology development, and physical exhibits of recording devices spanning from the earliest technologies to modern MP3 digital players.

06 Black Room: "Sound and Emotion"

Sharing personal sound memories

As the permanent exhibition comes to an end, the large screen in the center of the black room displays various everyday sounds with black background and white characters scrolling like bullet points: sounds from the night construction site, frog calls in Wangjing Park, juggling with a yo-yo, old sewing machines... These sounds are still increasing, and any visitor can upload their own interesting sounds and reasons.

Sound Art Space:

Feedback: Sound in Chinese Conporary Art:1989-2025

The Sound Art Space showcases contemporary artworks related to sound. Its inaugural exhibition "Echoes" presents six artists' works in paired configurations across three independent galleries (A, B, and C):Shi Yong's Public Address Site: A Private Space with Cross Echo is a faithful reconstruction of his 1995 work originally exhibited in "45° as Reason." Within this container-like cubic structure lies a 1990s-style two-room apartment completely outfitted with microphones, speakers, and period furniture/decor - including an old television playing Zhang Peili's early seminal work Water: Standard Version from the ‘Cihai’ Dictionary. In the adjacent gallery, Yin Yi's Waves assembles dozens of black standing fans into a modernist cube. The artist has precisely calibrated each fan's oscillation to create near-perfect wind cancellation, a concept mirrored by the loop of black audio tape encircling the space - this being Xin Yunpeng's Nora's Exit, inspired by Ibsen's A Doll's House. The final gallery features Geng Jianyi's A Complete World, where a housefly navigates like a dimensional traveler through multiple CRT monitor displays. By the entrance, Feng Chen's The Darker Side Of Light covers floor-to-ceiling windows - the artist has programmed the fly's buzzing to control the opening/closing of window blinds.

Sound Activity Center:

"Heaven on Earth" Sound Art Exhibition

At this point, we still had three exhibitions to explore. Our group followed Colin Siyuan Chinnery as we hurried through the scorching sunlight. Before rushing into the building named "Sound Activity Center," Chinnery pointed to a set of solar-powered plastic flower-shaped chant machines on the steps: "This is one of the works in the 'Heaven on Earth' exhibition. This time we've utilized many non-standard exhibition areas to display artworks." Faint chanting emanated from the machines—this piece, titled “Will I Grow More Vigorous and Brighter After Seeing Such Sunlight?”, was created by artist Cheng Biqing.

The "Heaven on Earth" sound art exhibition was curated by renowned artist Ge Yulu, featuring works by 12 artists/collectives: He Zike, He An, Hu Xiangqian, Huang Xiaopeng, Lin Ke, Chi Shilin, Zhang Yunfeng, Ma Qiusha, Shi Jinsong, Yang Jian, Cheng Biqing, and Polit-Sheer-Form Office. Upon entering the elevator, as the doors closed and the car began ascending, a projector suddenly activated, continuing to play Hu Xiangqian's earlier work Workers' Song I: Night (2012) on the closed doors. The footage showed a group of actors, much like visitors crammed into the elevator, squeezed into a tiny security booth, using exaggerated voices and gestures to mimic operatic performances.

Out of the elevator, a silent video work on the wall caught my attention: Ma Qiusha's Star (2013). Flickering points of light repeatedly pierced the darkness—it documented the artist's process of using an electric mosquito swatter in a summer night's grassy field. The description read: "The moment insects collide with the high-voltage wires, brilliant sparks burst forth, their tiny lives extinguished as darkness swallows them." Though the sound of current passing through organic bodies was barely audible, with each "starlight" flash, I could almost hear the lethal "lightning" crackle in my mind.

As we left the Sound Activity Center and headed toward the opposite Ruogu Tower, my peripheral vision caught sight of fitness equipment in an open area nearby. Upon closer inspection, this was Polit-Sheer-Form 's Fitness for all (2014). Often humorously dubbed the "F4 of Chinese contemporary art," Polit-Sheer-Form was founded by Hong Hao, Xiao Yu, Song Dong, Liu Jianhua, and Leng Lin. For this work, they repainted standardized fitness equipment—ubiquitous in public squares and residential complexes nationwide—in their signature deep blue, transforming them into readymade sculptures for visitors to admire or use. Though seemingly silent, this piece instantly conjures the slogan "Fitness for All" in many minds—and when visitors begin exercising on them, the familiar creaks of mechanical friction resurface.

Ruogu Tower:

"Gatehouse Redux—Sound and Concrete"

We finally stepped inside this legendary building, which essentially serves as Colin Siyuan Chinnery's personal exhibition space. On the first and second floors, the roaring sounds from two audio installations created a reverberant soundscape. "Can you feel the sound penetrating your body?" Chinnery prompted. When we reached the more intimate top-floor space featuring a third work utilizing ultrasonic waves, he added, "Now do you sense the sound entering your head?"

This profoundly embodied experience became most immediate with the second-floor installation Chair Sutra. A circle of seemingly ordinary wooden chairs awaited us. But when I instinctively sat down, my body was immediately met with a tingling vibration—hidden speakers within each chair emitted low-frequency sounds that resonated through one's entire physique. "Each chair has a different frequency," Chinnery explained as he watched our group excitedly swap seats like children playing musical chairs. "Arranging them in a circle creates a shared resonance—between people, between sounds."

The Grove:

Lost Bandwidth

By this point, our not-particularly-thorough tour had already lasted over two hours, and readers following along may be feeling fatigued. Fortunately, the final exhibition returns us to nature's sounds: New Zealand artist Dane Mitchell's Lost Bandwidth. Scattered among the trees before a koi pond stand a cluster of black loudspeakers—the very source of the birdsong filling our ears. Chinnery noted that bird traps often take speaker form too, since they use sound to lure their prey.

Mitchell (of Aotearoa [New Zealand]/Tāmaki Makaurau [Auckland]) focuses his practice on institutions like museums, archives and libraries that preserve traces of human civilization—and those things which cannot be preserved: spirit, extinct species, ephemeral transmissions. The birdsongs currently playing in the grove belong to ten vanished species, including the Oʻahu ʻalauahio (Paroreomyza maculata) and Bachman's warbler (Vermivora bachmanii). Perhaps the artist intends these irrecoverable voices to remind us: every present moment is future history.

Sound's bodily experience is fundamentally tactile, yet the Sound Art Museum's sonic offerings also carry rich cultural textures that resist reduction to reproducible audio files. To borrow Japanese sound artist Nelo Akamatsu's description of his own work: "Art expands human perception, making us forget our existence, becoming transparent—thus awakening our senses to experience the world more acutely." These senses extend beyond mere perception into emotion, memory, flesh and spirit... If forced to choose the most unforgettable work from this journey, I'd select He An's Intermittent History of Philosophy (2022) from "Heaven on Earth." Using air pumps and firing pins, the artist generates thunderclap-like concussive booms. This near-violent noise actually springs from collective memory, recalling that mysteriously pure yet palpable sonic blast haunting the protagonist of Apichatpong Weerasethakul's Memoria (2021).

OUI ART Interviews Colin Siyuan Chinnery

(Co-founder of Sound Art Museum, Artist)

OUI ART:

What inspired your focus on sound research and creation?

Colin Siyuan Chinnery:

It's hard to pinpoint a single moment—it accumulated over time. Specifically, in 2005 while working at the British Council's Cultural and Education Section, I curated a sound project called "City Sonic," inviting UK artists and musicians to Beijing for residencies. Among them, musician Peter Cusack launched Your Favorite Beijing Sounds via Beijing Radio, encouraging listeners to reflect on sound's relationship with personal emotion.

Those collected sounds now appear in our permanent exhibition's "Sound and Emotion" section, and we continue this archival practice. Back then, most submissions were mundane urban noises—precisely what connects us to memory, history, culture, and urban transformation. These background sounds often go unnoticed, but when isolated, they become profoundly moving.

In 2013, when the Prince of Wales Foundation funded the restoration of my grandmother Ling Shuhua's former residence as a museum of old Beijing life (now Shijia Hutong Museum at No. 24), I revisited Cusack's archive while planning the sound dimension. Hearing those ordinary sounds instantly transported me back—revealing sound's magical power to trigger bodily memory, like a time machine to its origin moment.

This inspired me to reconstruct Beijing's history through sound. By letting visitors hear historical sounds, each experience becomes personal rather than objective—an alternative historical perspective. Over four years, I created an annex in 2017: "Sounds of the Hutong" (dubbed "Sound Museum" by netizens). This became the foundation for my 2019 long-term project "Sound Terminus," and ultimately, our current Sound Art Museum.

OUI ART:

The Sound Art Museum has presented remarkably rich and multifaceted content since its opening. How would you summarize the vision behind creating this new type of cultural institution in one paragraph?

Colin Siyuan Chinnery:

Sound permeates every aspect of life—what I call its ontological presence. Even silence exerts a direct psychological impact. Our museum seeks to transmit what I see as sound's multidimensional manifestations: humanistic sounds, natural sounds, social sounds, establishing a new kind of sonic community hub.

Simultaneously, sound possesses uniqueness. As numerous disciplines now incorporate sonic exploration, I envision the museum becoming a platform for cross-disciplinary dialogue and collaboration among sound researchers. Furthermore, sound has embeddability. Amid rapid urban development, we aim to integrate sound culture into urban living, public spaces, cultural tourism and education—precisely because sound, as a medium, transcends educational and social barriers to facilitate communication, thereby realizing its socio-cultural experiential potential.

OUI ART Interviews Dr. Edward Sanderson

(Researcher, Curator and Critic Specializing in Chinese Sound Art and Contemporary Art)

OUI ART:

How do you view the uniqueness of the Sound Art Museum within China's and the international museum ecosystem?

Dr. Edward Sanderson:

Frankly speaking, the Sound Art Museum is truly unique—a uniqueness I believe everyone welcomes. Its existence constitutes a direct response to traditional museums' visual-centric paradigm. This paradigm reflects broader sociocultural preferences for images and tangible objects, which possess defined forms and boundaries that make them easily commodifiable and marketable.

This isn't unique to China—museums worldwide share this visual bias. Of course, sound art does appear in museums and galleries; as a distinct cultural production, its history stretches back to 1920s Europe at least. But the "uniqueness" I refer to stems from sound art's resistance to categorization—it constantly overlaps with performance, video, and digital/media art forms. Moreover, due to the aforementioned visual bias, coupled with sound's ephemerality and site-specific fragility, it challenges conventional art space and market circulation systems.

Yet this very resistance constitutes sound art's value: it compels institutions to develop new strategies for exhibiting and communicating sonic works. The adaptation process fundamentally questions institutional roles, potentially birthing new organizational models. Therefore, this museum's explicit dedication to sound art signals a paradigm shift from visual to auditory, while physically manifesting the discourse around sound presentation. Its establishment is nothing short of groundbreaking—terribly exciting!

OUI ART:

Which exhibit or display at the Sound Art Museum left the deepest impression on you, and why?

Dr. Edward Sanderson:

What strikes me most is the museum's ambitious commitment to education and archiving. This dual mission manifests in multiple exhibits: demonstrations of acoustic principles, historical displays of audio technology, and systematic documentation of regional/ethnic sound cultures. I understand the planned "Sound Archive" will provide permanent research facilities for organized sound recordings alongside related documents, books, and vinyl records.As a sound art researcher, I'm particularly intrigued by the museum's collection of historically significant sound-based artworks—some dating to Chinese contemporary art's early periods—and its scholarly reconstructions of lost works. Equally exciting are its commissions of new creations. Beyond exhibitions, the compound's live music venues, bars and restaurants could evolve into a dynamic local cultural hub, potentially energizing sound art's development both domestically and internationally.

OUI ART Interviews Ge Yulu

(Artist and Curator of "Heaven on Earth")

OUI ART:

Could you share the conceptual framework behind your curation of "Heaven on Earth"?

Ge Yulu:

The exhibition's inspiration emerged from a mythical space lost to history—one that seemed to harbor both the decadent excesses of earthly indulgence and the sublime purity of celestial paradise. This tension between polarities created an expansive realm for imagination. It might manifest as a solo performance amid urban clamor, a tranquil grove or starry sky concealing interactive elements, or a space that materializes abruptly—whether flashing across screens, exploding before one's eyes, or waiting silently in corners to be activated. Each artwork interprets this concept through its own distinctive lens.

OUI ART:

How do you define sound art within this context?

Ge Yulu:

Regarding sound as the thematic medium, I emphasize its contextual origins over its linguistic qualities. Some works deliver thunderous or even jarring noises that fade as the listener retreats; others remain quiet until visitors physically interact with them; some maintain complete silence, representing sound's absence. Beyond responding to the theme, each installation adapts to the architectural idiosyncrasies of our multi-level venue—shaded groves, flower beds, courtyards, stairwells, elevators, corridors, service areas, and rooftops all become intentional sites. These works demand audiences to actively engage their perceptual faculties, continually negotiating the porous boundary between art and lived experience.

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Editor:Simone Chen

Writer:顾灵

Designer:Nina

Image provided: Sound Art Museum