Surrealism, n. m. Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express — verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner — the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern. ——André Breton

Artificial intelligence, fake news, war and peace—living in the "now" can sometimes feel "surreal," can't it? Perhaps that's why today is the perfect moment to revisit the Surrealist movement from a century ago.

In 1924, in a small studio in Paris's bohemian district, the young poet André Breton was drafting a preface for his poetry collection Poisson Soluble . He merely intended to share some thoughts on creative philosophy, but those 21 pages of heavily edited manuscript unexpectedly became the Manifeste du surréalisme. In it, he called for a new art form guided by the subconscious, liberated from rational control.

In 2024, we ride the escalator to the top floor of the Centre Pompidou, gazing at Paris through the transparent walls, and enter an exhibition commemorating 100 years of Surrealism at 10 PM on a Thursday night.

My French companion and I pass through the gaping mouth of a monster and red velvet curtains—the prologue to the exhibition, the entrance to L'Enfer. The Centre Pompidou, in collaboration with magician Abdul Alafrez, has meticulously recreated the façade of the legendary cabaret L'Enfer, which once stood below Breton's apartment and was a frequent haunt for him and his peers. Today, it feels like a metaphor: viewing an exhibition to attain a long-lost ideal state—being consumed by something far beyond one's own perception.

There’s also an optical illusion here: from the side, those entering through the monster’s mouth seem to disappear, echoing the black-and-white Surrealist film playing on a screen at the entrance, where several men walk into lampposts and vanish.

The word "sentimental" is rarely associated with Surrealism, but as we walk down a corridor lined with photo-booth-style portraits, that emotion washes over us. Everyone looks so young, and another thought strikes: Was this really a century ago? Yves Tanguy sticks out his tongue at the camera; Jean Aurenche, Marie-Berthe Aurenche, and Max Ernst mug together; Luis Buñuel tilts his head back, eyes closed... Fun, free, joyful—indeed, of all modern art movements, the Surrealists might have been the best at enjoying their own "revolution." In this space, the specter of freedom lingers—these now-departed individuals, intimate yet rebellious colleagues and lovers, infused an "ism" with unprecedented emotional intensity.

After the immersive portrait tunnel, we reach the "heart," the true starting point of the exhibition: a display case at the center of the room holds the original manuscript of the Manifeste du surréalisme., on loan from the National Library of France. As curator Marie Sarré notes, even among those familiar with art movements, knowledge of this manifesto's content is surprisingly limited:“Even among insiders, who might otherwise quote manifestos including that of Futurism, people don’t really have Breton’s text in mind. And yet when you hear it, it really stays with you. You realise how current it is.”

Indeed, Breton’s voice reciting the Manifesto fills the room. The curatorial team collaborated with Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music to generate his voice using artificial intelligence.

The spiral, or labyrinthine, exhibition design draws inspiration from Marcel Duchamp’s unrealized 1947 concept for Galerie Maeght in Paris. Fascinated by spatial interaction, Duchamp envisioned a maze-like structure where viewers could move along paths, experiencing works from shifting perspectives. Today, at the Pompidou, the exhibition forgoes strict chronology in favor of 14 thematic chapters (including a prologue) tracing Surrealism from 1924 to 1969.

"Surrealism is not a formalism. It was a collective adventure, even a philosophy. It lasted 40 years, and one could argue it never truly ended. This movement was vibrant, constantly reinventing itself." — Curator Marie Sarré

The trajectory of dreams, a nightly ode to the night

Many fail to grasp Surrealism or dismiss its flights of fancy as mere posturing. Undeniably, misinterpretations have abounded since its inception a century ago. How much do we truly understand today? "Dreams" and "night" remain the most direct gateways into Surrealism.

In the Manifeste du surréalisme., Breton posed a question: “Can’t the dream be used in solving the fundamental questions of life?” The former medical student was deeply influenced by Albert Maury’s 1861 Sleep and Dreams, the first neurological study of dreaming. In 1916, while working at a neuropsychiatric center in Saint-Dizier, Breton encountered Sigmund Freud ‘dream-analysis techniques for treating patients. Soon after—as most know—Surrealists transplanted psychoanalysis into poetry, recreating dream narratives and the bizarre imagery hovering between sleep and wakefulness.

The chapter "Trajectory of the Dream" features Odilon Redon’s magnificent work where a huge, sleeping female face emerging from the sea; Dora Maar’s 1934 photograph of a hand reaching from a seashell; Salvador Dalí ’s Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee(Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening); and projections of Dalí’s dream sequences for Alfred Hitchcock ’s Spellbound,1945

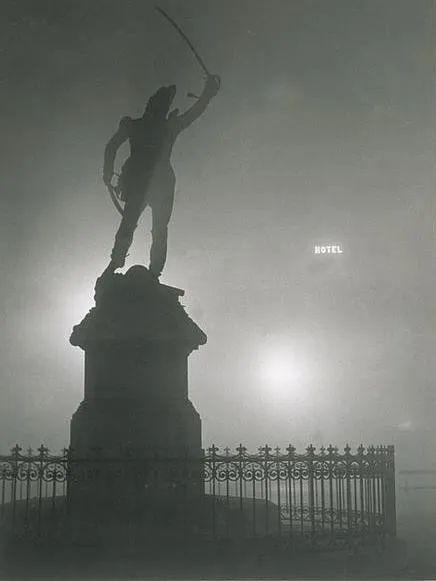

Dreams are inseparable from night. Together, they shatter everyday logic, sideline reason, and immerse the viewer in Surrealism’s liberating alterity. As night owls, fans of Nosferatu (1922) and the fictional criminal Fantômas, Surrealists wholeheartedly embraced the "dark night" (a potent symbol amid the era’s political turmoil).

The current chapter, "Hymns to the Night", also represents the opposition and integration between night and light, reality and dreams. Rene Magritte's “The Empire of Light”(1954) is the highlight of this exhibition. There is also the Romanian artist 布拉塞Brassai - I would like to say a few more words about this foreigner from Paris at that time. Born on September 9, 1899, Brassai believed that the number 9 had some connection with his life experiences. He also emphasized his birth background quite a lot because he was from the same hometown as the famous legendary figure Dracula the Vampire. In 1924, he came to Paris. For a period of time, he led a nocturnal wandering life, exploring every corner of Paris in the Bohemian style. "I was shocked by the constantly unfolding scenes of this never-ending city before me. I wanted to find a way to record them. Finally, a woman lent me an amateur camera, and I used it to capture these scenes that had been entwined in my heart for a long time."

Was he a surrealist? I often wondered, compared to his peers, he seemed a bit exceptional; the simplest way to explain this is to look at the difference between him and the core figure of surrealism, Man Ray. Braque created a large number of photographs for the surrealist group, especially for the "Minotaure" (a half-human, half-beast monster in Greek mythology) magazine. But he was not obsessed with Man Ray's magic-like photography; instead, his photographs appeared more "realistic" and more "everyday". He proposed the term "straight Surrealism", stating that "Surrealism lies within us, in the things we do not see, in the normalcy of the everyday.”

He explained, "The surrealism of my images was nothing more than the real made fantastic by vision… I was simply trying to reveal every aspect of daily life as if seen for the first time." Braque was obsessed with dark-toned styles and close-up shots, especially street graffiti or minute details. His first photography collection, "Paris by Night", shocked France upon its publication: because people discovered that he had captured almost all the facets of Paris's nightlife, starting from the gas lamps lit by night watchmen, to all kinds of drunkards, homeless vagrants, courtesans, circuses, backstage of dance troupes, gay parties, and the other side of the faces of the upper class in the lower class... Only after reading all his works can one better understand what he meant by 'surrealism', and at the same time, one will also discover his interest in primitive impulses and desires.

A beautiful corpse should drink fresh wine

If the dreams and the dark night we just mentioned approach the surreal from the perspective of the topic, then the two chapters "Lautréamont" and "Chimera" are still related to the topic, but more directly, they start from the creative methods of the surrealists, giving us the possibility to get a glimpse of the whole picture (which, in my opinion, is the most interesting part of the exhibition).

A sentence from the poetic novel " Les Chants de Maldoror" (written by Comte de Lautréamont) became the creed of the Surrealists: “It is beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella.” But, why is this so?

If we go back in time a little further, in 1914, the journal "Vers et Prose" published the works of a forgotten writer who died in 1870 at the age of 21: Isidore Ducasse, whose pen name wasComte de Lautréamont. The poet Philippe Soupault once said that reading "Les Chants de Maldoror" changed his life path. He sent a copy to Breton, who then shared this discovery with Louis Aragon.

This work violates logical structure and is filled with rambling fragments, ambiguous images, and calls for violence and destruction. Comte de Lautréamont clearly poured his entire life into this work; from Homer, Dante to Musset, Gautier... everything was poured out at once. Mature literary images were used by him, and the connection was made through his unique wisdom and arrogance.

Half a century later, Breton "discovered" Comte de Lautréamont and regarded him as an idol. This is perfectly normal. In an adventure that has yet to begin, Comte de Lautréamont died mysteriously early, making it even more tragic. “It is beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella.” I guess when Breton saw this sentence, he might have had the urge to slap his thigh. Comte de Lautréamont went ahead for them, finding the way out of "aesthetics": that is, breaking free from the constraints of logic. Thus, just like the encounter between an umbrella and a sewing machine, surrealism acquired a trait that could be both a definition and a principle - collage.

In the exhibition hall, there is a direct simulation and interpretation of this "umbrella meeting sewing machine" by Man Ray. Next to it are Dalí's Lobster Telephone, Victor Brauner's "Loup-table", and Unica Zurn's bizarre sketches.

Of course, when it comes to collage, we must also mention its other prototype, "Exquisite Corpse". What did the artist behind that idea create? There was a kind of game similar to a board game: Exquisite Corpse. It was very simple, requiring only a pen, a piece of paper, and more than three players. Players wrote a word on the paper in turn according to the rules, folded the paper over the words, and passed it to the next player to continue writing. This chain of word writing often resulted in absurd short stories. The name "Exquisite Corpse" originated from the sentence that emerged when the surrealists first played this game: "Le cadavre exquis boira le vin nouveau." (优美的尸体应喝新酒。)

Not satisfied with just words, the surrealists gradually expanded it into a drawing game. The rules remained the same as before, except that each player no longer wrote words but drew pictures. After each player finished drawing, they folded the paper, revealing only a small part of their own drawing, and then passed it to the next player to continue drawing. It is said that these small drawings can reflect each person's subconscious. No matter what is drawn, when the paper is unfolded at the end, those "monsters" are often "dirty" and vivid, and are "impossible to imagine with a single-minded thinking". They are actually the magical techniques of the surrealists to release their subconscious power. Soon, the game was expanded into creative activities.

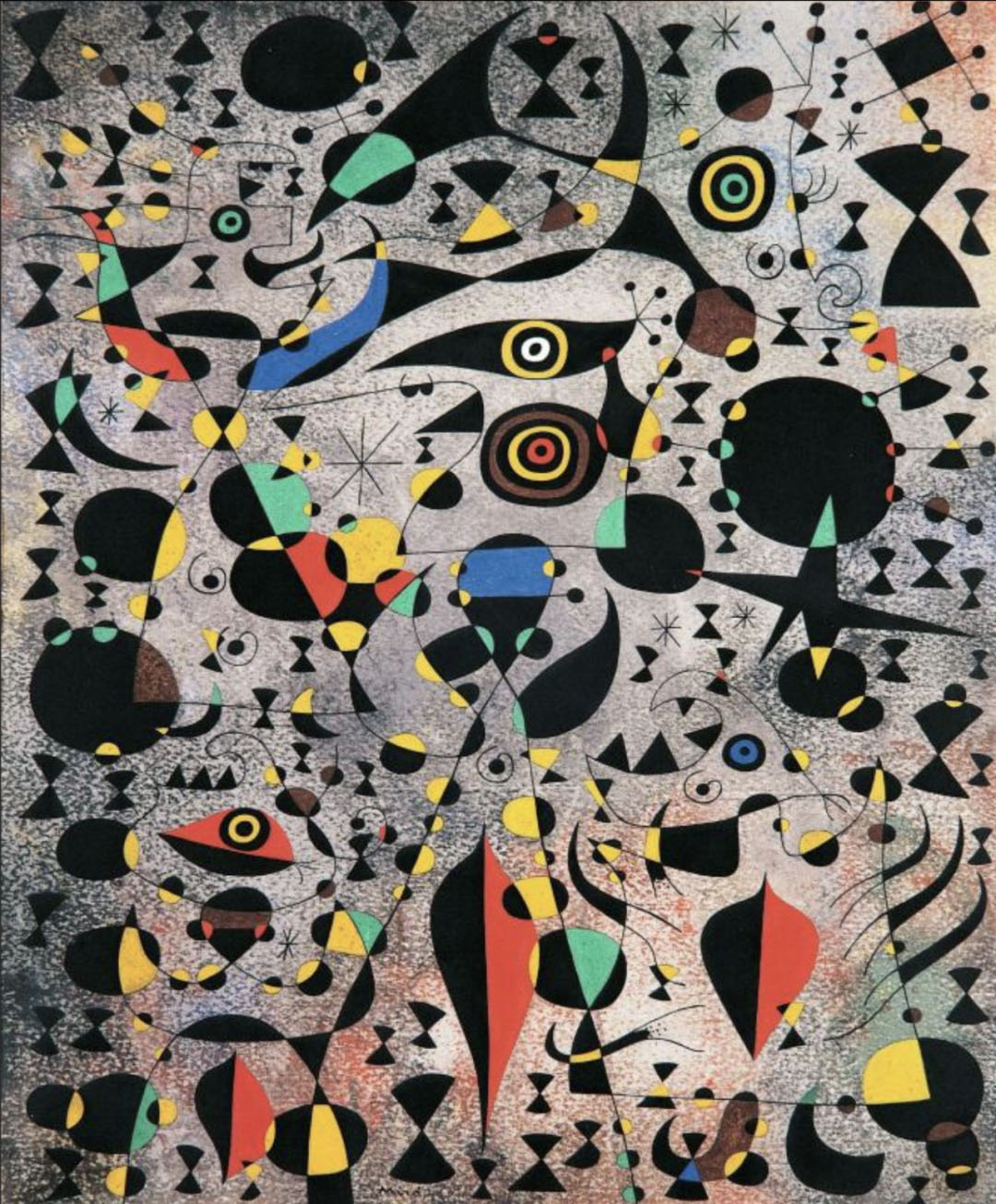

“Exquisite corpse” has become a symbol of the collective creation of surrealism, and even until the late 1960s, it was a commemoration of the good times in the Rive Gauche Café. To some extent, understanding the “Exquisite Corpse” means understanding surrealism more easily? The three main weapons of surrealism can be said to be the “Exquisite Corpse”, frottage, and free association. What is frottage? It is to cover various objects with paper, apply color, and then transfer the texture - just like when we used to cover coins with paper and "draw" them. And free association means drawing the first reaction in your mind when given a word. It is said that the best at free drawing is Miró.

Perhaps you might say that one aspect of surrealism is "irresponsible", because the artists have handed over the creative authority to the mind - more precisely, to some unknown force that creates the art. When they adopt this approach, art and desire come uninvited.

Alice and the Forest, Philosophers' Stone Galaxy Universe

The subheading above represents several scattered but interrelated chapters. The first overall feeling that must be mentioned - this is the extremely concentrated literary quality of the 100-year exhibition of Surrealism - can even be said to be that without literature, there would be no Surrealism. The most typical examples include the previously mentioned Comte de Lautréamont as well as Lewis Carroll. The latter's interest in dreams, madness, and unconscious thinking, as well as his desire to create a new reality world, coincided with the Surrealists' appreciation of unexpected ideas.

In the "Alice" chapter, one can observe the appreciation of surrealism for "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland", perhaps also a celebration of the dreamlike childhood? André Breton once wrote: "Childhood is perhaps the closest thing to true life." In his "Selected Works of Black Humor" (1940), he listed Carroll as one of the pioneers of surrealism: "All those who retain a spirit of revolt will recognize in Lewis Carroll their first teacher in the art of playing truant."

Alice symbolizes miracles, illogicality and humor. Concurrently, in the "Forest" chapter, the surrealists regarded the forest as a realm of profound miracles, a possible form of a maze, and a location for an enlightenment journey. The forest was Max Ernst's favorite theme. What impressed me was Leonora Carrington's work "Green Tea" (1942), which depicted a lush green area with strange mythological creatures and floating figures scattered in the background.

"The philosopher's stone" is a significant analogy between the two. This was mentioned by André Breton in his 1929 "Second Manifeste du surréalisme". Bernard Roger, a member of both the alchemists and the Surrealists, regarded alchemy as a "science of love, based on a natural analogy through which all domains and levels of existence communicate with each other." Breton borrowed the language of the alchemists and chose "I seek the gold of time"(Je cherche l’or du temps) as his epitaph.

"Cosmos" is actually the entire exhibition maze, the closest point to the exit. It is the conclusion, a metaphor for the future. Remedios Varo's “Papilla Estelar” is, in my opinion, the core of this chapter; and the center of this painting is a female figure wearing a monk-like robe, sitting in a tall tower. She uses a strange mechanical device to transform the stars in the sky into food and feeds it to the moon trapped in a cage. It is worth noting that Varo's works are widely regarded as feminist expressions within the Surrealist movement. This one, you could say, explores the connection between women's creativity and the universe. They seem to have mastered the power to transform the energy of celestial bodies spiritually.

In Prologue aux manifestes du surréalisme (1942), André Breton rethought the position of humanity in the universe: "Man is perhaps not the center, nor the focal point of the universe." Different from the modern human tendency to separate themselves from nature and attempt to become the masters of nature, the surrealists were more inclined to draw on the medieval narratives about the microcosm of the universe (the human body as a miniature version of the universe) and the macrocosm (the entire universe). They had an intuition that another kind of relationship could still be established between humanity and the world.

Love, love desire, desire

I can think of no other "ideology" that has explored the relationship between "eros" and "thanatos" , as well as the desire for love and destruction, more seriously than Surrealism. It is no wonder that Surrealism holds such an important position in today's queer and alternative movements. Surrealism has never been detached from reality; instead, as André Breton pointed out, it is a "method for changing the world here and now by revealing the hidden psychic mechanisms that govern our lives."

When entering "The Tears of Eros", there was a notice on the wall of the exhibition hall, roughly stating, "Some of the works in the next two rooms may offend you due to their explicit sexual nature. It is not recommended for minors to visit." Here, we have no choice but to refrain from displaying Man Ray's naked photographs - and in front of that photographic work, my immediate reaction at that moment was, "What beautiful organs!"

Love and passion, it is undeniable, "are the most representative characteristics of 'surrealist works', primarily because they contain erotic metaphors." André Breton placed eroticism at the core of the Surrealist project and redefined "L'Amour fou” in the most straightforward way: a passionate fervor that can lead to mental instability. The love of Surrealism evolved into a controversial and revolutionary emotion.

In the pursuit of absolute "concentration", the Marquis de Sade (imagine that the word "SM" originated from the name of Sade) who became famous in the 18th century with "Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma" inspired the surrealistsAlberto Giacometti with "Objet Désagréable", Hans Bellmer with "The Doll", Joyce Mansour with "Objets Méchants", and her passionate poems...

It's time to stop writing. Just like the 14 chapters, the more one knows about surrealism, the more there is to be unknown, fascinated by, and also missed. The curator, Marie Sarre, was right when she said that this exhibition aims to showcase "the diversity of surrealism". "Surrealism is not a formalism. It was a collective adventure, even a philosophy. It lasted 40 years, and one could argue it never truly ended. This movement was vibrant, constantly reinventing itself."

In 1969, the writer Jean Schuster announced in Le Monde that the so-called "end" of the Surrealist movement had arrived. Later, Surrealism gradually fell out of favor as consumerism was on the verge of sweeping in. People began to be keen on revealing the real, chaotic and ambiguous "happiness" of reality. Even, they believed that Surrealism seemed to only lead to nothingness and destruction. Dreams were no longer magical, and material things became more reliable.

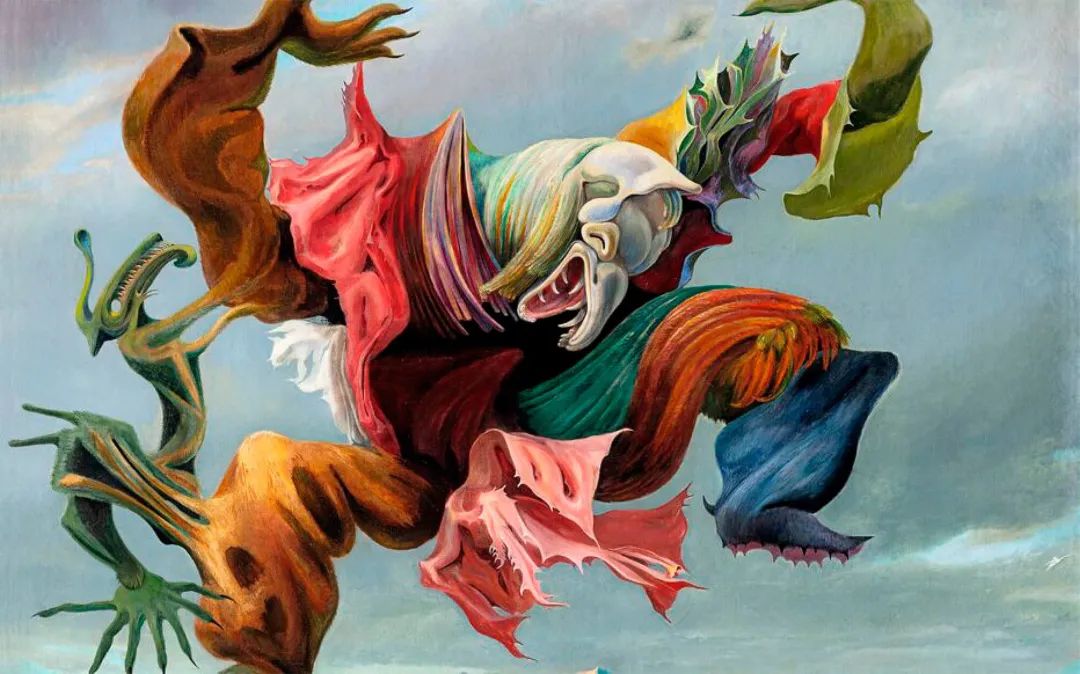

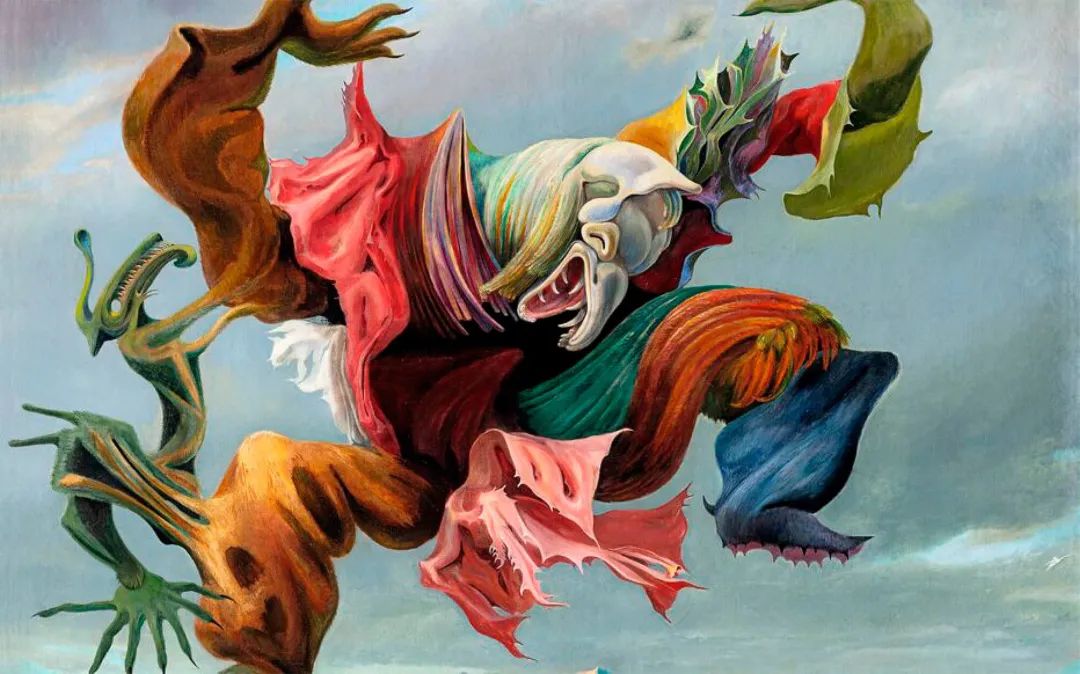

Let's take a look at that exhibition poster: In 1937, Max Ernst painted a huge monster, and he named it "L'Ange du foyer" (Le Triomphe du surréalisme). He said this painting was related to the rise of fascism, and viewers could sense that chill. And what about the subtitle? He seemed like a prophet.

The prophecy was correct. The most enduring legacy of the Surrealist movement was the very word "surreal".

A hundred years from now, the world will be full of twists and turns, surreal and unpredictable. But will we still have the desire for collective adventures and revelries, the strong urge, and the natural expression of our talents?

Surrealism may indeed still be relevant: While we were preparing this article, on November 20th Beijing time, as a quintessential work of surrealism, René Magritte's "The Empire of Light" was sold for 121 million US dollars (approximately 877 million yuan) at Christie's in New York, setting a new record for the highest auction price for an artist's work and topping the list of the most expensive artworks sold in 2024. This piece was also a highlight of the Pompéi Surrealism Centennial Exhibition.

The "Surréalisme" exhibition will be on display at the Centre Pompidou in Paris until January 13, 2025. After that, it will continue to tour to Brussels, Madrid, Hamburg and Philadelphia. Each exhibition will provide a unique interpretation of the Surrealist movement based on the local cultural and historical background.

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Editor:Tiffany Liu

Writer:徐卓菁

Designer:Nina

The images are partly taken by the author and partly sourced from the internet