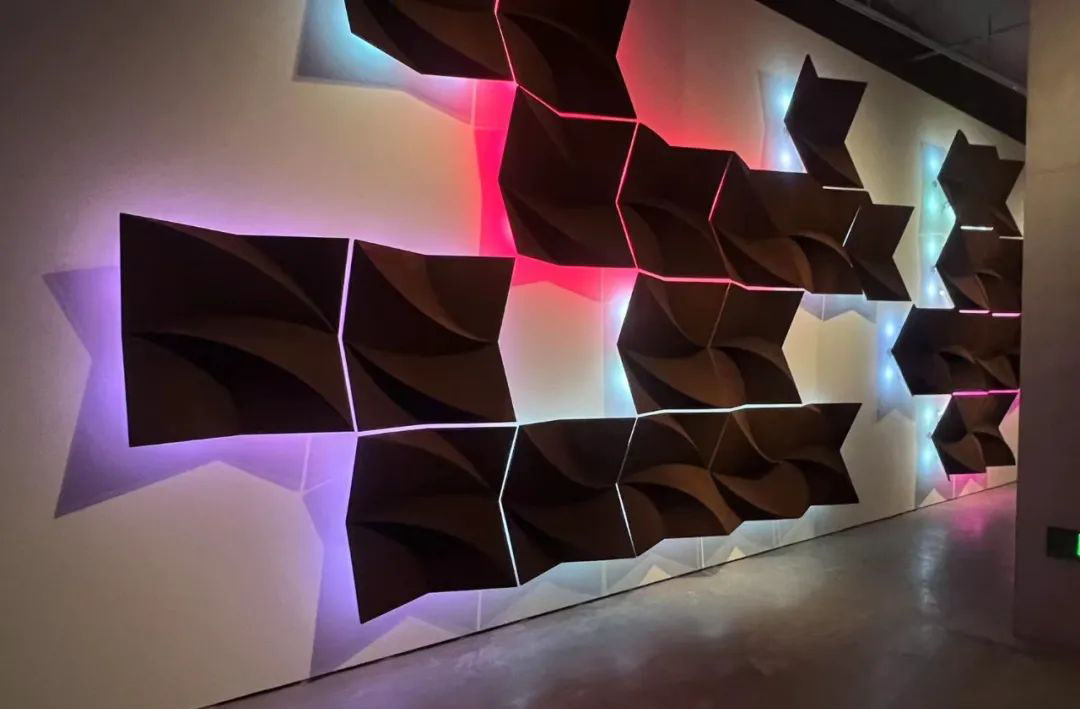

Anselm Reyle, born in 1970 in Tübingen, Germany, is a contemporary artist now living and working in Berlin.Even during his student years, he stood out with his unruly personality and attitude, which have consistently permeated his thinking and artistic practice. Beyond his well-known "visual series" installations featuring materials like silver foil, his 2024 creation—Untitled, his largest neon work to date composed of over 800 neon tubes—became the "year's most Instagrammable moment" at the Xie Zilong Photography Museum in Changsha. This annual blockbuster exhibition earned its English title: Anselm Reyle: Magic Shine Ray 800.

This dazzling installation showcases the artist's decades-long mastery—his bold yet delicate command of light, color, and space. In his hands, the commonplace neon tube transforms into three-dimensional "fluorescent brushstrokes," alternately crisp and aloof or whimsically naive, like graffiti scrawled across an infinite night sky. Encased in silver-mirrored walls, the work refracts flickering urban vignettes, immersing visitors in a fleeting spectacle where the loneliness and brilliance of mortal life are fully revealed.

Recently, the Xie Zilong Photography Museum announced the extension of its 2024 annual exhibition Anselm Reyle: The Glow of Mortal World (launched June 22) through February 9, 2025—a perfect "festive finale" for the Year of the Snake.Hope art enthusiasts will not miss this splendid art feast.

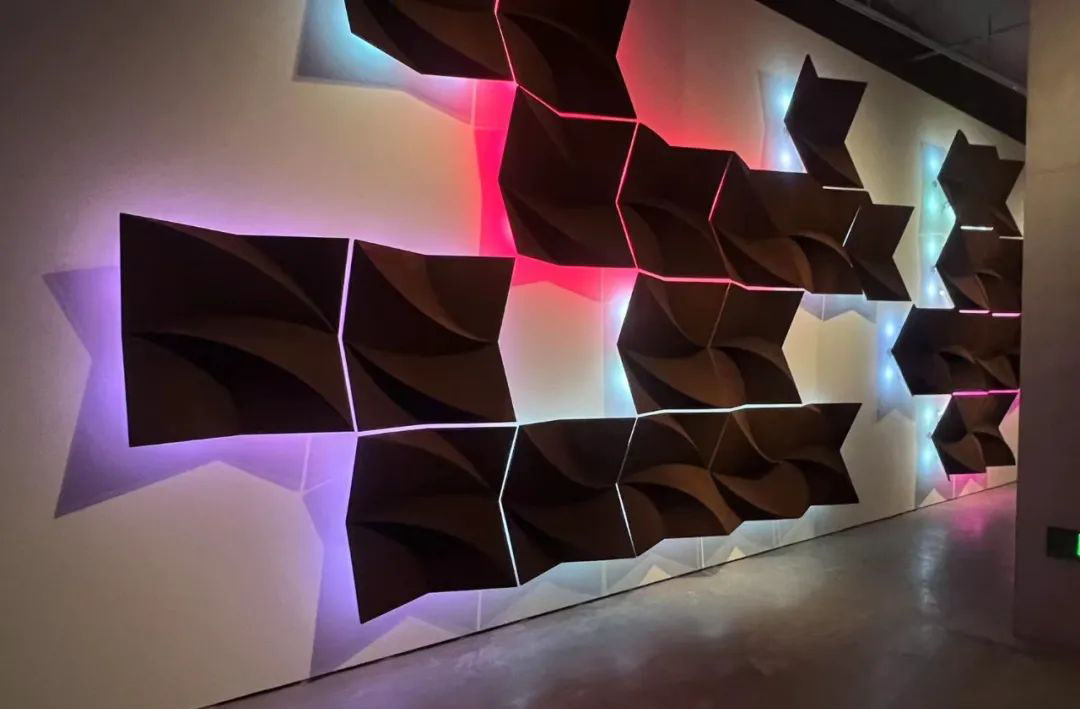

Curated by Xie Jiaqi, Executive Director of the museum, and Dr. Wang Xi, a photography historian, the exhibition offers a panoramic view of Reyle’s pivotal works from the past twelve years: iconic neon installations, silver foil paintings, haystack sculptures, lava-glazed ceramic vases, and recent abstract photography.

Oui Art was invited to conduct an in-depth interview with Anselm Reyle, exploring his formative influences, material experiments, and the profound relationship between his work and the industrial urban era.

When I saw your small-scale Untitled neon series—composed of tubes, acrylic, and wires—incorporating elements like "love," I wanted to discuss composition. My first thought was Russian Constructivist Liubov Popova’s 1921 Spatial Force Construction, where industrial production merged with art to forge a new visual language. Though materials differ, the composition and concept seemed to have a high degree of inheritance. These several works are also a chapter of your large-scale neon works, or a representation of a basic concept. Could you please talk about your compositions and ideas?

This observation is very accurate. This work's composition is indeed influenced by constructivism or Orphism, just as I use the remnants of our industrial and consumer society in my works, I also drew inspiration from modernism. You can also see this in my early stripe paintings. In the history of modern art, there are thousands of such stripe painting works. Through exaggerated and discordant colors, as well as the addition of other materials such as mirrors or foil sheets, my stripe paintings and foil paintings are able to be distinguished from other works.

Let’s discuss your largest neon installation to date. It’s breathtaking in scale yet rich in detail. Did the exhibition title Magic Shine Ray 800 (referencing 800 tubes) come first, or the concept for the massive work?

When I saw the vast space of the museum, I decided to create a large neon installation here. Therefore, a scaffold had to be erected in this space, and then it was covered with silver foil to create the reflection of the neon lights, thus creating an infinite space. When coming up with the title of the work, I would also draw on existing words. I would draw inspiration from songs, B-grade movies or advertising products. For example, "Magic Shine Ray 800" is the name of an innovative bicycle headlight.

At the opening, I noticed many visitors lingering and showing strong desire to take photographs. How do you hope audiences experience your work?

I've observed that in China, taking selfies seems to be more frequent and important than in Europe or America. As long as this doesn't hinder people from experiencing and understanding the art, it doesn't bother me. (I think) it might even create a positive connection.

Neon has become a signature medium for you—a tool to repurpose urban kitsch. Artists like Joseph Kosuth and Bruce Nauman used neon to challenge linguistic norms, while Keith Sonnier expanded painting’s lexicon with it. Who influenced your direction with art? What does neon mean to you, and what do you feel you’ve pioneered?

I believe that throughout the history of modern art, energy, even elements directly derived from the urban environment, have been incorporated into the art. This was especially true in the Pop Art of the 1960s and 1970s, including the fascination with neon lights. Dan Flavin used neon lights in the purest form, giving this material a halo and a sacred quality; some "poor art" (Arte Povera) placed neon light elements on materials such as straw or rusty metal parts, creating a unique energy, and the materials were given life and vitality by the light. I collected the remnants of glass blowing techniques and then created three-dimensional compositions and walk-in light paintings in the space. Later, I also framed these elements on foil paintings, and I discovered that the mixing and reflection of colors on the foil was extremely fascinating.

Your triptych Silver Foil Paintings in pink, blue, and black is visually striking. Why replace traditional pigment with aluminum foil layered under colored acrylic glass? What were you testing?

"Testing" is apt.I’ve used foil for 20 years! Since 2003, I have been continuously developing these images. Now, my foil painting series includes many different types of works. At that time, applying aluminum foil paper to the canvas was indeed an experiment. Using this highly decorative material in abstract paintings felt like it was forbidden in the art world. When I first presented these photos, there were many negative comments. These people were not able to accept the decorative nature of these abstract images, especially the provocative decoration. They might think that decorative elements and practicality are mutually exclusive. I wanted to challenge this notion.

You’ve said, "Many artists explore inward, while I look outward." This contrast is striking. Is it instinctive or intentional?

What I mean is that I get more inspiration from the outside of myself rather than from within. I come across something that interests me and then an idea emerges. However, these things often also attract others, so I don't consider myself a completely outward-oriented person. Rather, I am just one of the majority.

You’ve taught painting at Hamburg Fine Arts University since 2009. During your student days, you once said that you were an "unsubmissive" student. Now, how do you impart art to your students?

I was an average student academically and I resisted all the expectations of the school. That's why I left school early and tried various other things. When I finally came to the art school, I felt like I had found a lifeline, a healing island. This was the first place since kindergarten where I could fit in, and here I found the freedom I needed. I allowed students with similar unconventional experiences to join my class, and during my nearly 20 years as a professor, I noticed that these students often created more intense and more interesting artworks.

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Editor, writer:Tiffany Liu

Designer:Yizhou

The images are partly taken by the author and partly sourced from XPM Museum