One of the founders of modern art, a pioneer of Cubism, and a central figure in Surrealism, Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) long ago surpassed the identity of an artist to become a symbol of twentieth-century cultural thought and visual revolution. A true watershed figure in the history of modern art, Picasso continuously absorbed and transformed multiple visual languages—including Impressionism, Symbolism, Neoclassicism, and Surrealism—while opening unprecedented artistic paths through relentless experimentation. His work continues to reshape how contemporary audiences understand images, emotion, and reality.

Imagine Picasso as a walkable timeline. At the Museum of Art Pudong, Picasso Through the Eyes of Paul Smithunfolds more than seventy years of stylistic transformation into a sequence of navigable segments, drawn from the artist’s entire career. Like a clearly plotted city map, the exhibition moves from the Blue Period through Cubism, circles back to Neoclassicism and Surrealism, and proceeds toward Picasso’s late years. The route is explicit; the milestones unmistakable.

Picasso Through the Eyes of Paul Smith originates from the exhibition Picasso Celebration: The Collection in a New Light, held at the Musée national Picasso-Paris in 2023 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the artist’s death. For its Shanghai presentation, the Paris museum and the Museum of Art Pudong jointly selected 80 works, preserving the exhibition’s conceptual core while reconfiguring its display to respond to the Pudong museum’s open and distinctive architecture.

Sir Paul Smith, a key figure in contemporary creative and fashion culture, serves as the exhibition’s artistic director and collaborator, offering a new interpretive pathway into Picasso’s work. Rejecting the conventional “white cube,” Smith constructs an immersive exhibition environment structured around color, pattern, stripes, and objects. The result is a rhythmic dialogue between artworks and space, guiding viewers step by step into Picasso’s universe and inviting them to resonate with its vitality.

By contrast, at this very moment, Moderna Museet in Stockholm offers an almost opposite entry point. The exhibition Late Picasso functions like a countdown: ninety minutes that push viewers directly up against the surface of the paintings, forcing a confrontation with the immediacy of the unfinished.

Seen together, the tension is striking. One exhibition trains us how to approach Picasso anew—lowering the threshold through design and display—while the other protects Picasso’s refusal to cooperate.

At Moderna Museet, the experience begins even before entering the gallery. Tickets require the selection of a specific time slot, followed immediately by a second instruction: please remain here for ninety minutes. It reads like an honest warning—a pre-set rhythm for viewing. What awaits is an almost oppressive immediacy. The faster we move, the more we understand Picasso’s speed; the longer we linger, the more we see how those “casual” marks are in fact repeatedly resisting completion.

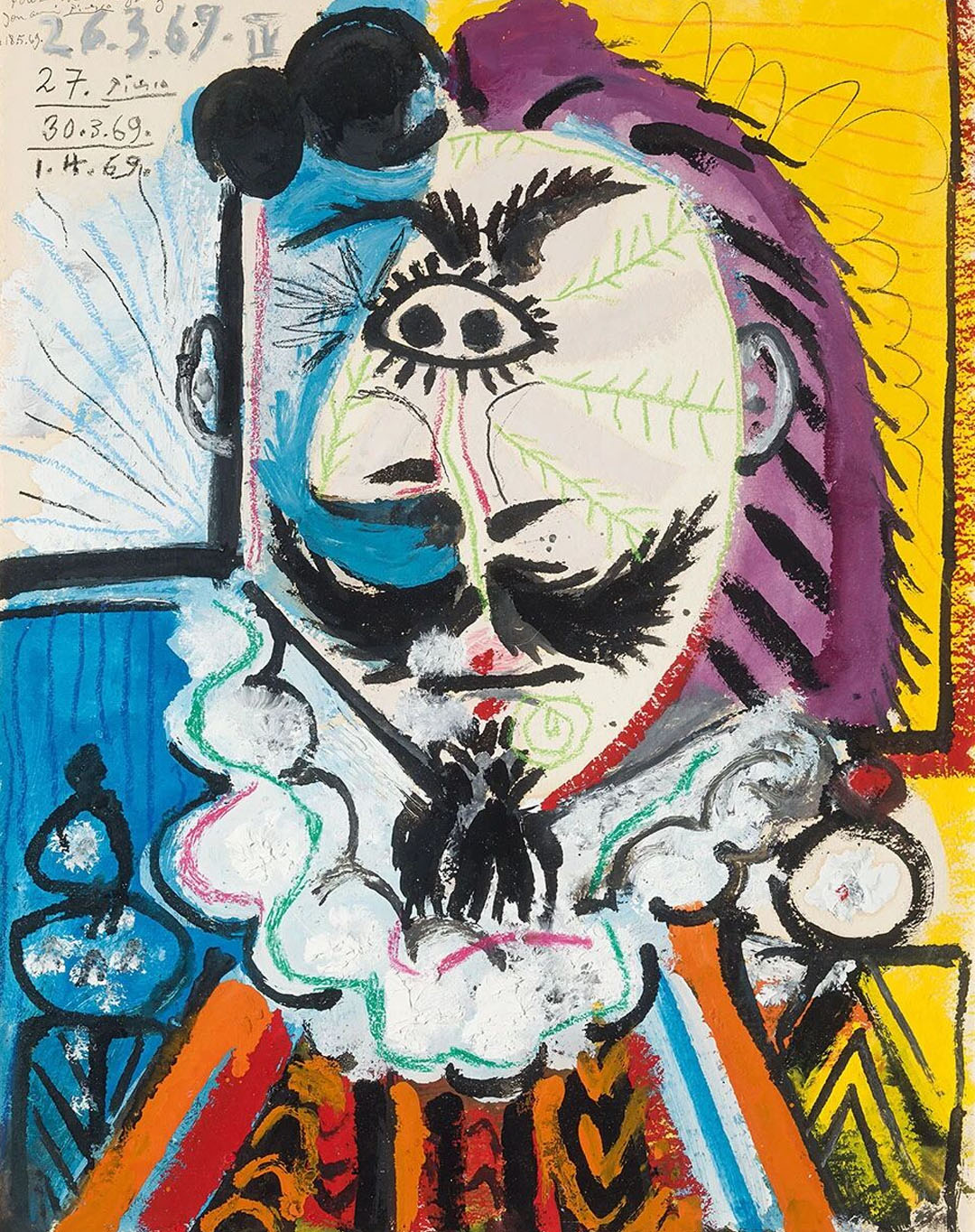

Late Picasso is often misread as careless, repetitive, or uncontrolled. Yet in the gallery, it first registers as a physical sensation: lines feel freshly laid down, colors still seeping outward, surfaces not yet cooled. Brushstrokes seem to have just left the skin; figures appear to have been pulled from the canvas, still carrying body heat. Incomplete, yet intense; unpolished, yet urgent.

Moderna Museet describes this condition as “A Refusal to Conclude.” These works privilege urgency over resolution. They reject polish and finality, turning the canvas into a threshold between art and life.

We are accustomed to placing Picasso within a “genius narrative,” where each period becomes a neatly labeled chapter. Late Picasso does the opposite. It brings us into the final decade of the artist’s life—a state that resists archiving and refuses summary.

Entering Through Speed

The first task inside the gallery is simple: stop in front of a figure or a head. Watch the speed of the stroke—how a skeletal structure is assembled in seconds, how eyes ignite, how a mouth is dragged away in a single line. We begin to realize that the entry point to late Picasso may not be iconography but kinetics. He is not depicting a person so much as turning the act of seeing into action.

This explains why late Picasso so often makes viewers uneasy. It is as if politeness has been removed. There is no longer a negotiation with the viewer, no patient buildup. He throws the present moment directly at us. Curator Jo Widoff notes that these works are more concerned with urgency than completeness; in the gallery, this becomes tangible. What we see is not a refined “final version,” but a sketch still warm to the touch, enlarged into a painting.

Again and again, we encounter images that contain little information yet deliver enormous impact—like messages compressed into extreme brevity, carrying immense emotional bandwidth. Picasso seems to encode the visual world into rapidly transmissible short codes. One might even call this a pre-digital low-bitrate aesthetic: minimal data, maximal energy.

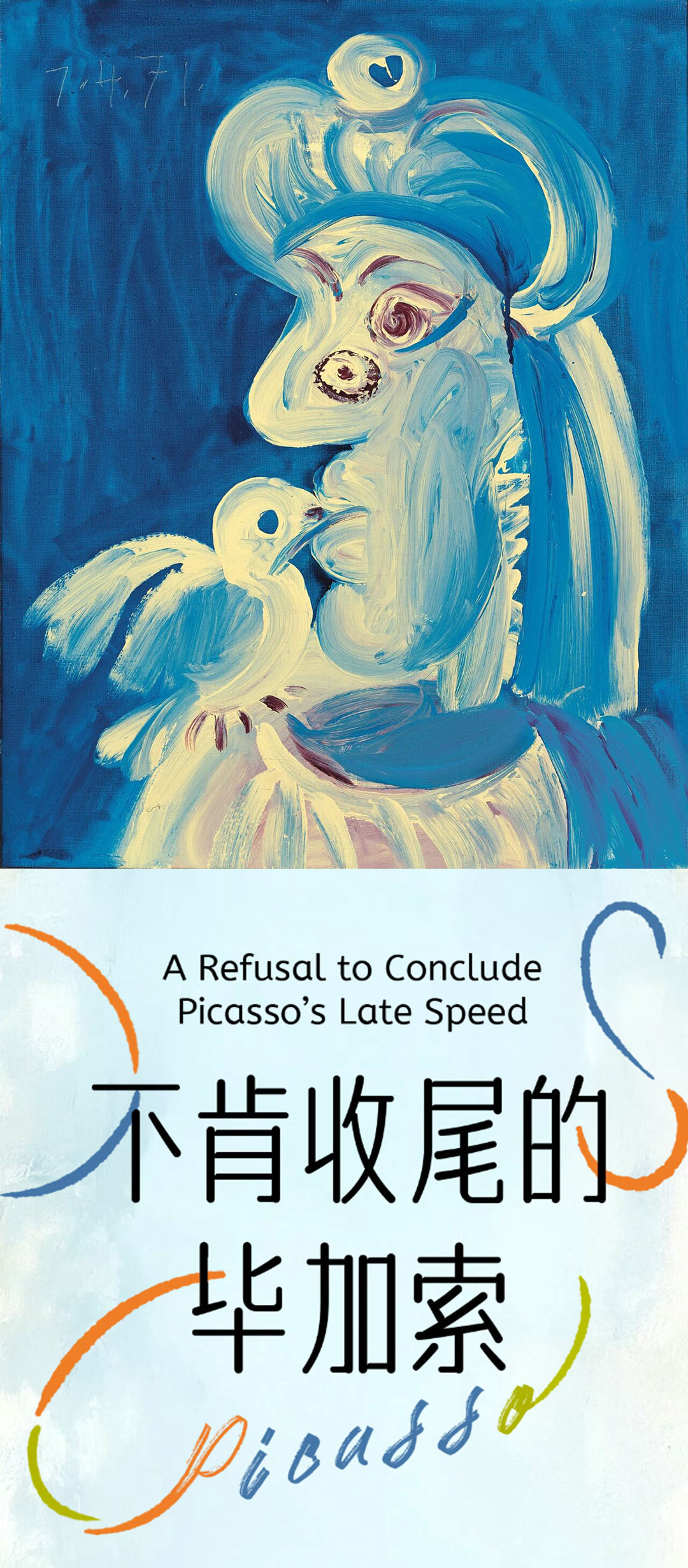

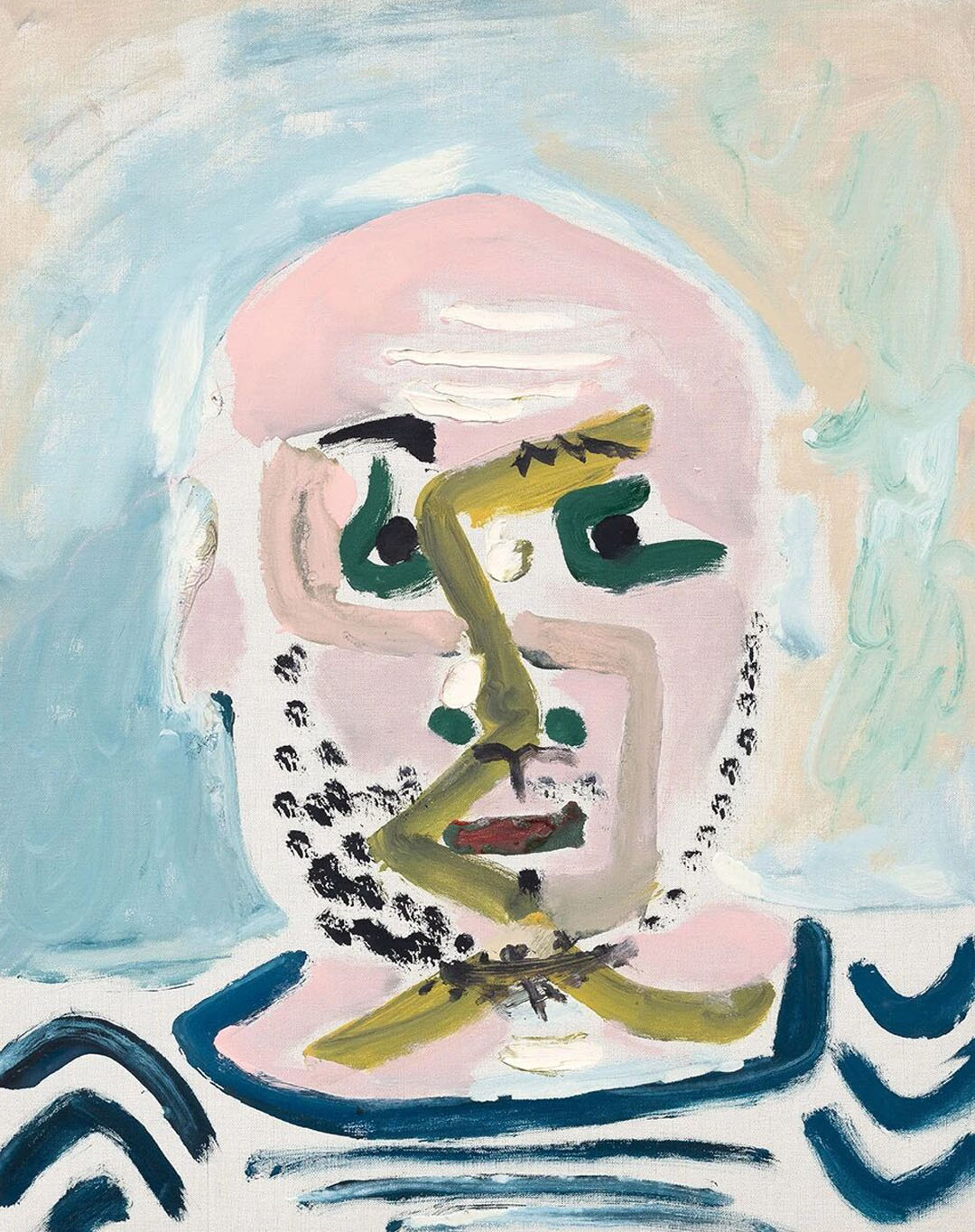

"Buste d'homme", May 1965, a large-scale bust portrait featuring a pink face set against a light blue background

Repetition as Method

Naturally, as these strokes pass before our eyes, biographical memories surface. In 1961, Picasso purchased Notre-Dame-de-Vie in Mougins, where he lived and worked in his later years. In 1965, at the age of 84, he underwent stomach surgery and recuperated in the South of France. Recovery did not slow him down; instead, it pushed him toward an even more concentrated, solitary working state. The Musée Picasso-Paris has described this period as marked by “the frenzy and freedom of the final years.”

Many late heads appear as byproducts of speed, but they can also be understood as acts of will: in the face of aging and time, painting becomes not a passive record but an active resistance—compressing life into the canvas through faster, more direct means.

If speed defines the first section, repetition defines the second. Similar poses, recurring figures, nearly homologous compositions. Much of the fatigue directed at late Picasso stems from repetition—as if he were merely copying himself. Yet within the framework of Late Picasso / Code of Painting, repetition is not depletion but training. He continuously varies a single subject, pushing a visual language to its limits.

Scholarly accounts often link the Musketeer motif to Picasso’s post-surgery recovery. In an article on Mousquetaire et nu assis (1967), Christie’s notes that the musketeer figures emerged in late 1966 and quickly developed into a significant body of work. During his recovery at Notre-Dame-de-Vie, Picasso read Shakespeare, Balzac, Dickens, and Alexandre Dumas. The story itself resembles a late painting: an aging man in a southern French villa restoring his body while projecting his intellectual fire into literature and historical drama—allowing musketeers, nudes, parody, desire, classicism, and smearing to collide on the canvas, continuing a dialogue with art history through role-play.

Here, repetition becomes method. The same subject is not used to tell more stories, but to change the encoding—shorter, sharper, more direct. We begin to understand that the true protagonist of late Picasso is not theme but painterly procedure itself: painting as an ongoing self-experiment.

With only minutes left, the best thing to do is return to the two heads where we first stopped. The second viewing feels like a change of eyesight. Within seemingly casual distortions, classical structures emerge; within childlike simplifications, a masterful command of body, composition, and pictorial tradition becomes visible.

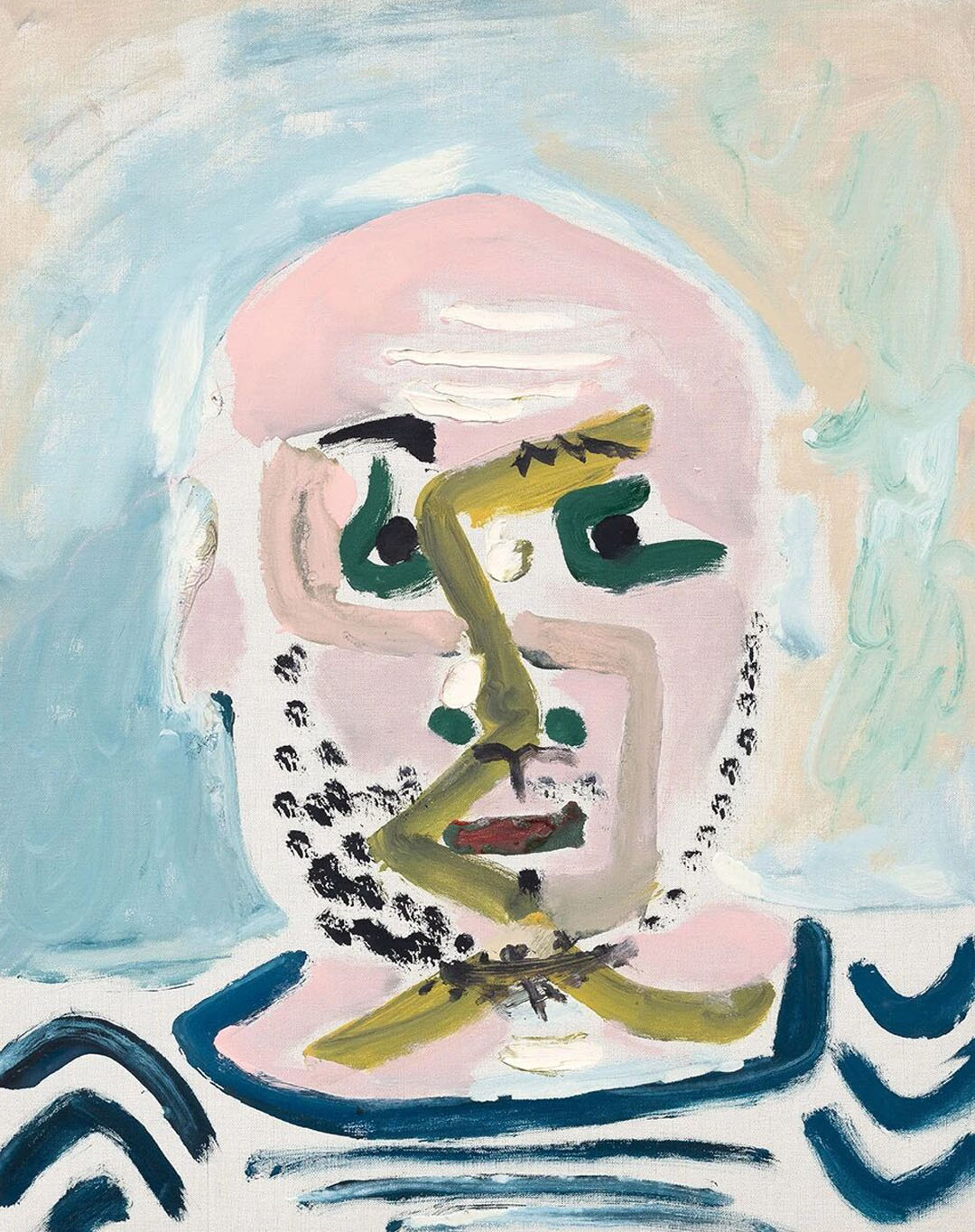

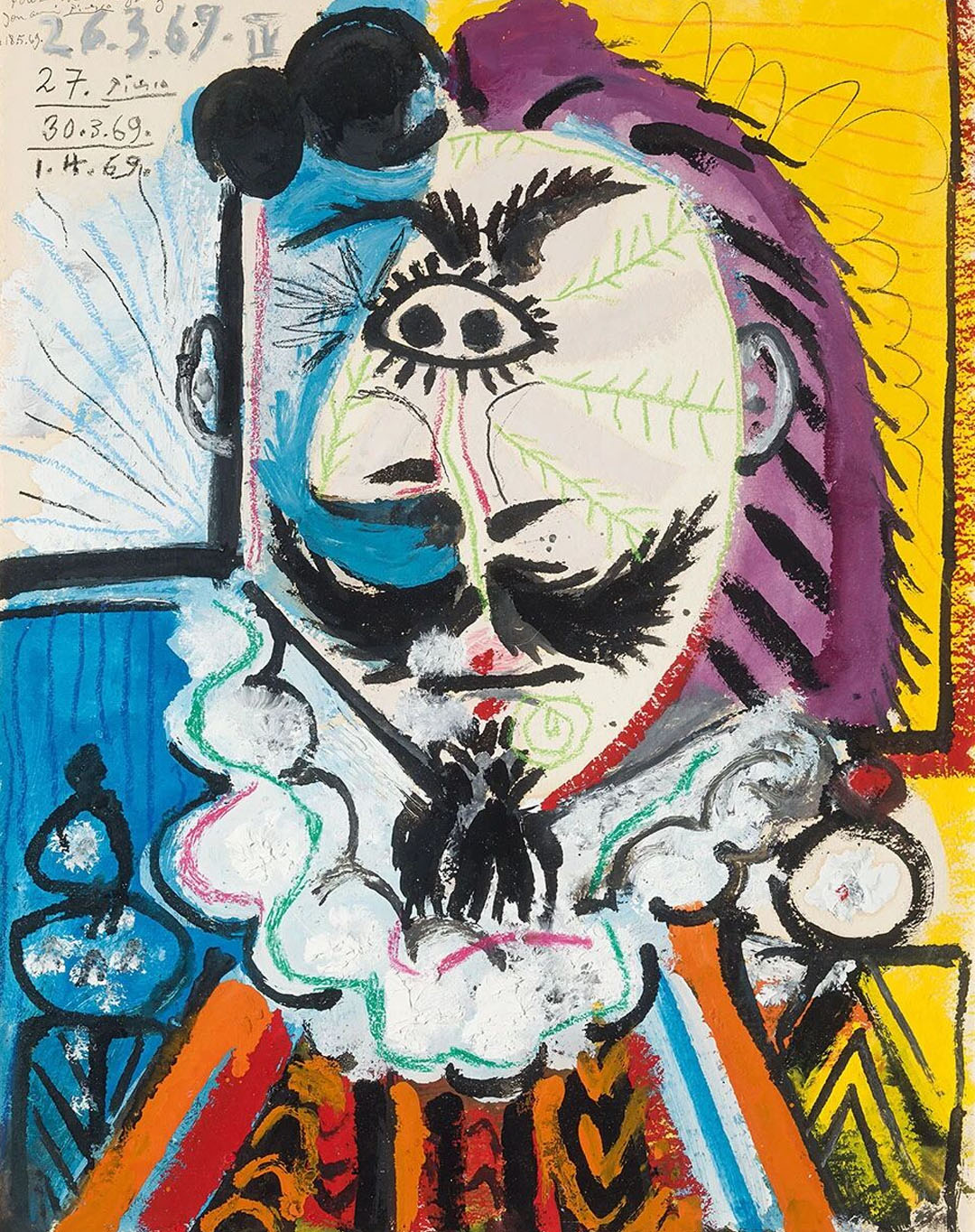

"Tête d’Homme", May 1969, a "fictional portrait" imbued with a sense of stage presence

At this point, “refusal to conclude” ceases to be an abstract slogan and becomes a technical decision. Picasso could have completed the image, polished it, made it resemble a final version—but he chose to stop at the threshold, turning incompletion into a stance.

The Nordic White Cube: Restrained Light, Amplifying an Excess of Brushwork

This sensitivity becomes sharper when moving between Stockholm and Shanghai. Paul Smith’s spatial language in Shanghai—colors, patterns, striped navigational systems—turns viewing into an accessible pathway. By contrast, Stockholm’s cold light and emptiness remove all signposts, allowing the excess of late brushwork to appear without mediation.

Late Picasso is also compelling as a Nordic touring exhibition. In Trondheim, PoMo emphasizes “Code of Painting,” foregrounding method and encoding; in Stockholm, Moderna Museet stresses “A Refusal to Conclude”; in Aalborg, Kunsten highlights long neglect and contemporary reevaluation, framing the period as pioneering and influential. The works themselves are not fixed.

As they travel, they are renamed, reorganized, and retold. What we witness is not only Picasso, but curatorial practice at work.

This points to a distinctly contemporary understanding: exhibitions do not transport meaning—they translate it. Touring is not replication, but repeated re-encoding across contexts. The same works acquire new subtitles, and subtitles change how we see.

Nordic galleries are often imagined as restrained and cool; late Picasso is dense, overheated, excessive. Their encounter does not cancel out but amplifies both. White walls and cold light strip away romanticism. What remains is not the elegance of a genius in old age, but a body thrown into painting—gesture, hesitation, impulse, repetition, loss of control, all laid bare.

The white cube becomes an optical device, sharpening the roughness of late Picasso and preventing “refusal to conclude” from being mistaken for sloppiness. Style alone cannot smooth this over; the paintings insist on being experienced as close-range physical events.

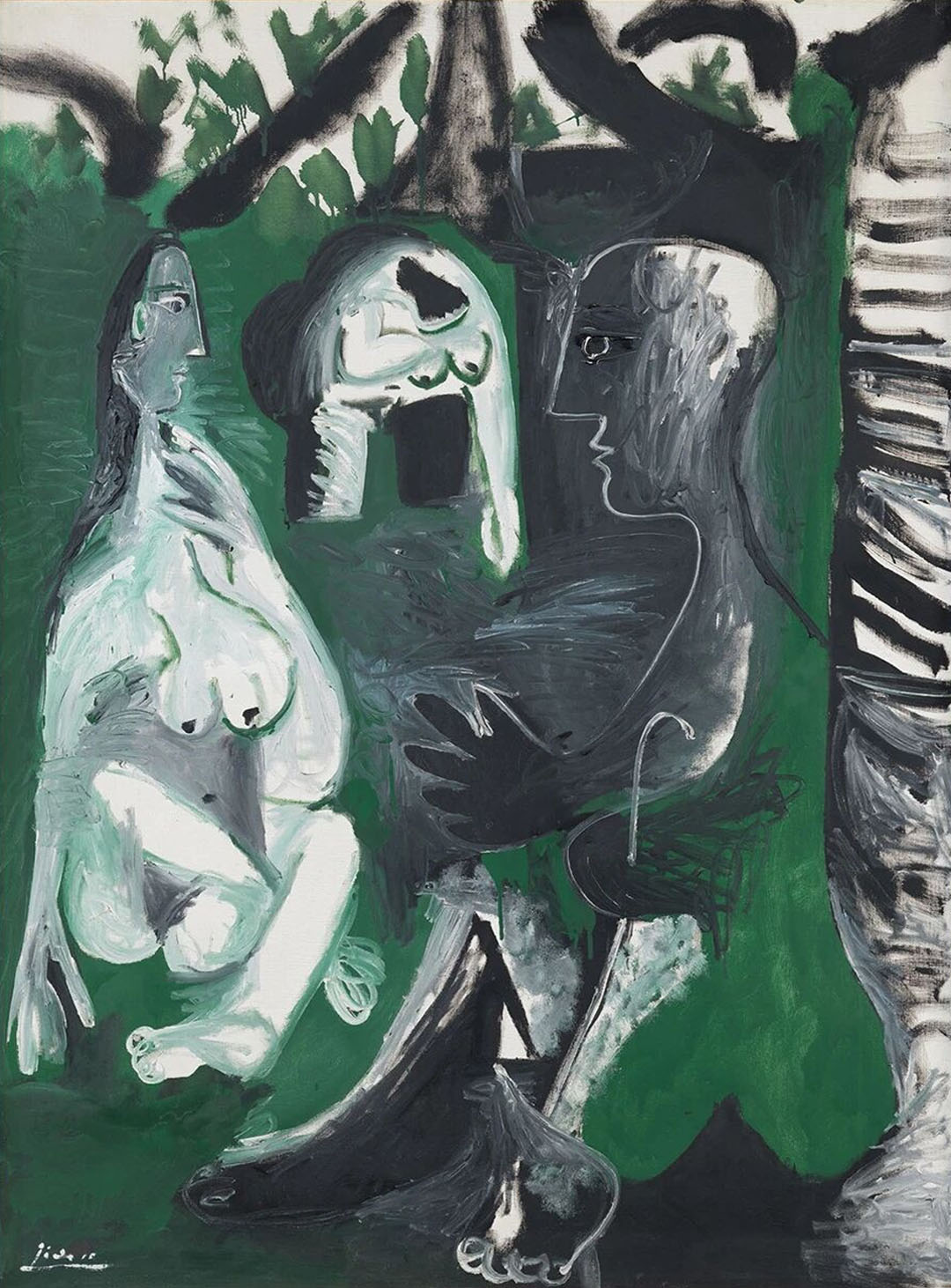

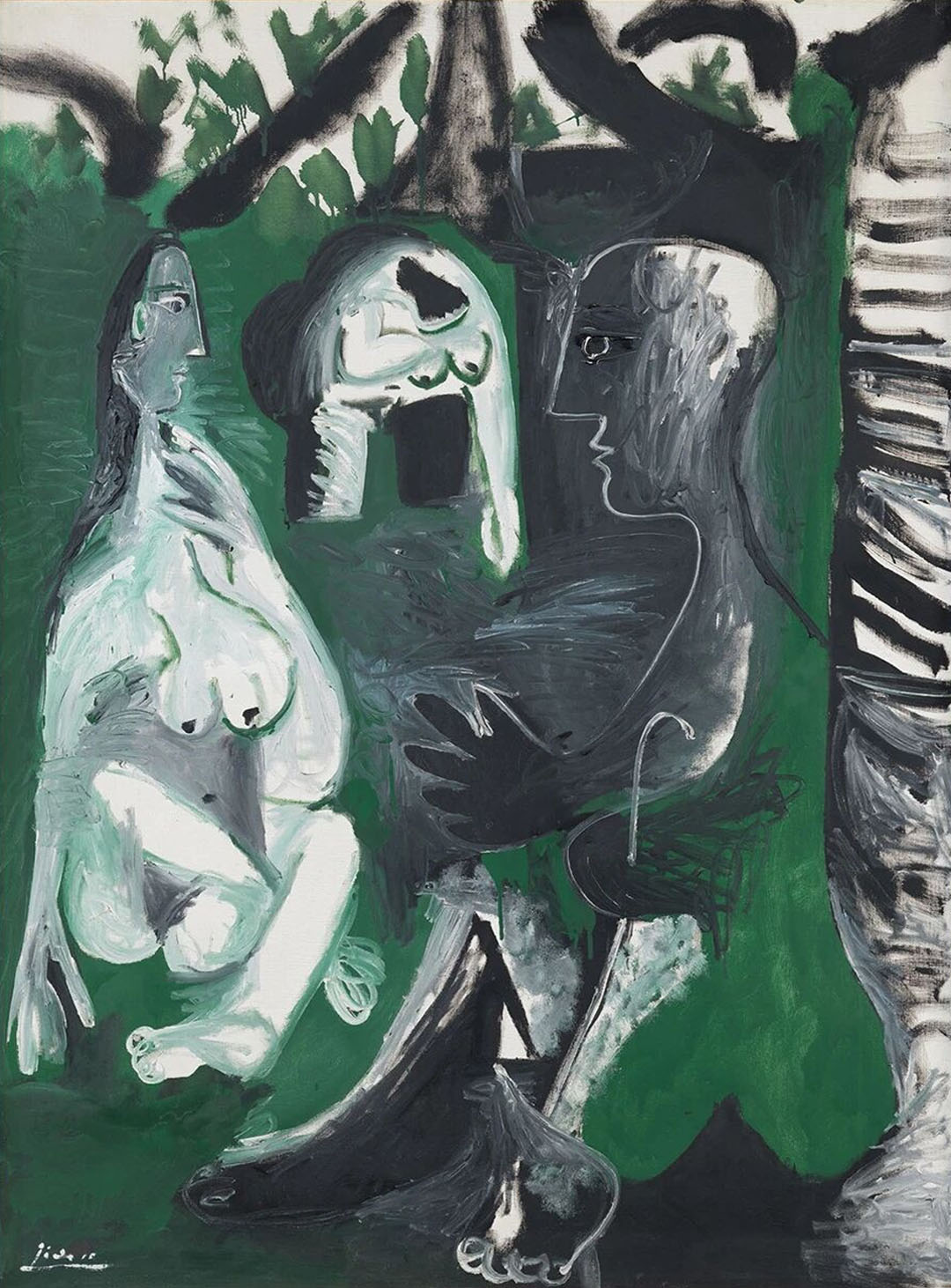

"Breakfast on the Green Grass", Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, July 1961

Under the Shadow of Controversy: How Picasso’s Much-Maligned Late Period Is Being Reread

Any discussion of late Picasso must confront controversy. The period was once criticized as uncontrolled, vulgar, indulgent. Collector and critic Douglas Cooper used extreme language to dismiss these works, while John Berger, in The Success and Failure of Picasso (1965), delivered a sharp critique of Picasso’s late work and its surrounding success narrative.

These debates make Late Picasso a genuinely contemporary project. It does not simply assert that the late work is “also great.” Instead, it reminds us that art-historical judgments shift, scales of viewing change, and even the value system of “finish” can be overturned. Kunsten explicitly notes that this period was long ignored after Picasso’s death, only later to be reassessed and recognized for its influence.

One almost fateful anecdote appears in Moderna Museet’s collection guide: on May 23, 1973—six weeks after Picasso’s death—the exhibition Pablo Picasso 1970–1972. 201 Paintings opened at the Palais des Papes in Avignon. This was the final major exhibition planned by Picasso himself. He personally selected the works, and the catalogue was completed shortly before his death on April 8, 1973.

A man who refused to conclude still arranged how he would be seen.

Leaving the exhibition, we may find that we have not acquired a conclusion about late Picasso. Instead, we gain something more valuable: an ability to treat incompletion as a position rather than a flaw, and to understand touring exhibitions as translation mechanisms through which meaning is generated in motion.

Late Picasso may not please everyone. If early and middle Picasso offered many answers to art history, the late work throws questions back at us: Why are we so hungry for conclusions? Can we accept an image suspended mid-air? Can we treat the unfinished as a stance?

Today, we are thoroughly educated in completion—high definition, retouching, version control, portfolio logic, publishable states. Art increasingly resembles a deliverable product. Late Picasso seems to say: I do not deliver.

The key word of the late period, then, is not freedom, but something sharper: non-cooperation. Non-cooperation with aesthetic order, with elegance, with the demand for a coherent conclusion. This is why the late work was long misread. Measured by standards of completion, it appears regressive; measured by the standard of presence, it becomes frighteningly modern.

The scene of the "Late Picasso" exhibition in Stockholm, 2026 © Moderna Museet

Producer: Tiffany Liu

Editor: Tiffany Liu

Designer: Yuki

Images: Courtesy of Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Pudong Art Museum, Shanghai, the artist, and the internet