I refrain from using "plagiarism" to describe this phenomenon, as the most blatant plagiarism occurs between works of the same genre: consider the paintings of Artists Ye and Xu, which are near carbon copies of others' works—an unmistakable case of plagiarism. The controversy surrounding Artist Zhang’s “Xiaohongshu appropriation," however, extends beyond legal copyright issues. Even if consent was obtained from the subjects in the images, it doesn’t mitigate the public’s stunned disbelief upon realizing, "So this is how 'artistic creation' works now?"

What underlies this shock? While insiders are well aware of contemporary art’s declining spiritual rigor, the brazen exposure of art’s fall from elitism—its reliance on stealing from mass trends—lays bare an uncomfortable truth. Ready-made images, like pre-cooked meals, are tweaked and served. What kind of feeling does it give ? Everyone’s an artist now—except the professionals.

Why "Xiaohongshu Appropriation Art" deserves critique?First, we must clarify why Artist Zhang’s approach doesn’t qualify as "found object" or "appropriation" art. Found objects became artistic expressions as a natural evolution of conceptual art, symbolizing the deconstruction of traditional academic systems and embodying contemporary art’s core tenet: independent spirit. This independence isn’t just about Duchamp’s urinal upending artistic norms—it’s about transcending discipline to uncover new layers, possibilities, and critiques in the mundane. Even the “King of Kitsch”, Jeff Koons, in his controversial appropriations of ads and consumer goods, retains a whiff of critique: our lives are as abundant as advertisements, yet as hollow; as cheerful as cheap trinkets, yet as terrifyingly empty.

Yet in Zhang’s “Xiaohongshu Appropriation",did the essential "new meaning" of appropriation come into being? Before the scandal, her works sold briskly, riding on their obvious aesthetic appeal: narrative ambiance requiring no explanation, petit-bourgeois filter tones, and decorativeness tailor-made for entry-level "artsy" interiors.

All this caters to superficial sensory pleasure. As Mark Rothko noted: "Our society has substituted taste for truth in art. We prioritize pleasure over responsibility, changing tastes as frequently as hats or shoes." Indeed, art now occupies the same space as consumer goods and entertainment. In an era where cheap aesthetics are effortlessly accessible, even "artists"—once synonymous with creativity—have lost originality. When narcissistic aesthetics can’t even originate, we’re left recycling secondhand imagery into third or fourth hand copies. Screen-age creators must confront the pervasive "secondhandness" and "indirectness" in contemporary works and make conscious choices.

Disconnected from Reality: The Withering of Aura

Andy Warhol was a master of reproduction and also a master of appropriation. His brilliance lay in his utilization of the harm that inanimate objects (industrial replication) inevitably inflict upon sentient objects (life), thereby ingeniously concealing and exploiting the cold criticism hidden within. Take that vivid Marilyn Monroe portrait for example. Every time the colors are changed and replicated, it is a concealment and exploitation of Monroe as a living being. To describe this with a sentence from Benjamin's important article “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” published in 1936: "The withering of the aura."

The replication age feeds illusory gratification—instant but never fulfilling. What we have obtained is merely a “withering of the aura” replica: “Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” This "unique existence" isn’t ephemeral; it’s the authenticity that, rooted in life’s rhythm (not mechanical reproduction), perpetuates itself infinitely through successive "here and nows."

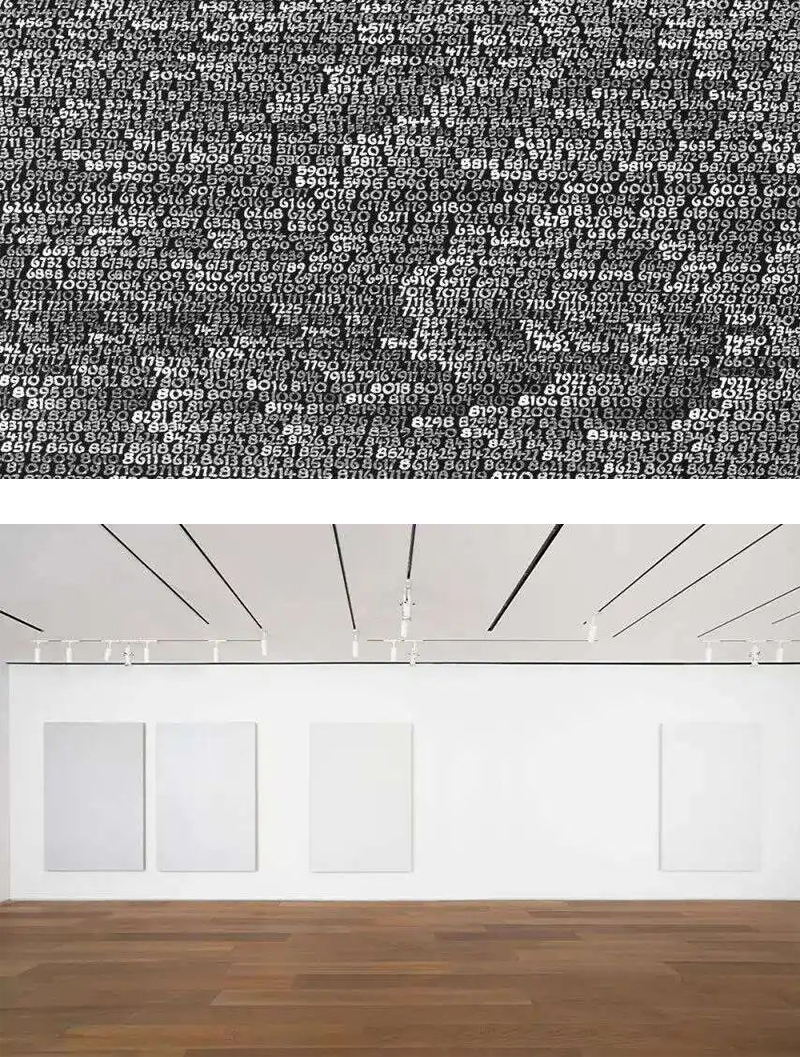

Roman Opalka’s practice epitomized this: from 1965 until his death in 2011, he painted numbers sequentially from "1" toward infinity. The black canvas gradually whitened until the numbers vanished into blankness. His labor wasn’t replication (which diminishes sovereignty) but repetition (which asserts it). Each stroke reaffirmed his will; the final "empty" canvas radiated his lifelong defiance of oblivion.

Unfortunately, nowadays we increasingly doubt the simple will, but are more and more obsessed with the sentimental theater - because the theater has already set everything, you just need to immediately immerse yourself in the pre-prepared plot and atmosphere, and you can enjoy the pre-prepared aesthetic, ready to use at any time, seeing and getting exactly what you want. This is why the dramatic-style paintings are so popular nowadays. However, what you obtain is a false second-hand thing disconnected from reality, an imitation of emotions. Falseness cannot nourish truth; falseness will only generate more falseness. Just like eating too much stimulating pre-prepared food, you will instead be unable to adapt to the naturalness of real food. Under the sensory limitations that have become accustomed to the routine aesthetic, you have self-censored the possibility of exploring more truths.

The "Homo Faber" Who Manufactures Without Creating

If we don’t stop producing "secondhand objects," human creativity will never surpass AI’s.

Why does advanced technology weaken creativity? Convenience breeds sluggishness. Creators rely on tools for everything, but even the smartest AI can’t produce a Duchamp while excelling at Rembrandt replicas. Tools easily copy objective "representation" but fail at subjective "expression"—the truth of the soul. Those dependent on tools forget how to touch reality’s infinitude.

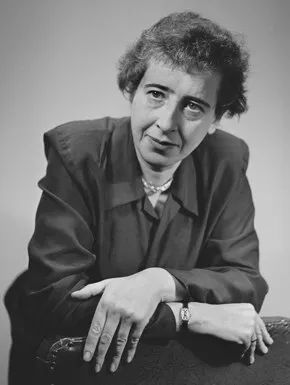

As early as in Hannah Arendt's 1958 work "The Human Condition", she already pointed out the greatest difference between AI and human creation: it is the distinction between "making" and "acting", "work" and "deeds". Arendt referred to this kind of existence that can only "making" and "work" as "homo faber" - "To homo faber, the world appears as a vast storehouse of materials, a kind of fabric to be cut up and refashioned according to his purposes." AI is the "homo faber" created in this era, and the emergence of AI has also inversely promoted humans to become more lazy "homo faber" . Everything can be used for something, and it is best to omit the process and increase production capacity. All aim to complete tasks faster. Therefore, the seemingly intelligent and all-powerful "homo faber" actually deprives everything of its inherent independent value. All things have fallen into the role of means to achieve the goal, and the "homo faber" itself has become a tool in the utilitarian world.

A life without a process is false, and art without a process is empty. Re-entering the "flow", returning to the clumsy, honest, and process that brings a sense of real existence, that is the solace and reward that creators should most deserve beyond the pursuit of utilitarian goals.

Authenticity: The Only Lifeline in the Screen Age

Surrounded by screens and drowning in cheap aesthetics, how does creativity survive? Only through authenticity—art’s sole vital lifeline.

This authenticity lies in the honesty towards the present reality. Why do many of Tuymans pictures, which come from his screen memories as the first-generation TV child, do not give a false preconceived impression? Because it is a kind of detachment with genuine emotions, and a hint of compassion in the humanistic examination, which is an honest expression of the artist's inner feelings, rather than reinforcing a false atmosphere through pre-designed picture scenarios.

This authenticity lies in the courageous display of imperfection. Benjamin proposed a kind of "positive barbarism”, suggesting that in extreme circumstances, civilization can sacrifice elegance and continue its existence in a crude form. Just like the "Fauvism" movement, with its bold and terrifying colors and vitality, it enabled artists in the process of industrial urbanization to retain their most passionate emotions, and did not consider themselves as the controllers of cold tools as a source of pride.

This authenticity lies in returning to the natural laws of life. Only when we are willing to let go of utilitarian goals and no longer consider achieving tasks as the ultimate goal, can we possibly regain our sense of rhythm and re-enter the flow of natural generation. Although this is very difficult in the current era where art is highly commercialized, ignoring the process of replication is equivalent to committing suicide for the sake of quenching thirst for the creators.

As Rothko declared: "The conscience of art is its authenticity."

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Editor:Tiffany Liu

Writer:徐薇

Designer:Nina

The image is sourced from the internet and provided by the author