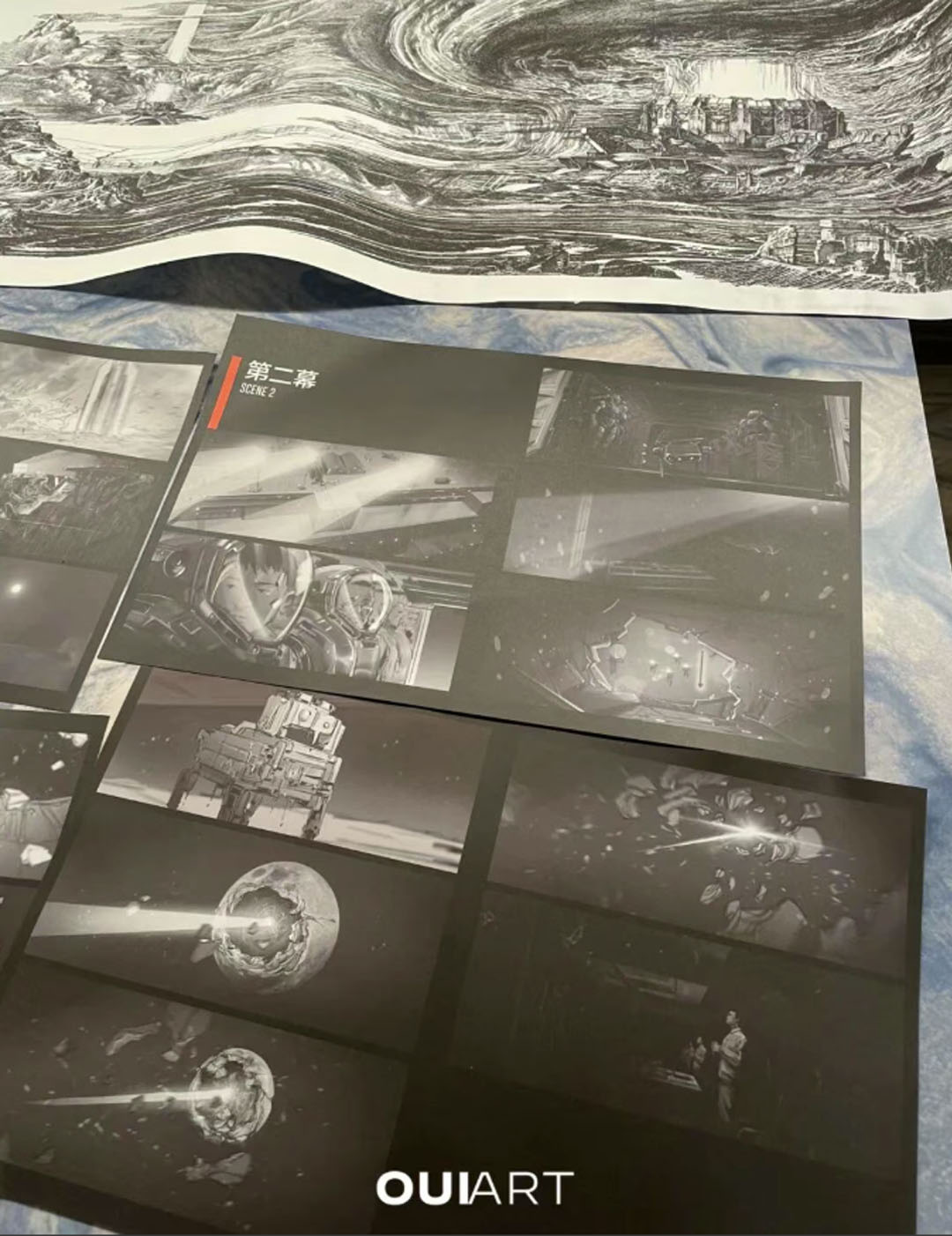

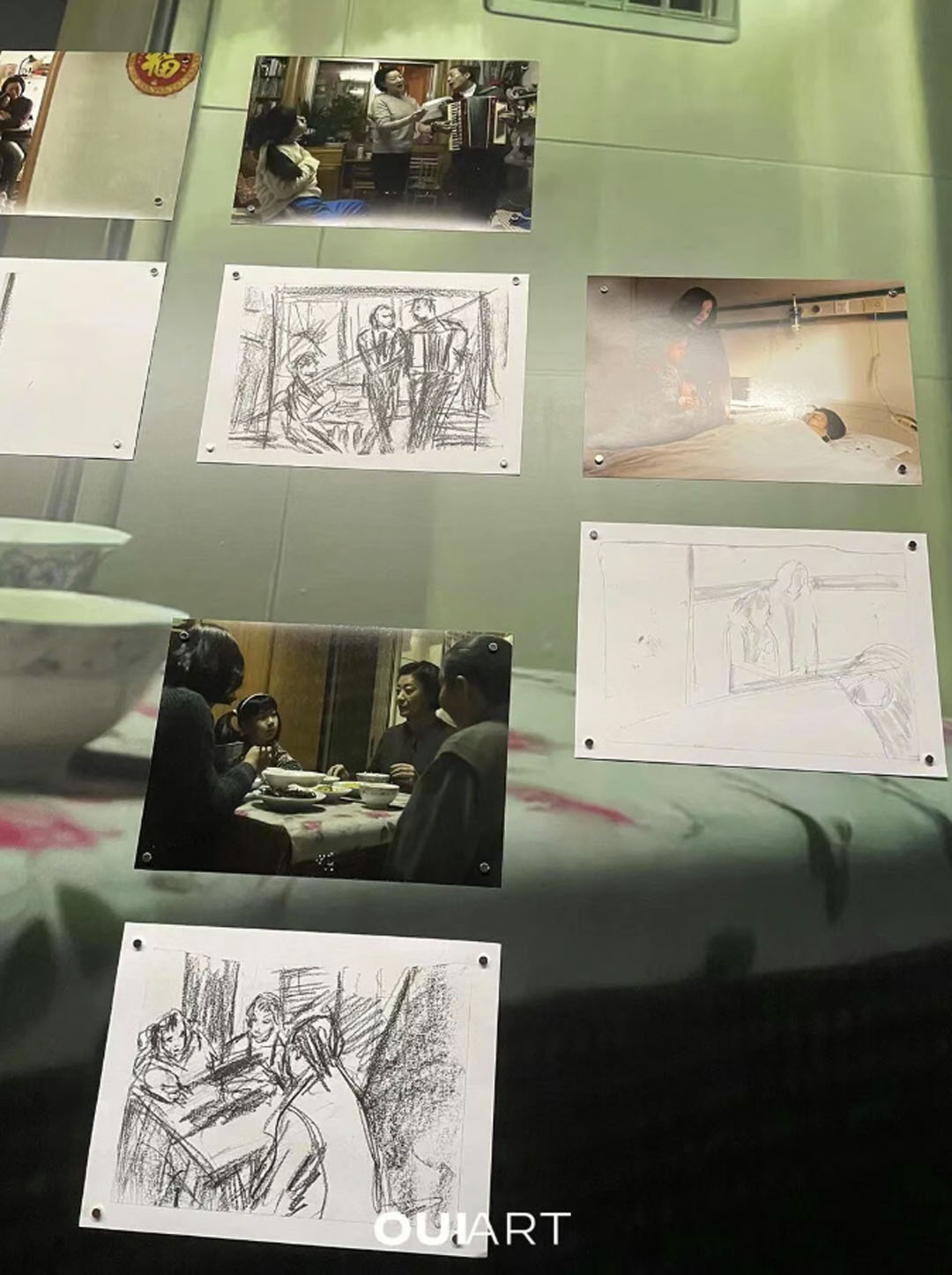

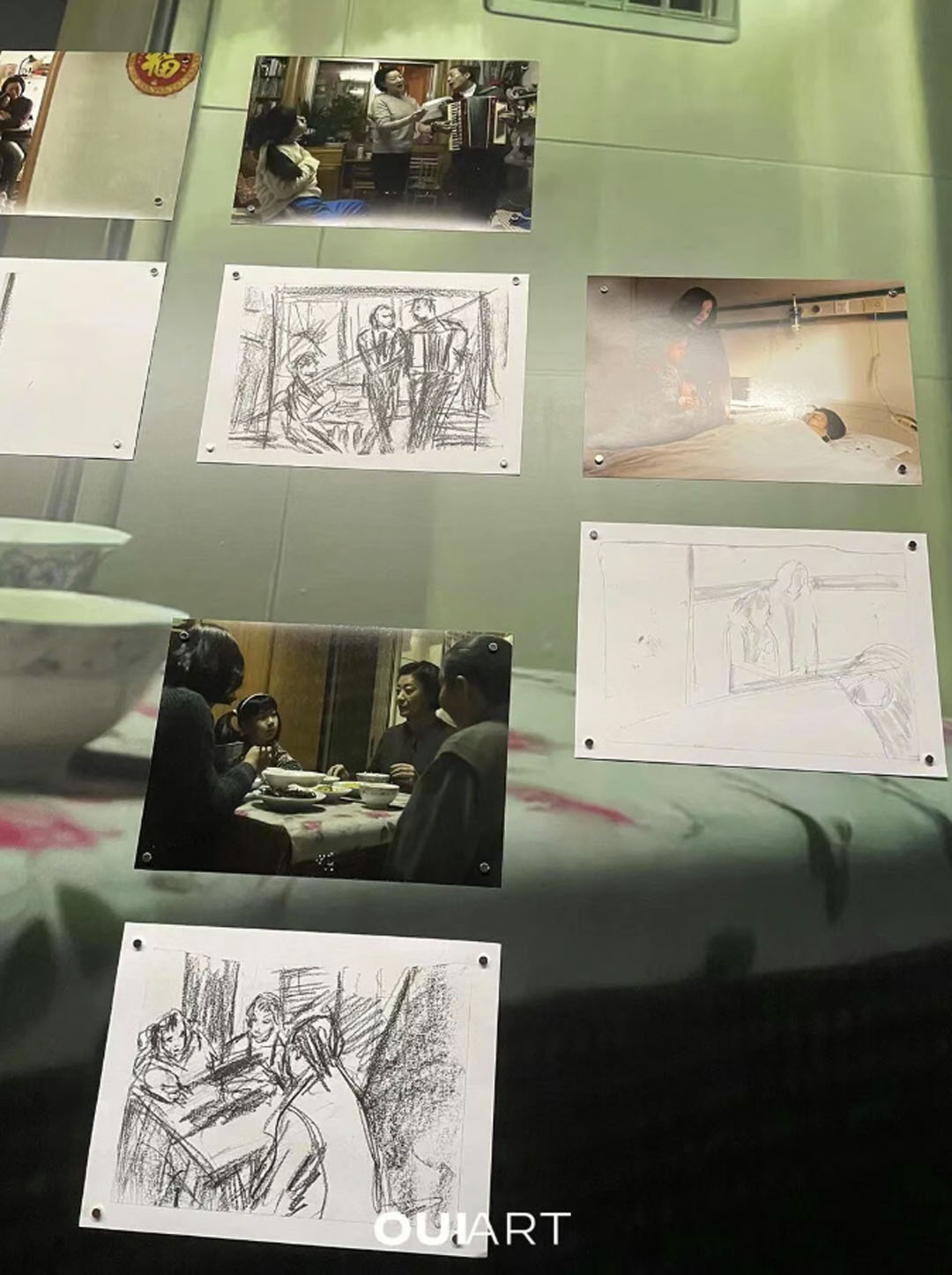

A Kind of Language: Storyboards and Other Renderings for Cinema, handwritten drafts by more than thirty directors and film professionals reveal the diversity and inventiveness of storyboards, as well as their foundational role at the very beginning of cinema. More importantly, the exhibition reminds us that in an age when AI technologies drastically lower the threshold of image-making, narrative voices marked by a strong authorial signature will become increasingly precious.

Thirty-two thousand years ago, when Paleolithic Homo sapiens casually traced a line on a cave wall, humanity entered the age of images. Located in southern France, the Chauvet Cave preserves the earliest known pictorial records in human history and is home to some of the world’s oldest paintings. The cave artworks employ a wide range of techniques—engraving, scraping, charcoal drawing—and most astonishingly, include fifty-three “animated images.”

As early humans waved torches in the darkness of the cave, flickering red and black shadows brought animal figures to life on the rock surface: bison trotting, horses galloping, herds colliding and circling. The torches crackled in the air as light flowed endlessly across the walls. Voices filled the space, then suddenly fell silent. The crowd held its breath, listening to the shaman recount myths and legends. There was something dreamlike in that nocturnal cave—this was the earliest form of cinema, and the first movie theater. Prometheus brought fire to humankind; with fire, humanity developed both civilization and entertainment.

Storyboards: Safeguarding the Consistency of Visual Language

More than 30,000 years after the birth of images, Eadweard Muybridge developed high-speed photographic techniques between 1877 and 1879 that could record and “freeze” motion. On June 19, 1878, The Horse in Motion was born, signaling the implantation of the embryo of the seventh art.

Seventeen years later, the Lumière brothers screened Workers Leaving the Factory and Arrival of a Train at La Ciotatat the Grand Café on Boulevard des Capucines in Paris. Modern cinema officially came into being. While the Lumière brothers used film to record reality, Georges Méliès led cinema into the realm of the surreal. The challenge then became how to accurately translate a director’s imagination into sets, lighting, blocking, and performance.

Before encountering cinema, Méliès was a successful magician and theater owner. A filming accident led him to discover the most fundamental special effect—stop-camera substitution. Across hundreds of short films, he refined techniques such as multiple exposure, dissolves, and slow and fast motion. Today, these effects come bundled as basic presets in editing software, yet once applied, they instantly lend footage a sense of “magic.” This unmistakable quality is Méliès’s signature.

As Méliès expanded the scale and narrative complexity of his films, A Trip to the Moon secured his place in film history. Not only did it deliver the world’s first science fiction film, it also helped standardize cinematic production workflows. Despite its modest 14-minute runtime, the film employed over thirty individual shots—each essentially a self-contained scene. Even by today’s standards, such a number of settings constitutes a large-scale production.

Because its special effects demanded precise continuity between scenes, meticulous planning was required across both pre-production and post-production. To ensure visual coherence, Méliès devised shot sequences and detailed sketches to plan sets and actors’ movements—an early prototype of the storyboard.

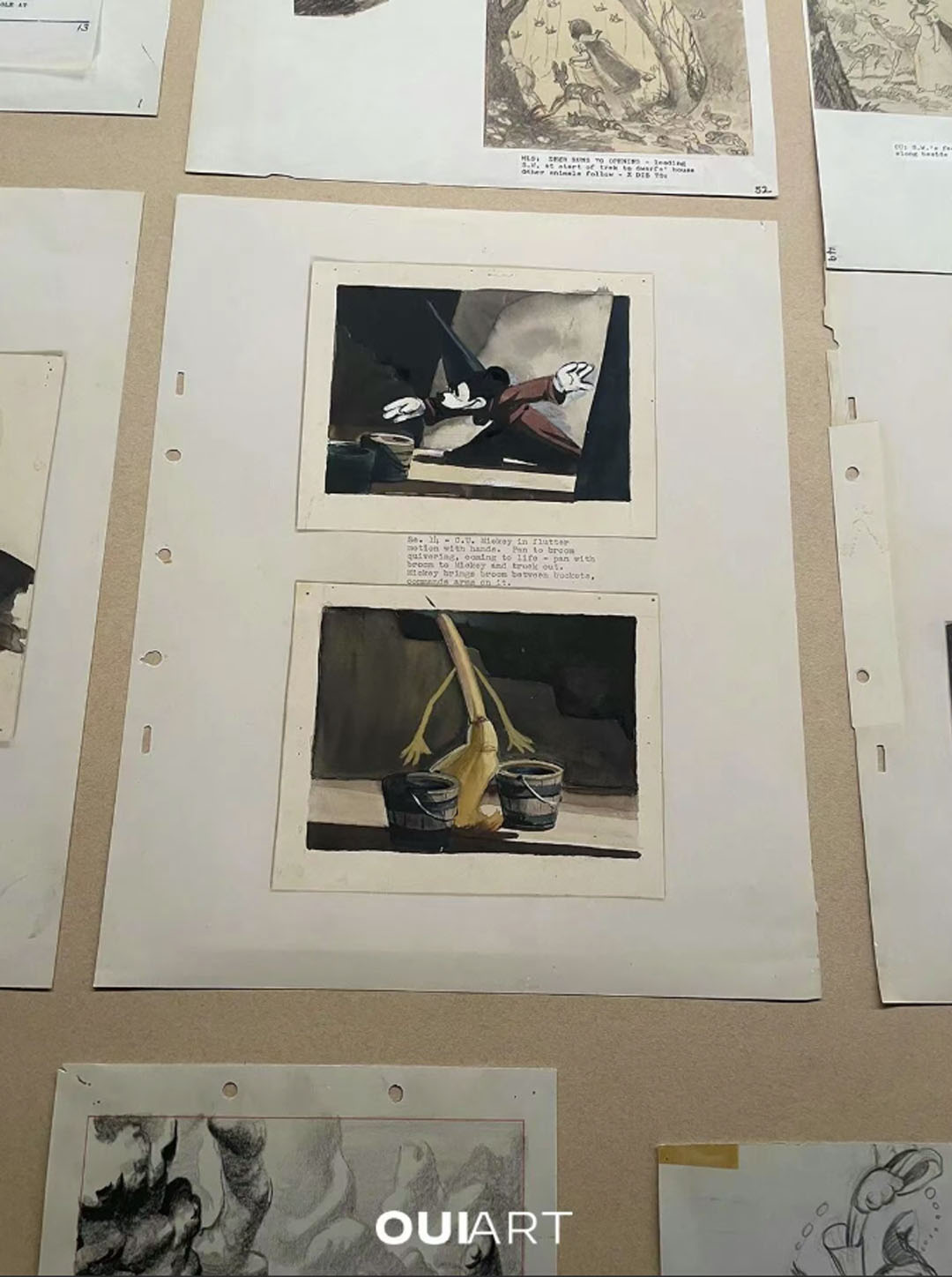

Among all film genres, animation is perhaps the most malleable, capable of visualizing the wildest fantasies. Early hand-drawn animation required teams of artists to laboriously draw every frame. Ensuring that characters remained both richly detailed and visually consistent across multiple artists posed a fundamental challenge.

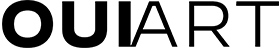

In the early 1930s, Disney animators began pinning character designs and story sketches sequentially onto boards, allowing teams to collectively review character models and discuss narrative progression. Thus, the modern storyboard was born at Disney Studios. Disney’s innovation extended beyond workflow: Fantasia (1940) fused animation with classical music and became the world’s first commercial stereophonic film.

Like premature infants in the animal kingdom, humans require a prolonged period of development before independence. Cinema, too, did not mature overnight. Instead, it gradually integrated sound, color, and other technologies, evolving into a composite art form.

Fantasia, by Walt Disney Productions, 1940 Storyboards by Disney Studio Artist, 1940 Story sketches from The Sorcerer’s Apprentice Exhibition copies, “A Kind of Language: Storyboards and Other Renderings for Cinema” at Prada Rong Zhai, Shanghai

From Text to Moving Image: An Intermediate Form

There are a thousand Hamlets in a thousand minds. Literature, through abstraction, plants characters like seeds in readers’ imaginations, granting them freedom to envision. Each reader forms a personal, absolute image of the text.

Cinema, however, is concrete and sensory. Where language is inherently ambiguous, image-making eliminates ambiguity. Through casting, rehearsal, staging, shooting, editing, and audiovisual synthesis, film condenses countless subjective imaginings into the director’s singular vision. Creation itself becomes an exclusive act.

Storyboards mediate this transition. They translate textual ambiguity into visual sequences, fixing perspective, composition, spatial relations, and camera positions. Psychological time in the script becomes physical choreography in space. The storyboard is an indispensable intermediate form.

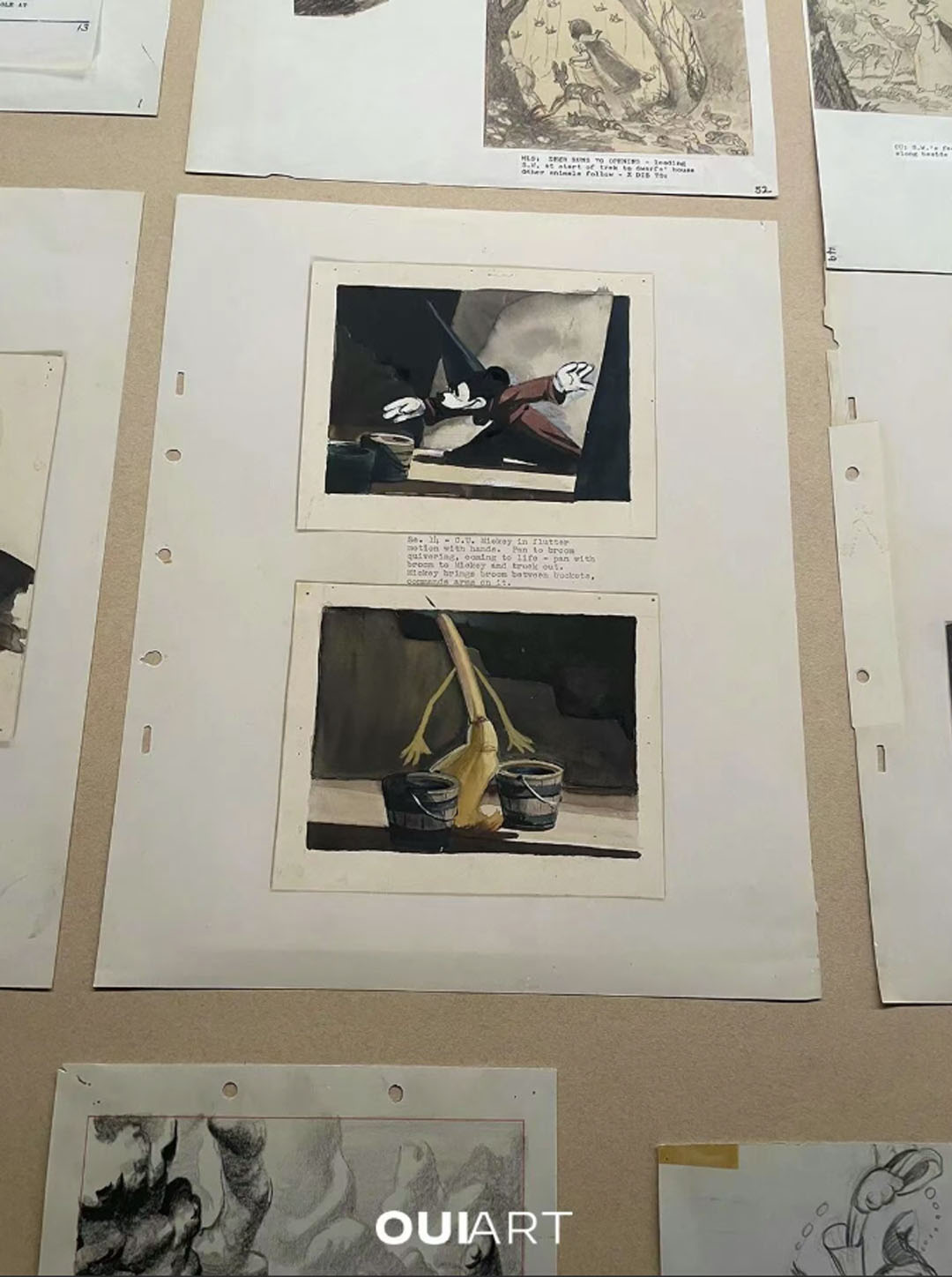

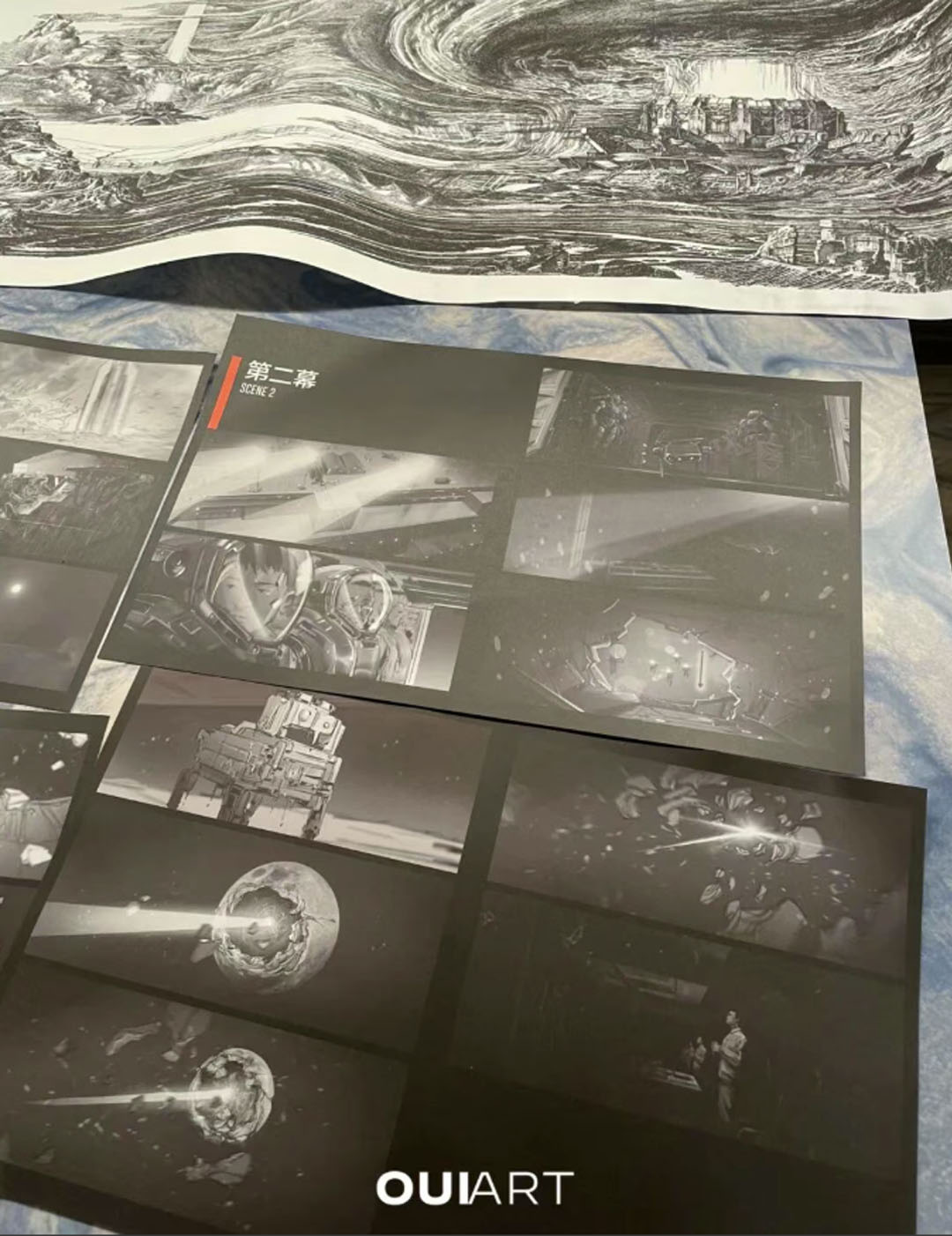

Blockbusters such as Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, Frant Gwo’s The Wandering Earth, Martin Campbell’s GoldenEye, or the auteur-driven Barbarian Invasion by Tan Chui Mui exemplify this role. The first three, products of heavy industrial filmmaking, showcase textbook storyboard precision. In GoldenEye, the opening sequence meticulously conveys velocity at the brink of disaster; in Interstellar, storyboards detail the monumental waves on Miller’s Planet.

Heavy industry filmmaking burns money by the second. Storyboards must ensure that the Leviathan of production stays precisely on course. By contrast, Barbarian Invasion employs minimalist stick-figure sketches drawn by the director himself, proving that storyboards can be as economical or elaborate as needed.

Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron reveals his meticulous temperament: hand-drawn boards annotate dialogue and sound cues, allowing viewers to reconstruct the final film almost entirely. Pixar’s Finding Nemo similarly relied on hand-drawn storyboards to precisely guide CG rendering and compositing.

The Wandering Earth Series, directed by Frant Gwo, 2019–23 Drawings by Xuehao Fei, scene 2: storyboard from the movie The Wandering Earth II, 2023, “A Kind of Language: Storyboards and Other Renderings for Cinema” at Prada Rong Zhai, Shanghai

Storyboards are the architectural blueprints of cinema—essential drawings that allow collective imagination to construct cathedrals of moving images beyond language and time.

Reading Directorial Style Through Storyboards

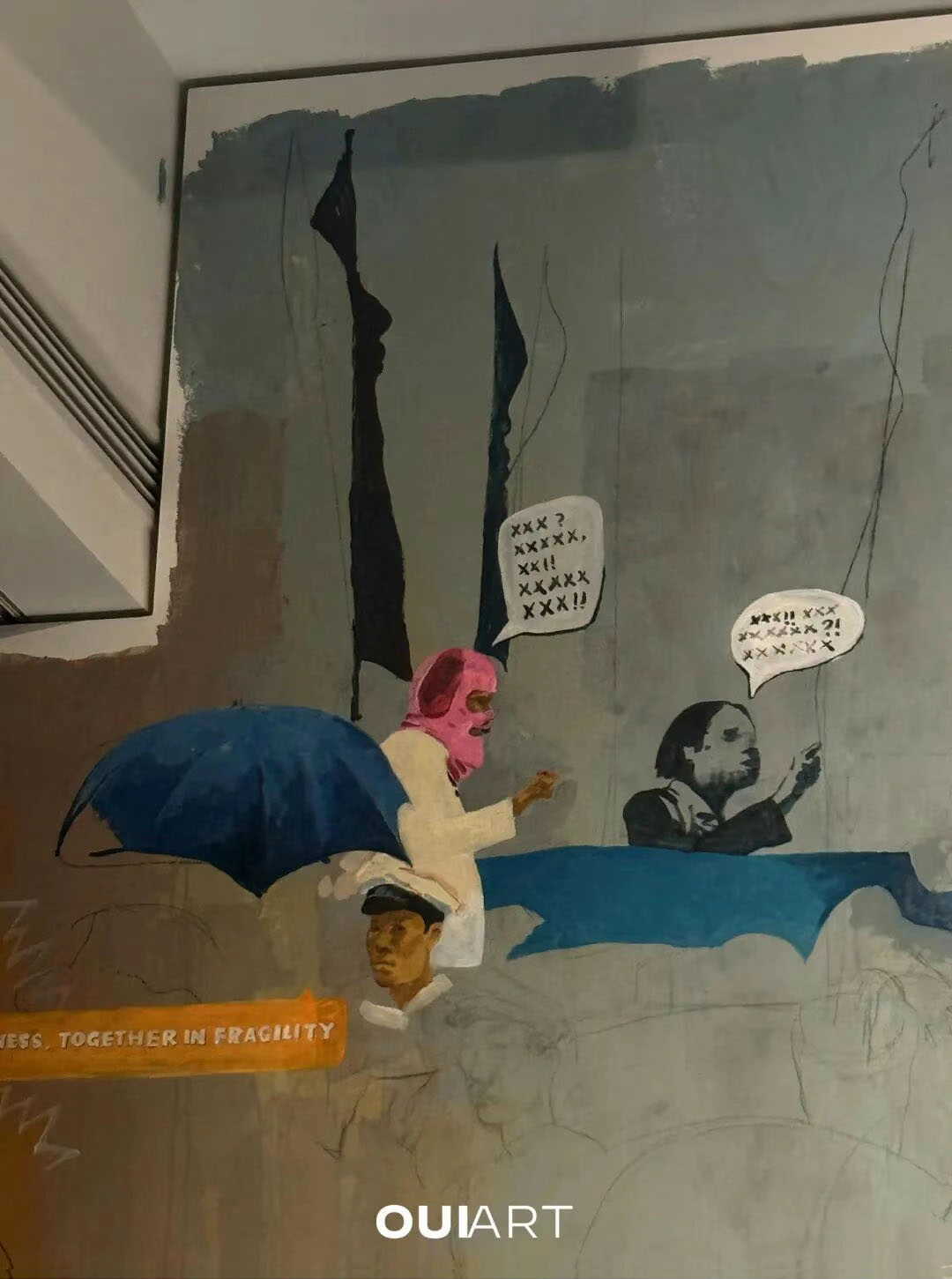

Every great director possesses a distinctive visual language, and storyboards reveal these differences vividly.

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s unrealized Dune storyboard book is legendary—a paper film that shaped science fiction history. Though never produced, it influenced Star Wars, Alien, Blade Runner, and The Fifth Element.

Displayed in A Language, Jodorowsky’s boards—drawn under his direction by production designer Max Douy—resemble architectural plans, emphasizing set design and camera placement.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca marked his Hollywood debut and remains his only Best Picture Oscar winner. Produced by David O. Selznick (Gone with the Wind), it exemplifies storyboards as instruments of power. Gone with the Wind was the first live-action film fully storyboarded, ensuring stylistic unity despite multiple directors.

Hitchcock perfected the principle that “storyboards equal editing,” filming only what he needed. When Selznick attempted to re-edit Rebecca, he found no surplus footage. The storyboard dictated the cut.

Steven Spielberg, bridging eras, transformed storyboards into a dynamic industrial standard. His boards for Close Encounters of the Third Kind treat light as a compositional entity rather than illumination, ensuring precise integration of optical effects.

European auteurs, by contrast, emphasize personal vision over industrial efficiency. Ingmar Bergman’s sketches for Persona reveal the conceptual genesis of its iconic “merged face” montage.

Wim Wenders’s Wings of Desirestoryboards establish the angelic camera perspective. Wes Anderson’s animated boards for The Grand Budapest Hotelreflect his obsessive visual control. Agnès Varda’s Salut les Cubains uses photographs as storyboards, creating a photo-montage film with rhythmic dynamism.

Salut les Cubains, directed by Agnès Varda, 1964 Storyboards by Agnès Varda, 1962

Exhibition copies, “A Kind of Language: Storyboards and Other Renderings for Cinema” at Prada Rong Zhai, Shanghai

In the Age of AI: Is Cinema Dead?

When photography was announced in 1839, painter Paul Delaroche declared, “From today, painting is dead.” History proved otherwise. Yet new technologies inevitably redirect mass art forms.

Cinema replaced painting as the dominant popular art of the 20th century, unifying global audiences across languages and cultures. Today, AI tools—Sora, Runway, Midjourney, and others—again provoke the refrain: “Cinema is dead.”

AI transforms storyboarding radically. Anyone can now generate professional-grade storyboards through language alone. Previsualization becomes instantaneous, cost-efficient, and infinitely mutable. Storyboards may soon approach final cuts, and fully AI-generated films are imminent. “Everyone is a filmmaker” may arrive sooner than Joseph Beuys’s “everyone is an artist.”

Yet technological democratization also risks stylistic homogenization. Spectacle becomes cheap. Perhaps AI will instead compel us to return to stories rooted in human experience—irreproducible, personal, author-driven narratives that resist easy replication.

In the end, what survives will not be technique, but voice.

“A Kind of Language: Storyboards and Other Renderings for Cinema” at Prada Rong Zhai, Shanghai

Producer: Tiffany Liu

Editor: Tiffany Liu

Designer: Nina

Image: From Prada Rongzhai and Oui Art On site shooting