The most globally sensational film this year is undoubtedly “The Substance”, written and directed by French female director Coralie Fargeat. In the sluggish post-pandemic film market, this movie leveraged viral marketing through social media snippets to become an unexpected box office hit. It not only dominated European and American theaters upon release but also sparked massive global discourse in a short time. After its online leak, it became the most talked-about film on Chinese social media in October. More than just a viral phenomenon, it is a transitional work that shatters stereotypes about female directors. In November and December, we witnessed more outstanding films by female directors emerging as dark horses, igniting widespread discussion across themes and forms.

01. The Dark Horse Era of Female Directors

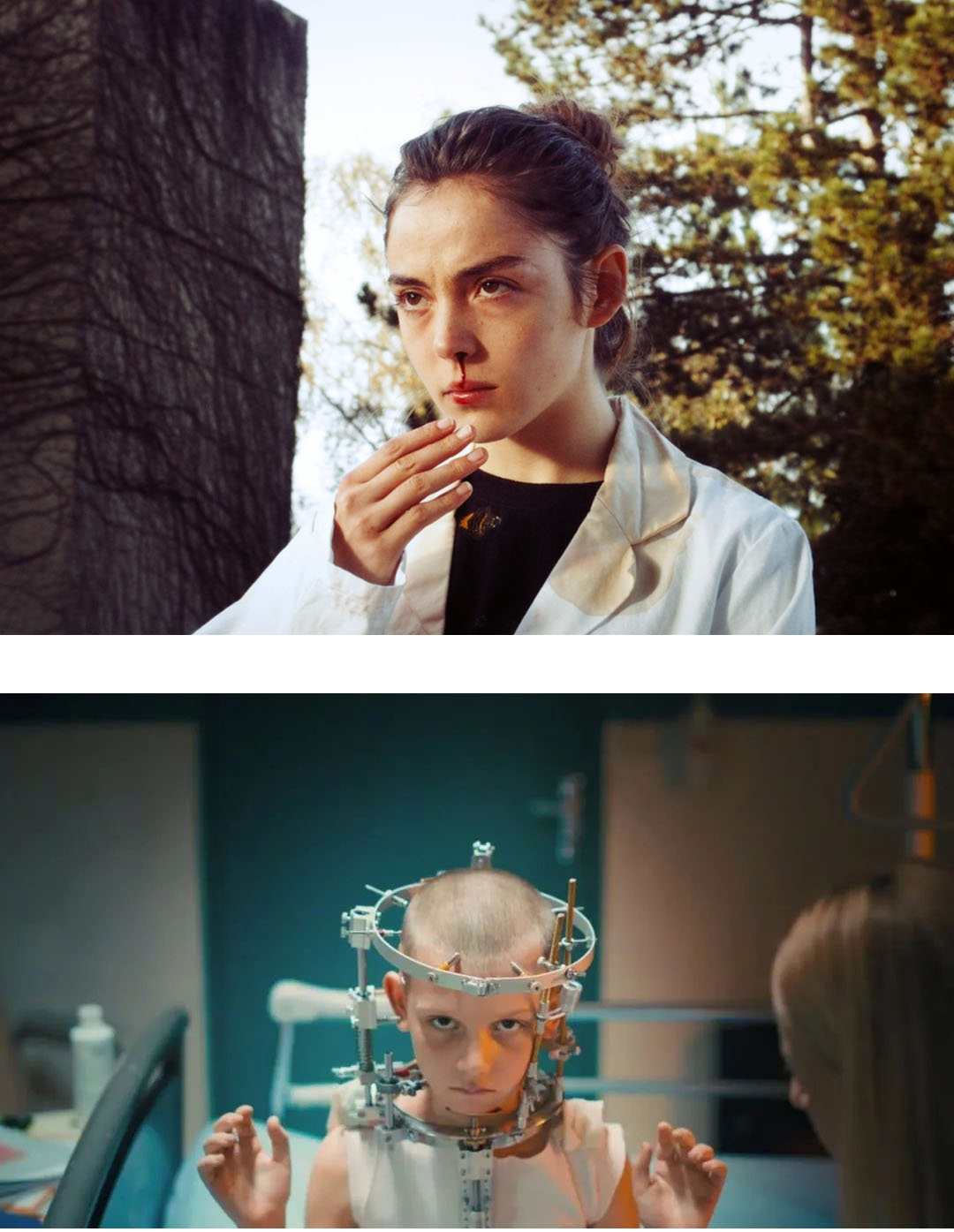

The Substance stars Demi Moore, the iconic actress of the 1980s, as Elizabeth, a once-celebrated Hollywood star unable to accept her aging appearance. Tempted by a black-market drug called "The Substance," she creates a younger, more beautiful version of herself. Initially, the two selves coexist peacefully, but as the allure of fame intensifies, a battle for bodily dominance erupts.

Puffy apple cheeks, plump lips, overfilled foreheads—Hollywood is both a hotspot for appearance anxiety and a goldmine for plastic surgeons. Their scalpels have mass-produced "monsters," with Demi Moore being one of the most infamous victims. Her million-dollar anti-aging transformation is widely known in the U.S. Once a top-tier star who ruled 1990s screens with her beauty, she is now a neglected older actress. Moore’s 40-year career and tumultuous personal life create an intertextual layer that fuels the film’s intrigue.

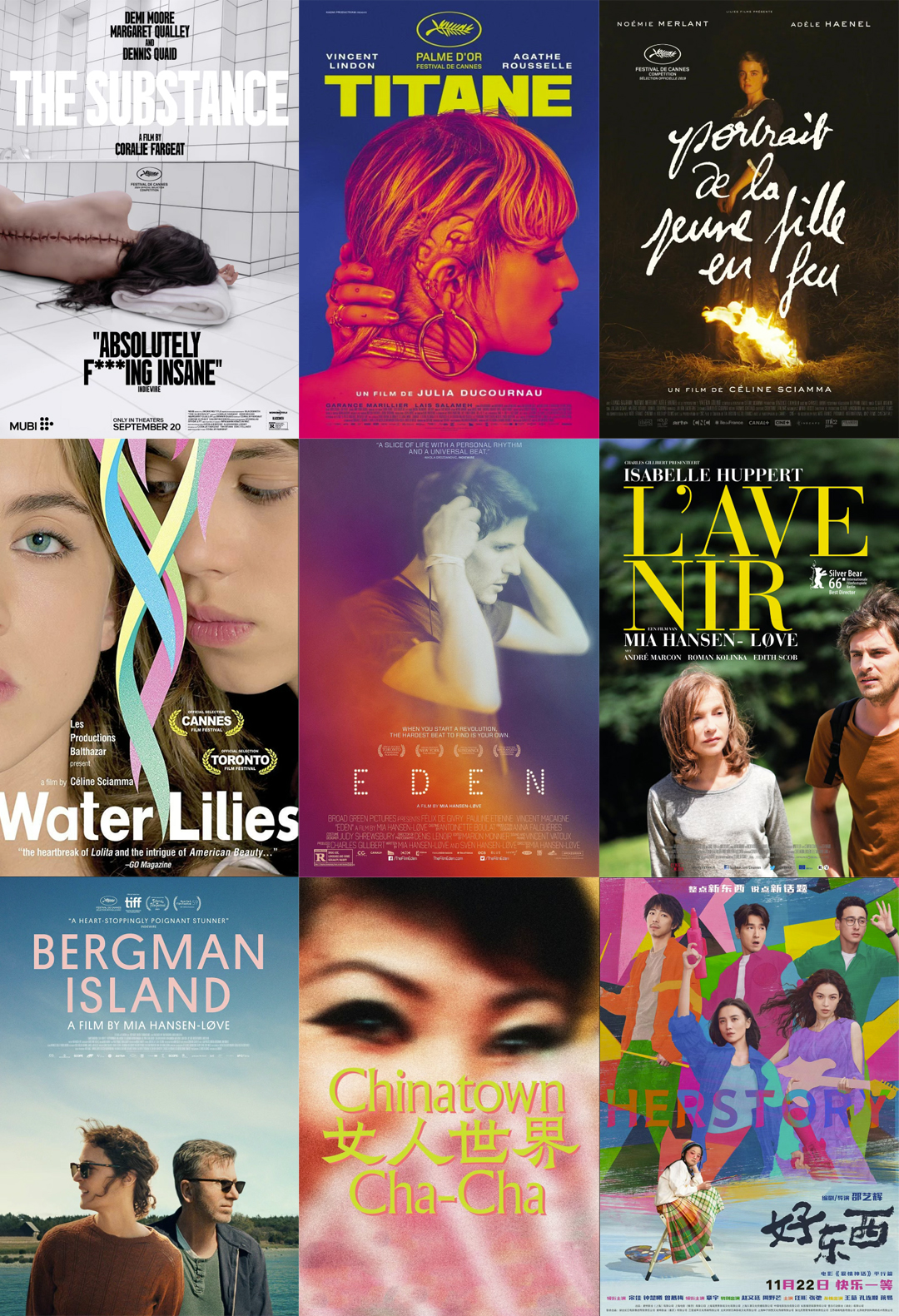

The Substance’s visceral intensity recalls Julia Ducournau’s 2021 Palme d’Or-winning Titane. Ducournau’s second feature after her 2016 debut Raw, Titane pushes body horror to new extremes. Audiences consistently describe it as a deeply unsettling experience.

The film employs extreme close-ups and rapid editing, mimicking the manipulative pace of commercials. Trailers might suggest a conventional thriller, but the actual viewing pins you to your seat with grotesque imagery—hyper-masculine faces devouring shrimp, or the young protagonist’s flawless body parts under the camera’s gaze. None of this delivers pleasure or jump scares; instead, it induces visceral discomfort. Stripped of its "female director" label, the film stands as a pinnacle of neo-female exploitation cinema.

02. Breaking the Genre Trap

We’ve never pigeonholed male directors. Whether it’s Spielberg’s precision, Cameron’s technical bravado, Zhang Yimou’s epic color palettes, or Ang Lee’s tenderness, male narratives have defined our cinematic expectations for a century.

For female directors, we face a paradox: their perspectives are often seen as inherently nuanced,their visual language restrained rather than flamboyant. But must they be confined to delicate, aesthetic imagery?

The director of "The Substance", Coralie Fargeat, was born in 1976, while the director of "Titane", Julia Ducournau, was born in 1983. Although they are 7 years apart in age, they share similar approaches in choosing genre films and visual styles. Through strong visual impact, weak narrative, and weak lyricism, they focus on bloody and violent themes to quickly achieve popularity, thereby breaking our fixed perception of female directors and shattering the genre patterns that have trapped female directors.Female directors have every right to explore all genres, even surpassing men in brutality and audacity.

Yet they risk another trap: their female characters often amplify existing exploitation tropes rather than diversifying them. In the post-#MeToo era, their gender grants them creative leeway and tolerance. When a woman directs female exploitation films, she escapes scrutiny—but whether this advances feminism or invites backlash remains uncertain.

03. The Gentle Female Gaze

Compare this to pre-pandemic hits like Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019 Cannes Best Screenplay) or Mia Hansen-Løve’s Things to Come (2016 Silver Bear for Best Director). These auteurs represent the 2010–2020 benchmark for "female cinema."

Céline Sciamma was born in 1978, while Mia Hansen-Løve was born in 1981. These two directors are of similar age to Coralie Fargeat and Julia Ducournau, and all serve as both directors and screenwriters. However, the former pair's explorations in visual and auditory language differ drastically from the latter's. Without a doubt, Céline Sciamma and Mia Hansen-Løve represent what we conventionally consider the quintessential style of female filmmaking.

As a director from the LGBTQ+ community, Sciamma's works consistently explore themes of female gender and identity fluidity. After graduating from La Fémis, she quickly adapted her graduation script, Water Lilies, into a film. This debut work was selected for the 2007 Cannes Film Festival's "Un Certain Regard" section and received three César Award nominations the following year. Her second film, Tomboy, gained even wider recognition—a coming-of-age story about a teenager grappling with gender confusion, its narrative imbued with tender, profound compassion for gender-fluid individuals that moved audiences deeply. Sciamma's most renowned film is undoubtedly Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019), which not only competed at Cannes that year and won Best Screenplay but also became the first film directed by a woman to win the Queer Palm.

In Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Sciamma employs an exquisitely nuanced approach to tell the story of Marianne, a late-18th-century painter commissioned by a countess to create a wedding portrait of her daughter Héloïse, who has just left a convent. Unwilling to marry, Héloïse refuses to pose, forcing Marianne to paint her in secret. By day, Marianne observes Héloïse; by night, she paints her clandestinely. As their relationship grows increasingly intimate, they share fleeting moments of freedom—both the first and the last—until the portrait is finally completed. The entire narrative extends the ambiguous, drifting emotions between women that Sciamma began exploring in her debut Water Lilies, deepening it into an extraordinarily subtle and moving expression unique to the female perspective.

It is impossible to imagine a male director writing or directing female characters like those in Sciamma's films. This isn't solely due to gender issues or women's circumstances. We must confront the objective reality that, because of biological differences, men and women experience life in fundamentally distinct ways. Men are inherently incapable of writing authentically female roles to the same degree as women—yet our literary and cinematic histories are saturated with female characters penned by male authors. This is both an ironic reality and an infinite creative space for female creators to craft more genuine portrayals of women. Undoubtedly, the ambiguous, heart-stirring relationships between women in Sciamma's films stem from her lived experiences as a woman.

In contrast to Céline Sciamma's several widely acclaimed works, Mia Hansen-Løve maintains a relatively lower profile, with her films bearing a strong autobiographical imprint. Eden (2014), set against the backdrop of Hansen-Løve's youth in the 1990s, follows a group of electronic music enthusiasts as they navigate inevitable interpersonal conflicts between ideals, love, family, and music, along with their bewilderment about the future and the disillusionment that follows faded dreams. Undoubtedly, this film serves as Hansen-Løve's retrospective glance at her own coming-of-age era.

Her 2016 film Things to Come, starring Isabelle Huppert, achieved remarkable success. The minutiae of a philosophy professor couple's late-life divorce in the story mirror the director's personal experiences—her father was a philosophy professor and translator at Sciences Po Paris. Bergman Island (2021), featuring Vicky Krieps and Tim Roth, unmistakably transplants the restrained yet unbalanced dynamic between Hansen-Løve and her husband, the renowned French filmmaker Olivier Assayas, onto the screen. Her most recent work, One Fine Morning (2022), starring Léa Seydoux, depicts the protagonist Sandra juggling care for her young daughter and ailing father—a narrative clearly drawn from the director's own experience of losing her father in 2020.

Across these four recent films, we witness the director's personal life experiences permeating every role, portraying life's unpredictability and mundanity with extraordinary lightness and liveliness. Her films often forgo intense plot conflicts, focusing instead on familial ethics, yet they exemplify the quintessential French "cinema of everyday life." By magnifying life's smallest fragments, she effortlessly draws audiences into her characters' plights, allowing us to viscerally empathize with their all-too-familiar uncertainties and dilemmas.

04. Chinese Screens Bloom with Female Voices

Two critically acclaimed films dominated this year's autumn season: Yang Yuanyuan's Chinatown Cha-Cha and Shao Yihui's Her Story. These works by Chinese female directors present us with diverse female characters from all walks of life.Yang Yuanyuan's Chinatown Cha-Cha focuses on a dance troupe composed of Asian women over 70 years old. Coming from varied professions and mostly divorced or widowed, they gather to eat, drink, travel together, and embark on a performance tour that takes them from the United States and Cuba to eventually arrive in China. Through the elderly dancers' recollections, the film weaves together the history of Chinese-American dancers from San Francisco Chinatown's golden era. As Yang Yuanyuan states, "I reject grand narratives, believing history is composed of the intertwined migrations of overlooked individuals."The 92-year-old Coby, who features prominently in the film, was the last owner of San Francisco's "Forbidden City Nightclub". Her presence undeniably captivates audiences - though her aged body moves heavily, on stage she remains as light as a gorgeous butterfly slowly unfurling its wings in dance. Through her wrinkled skin, we glimpse the radiant flow of time folded within.

The overseas Chinese female group undoubtedly constitutes an marginalized group within the female population. Coby, born in 1926 in Ohio, USA, is a typical representative of this group. As a second-generation immigrant in the United States, she knows almost no Chinese except for her name Yu Jinqiao and the name of her father's hometown. She has always loved tap dancing and jazz music and has gradually become the most famous dancer in San Francisco nightclubs, being called "the Chinese Gypsy Rose". In that era, the dancers in nightclubs were still in a situation of being stared at by men and being exploited, and the status of Chinese people was far lower than that of white people in the American society. Chinese female dancers inevitably found themselves in a situation of being exoticized and doubly marginalized. The overseas Chinese female group, whether in the past or at present, remains an unappreciated group by society. Although the popular movies "Crazy Rich Asians" or "Everything Everywhere All at Once" a few years ago were about Asian women, they more or less presented the overseas Asian female group from a curious perspective rather than a realistic and objective one. Yang Yuanyuan's "Chinatown Cha-Cha" undoubtedly precisely focuses on this group of historical carriers that is about to disappear in time, bringing the 20th-century overseas Chinese female group back to the screen and permanently leaving these lively women in the images, being vividly remembered forever. In the ending of the film, the image of Coby dancing the last dance will also continue to move those who watch the film as the light and shadow flow.

Shao Yihui's Her Story undoubtedly emerged as the most delightful surprise in year-end theatrical releases. With its perfectly paced 123-minute runtime, the film guides audiences through life's vicissitudes via its female-led narrative. As a light comedy, Shao introduces us to Wang Tiemei and Ye - two strikingly different yet thoroughly modern urban women - alongside the utterly heartwarming child character Wang Moli. Rarely does Chinese cinema present female figures like Wang Tiemei: efficient, free-spirited, and refreshingly free from emotional baggage. Forty years into China's reform and opening-up, just as contemporary female characters were regressing to feudal-era stereotypes, Shao Yihui has forcefully dragged them back into modernity. This autumn season finally gives us female protagonists truly synchronized with our times. The film's rejection of "feminine rivalry" in favor of celebrating sisterhood offers a poignant counterpoint to our era of involution and resignation.

Last summer's global phenomenon Barbie detonated like a pink sugar-coated nuclear bomb, not only igniting worldwide feminist discourse but propelling female directors beyond art-house confines into mainstream commercial cinema. From this year's The Substance (a female-directed, blood-soaked exploitation film) to Chinatown Cha-Cha and Her Story, we witness female filmmakers flourishing across world cinema. Their audiences have long transcended gender boundaries to embrace global viewership.Whether through ethical complexity or visual-aural impact, these directors expand cinema's imaginative possibilities while creating vividly three-dimensional characters. In their mature audiovisual storytelling, we glimpse life's boundless potential - and by extension, cinema's too.

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Editor:Tiffany Liu

Writer:Dany Zheng

Designer:Yizhou

Image organization:Yoko Liu