For Chinese artists who have reached a certain stage of maturity, a latent genetic instinct often awakens—a craving for the “grand.”

Grand spectacles, massive productions, and colossal scales seem to signal career success—after all, realizing such visions demands equally vast resources and capital. Beyond the tangible satisfaction of material achievement, a spiritual legacy lingers in the blood of Chinese artists, inherited from Xu Beihong’s tradition of large-scale historical themes also returns to haunt contemporary artists: a historical sense of duty to "convey morality through art," an artistic consciousness of merging personal destiny with the tides of the times, a high-dimensional perspective for navigating worldly confusion. While this aligns seamlessly with the traditional responsibility of Chinese literati, it also clearly clashes with the core spirit of contemporary art. The collectivist and didactic undertones of that lineage jar with the individualistic and critical ethos of today’s art world. This is not just a friction between the individual and the collective, but also a question of how artists transcend modernist methods to truly enter the contemporary discourse—how to expand externally while simultaneously cultivating inner density. These are thoughts sparked by my experience of Yin Xiuzhen’s solo exhibition Piercing the Sky.

For a leading Chinese artist like Yin, staging a major show at an institution like Shanghai’s Power Station of Art (PSA) at the peak of her career is pivotal. Here, she presents her most current work in massive form—yet this very scale lays bare artistic vulnerabilities, impossible to hide. Through Yin’s case, we glimpse the real challenges facing today’s Chinese "successful" artists.

Size isn’t merely a visible disparity in physical form; it’s the dialectic between macro and micro, abstract and concrete, distance and immediacy. Before monumentality seduces an artist, true creation begins with pinpointing one’s own "smallness"—the precise expression of subtle sensations as a foundational path. Yin once excelled at this: her early works throbbed with acute sensitivity to lived trauma. In the 1990s, she collected furniture and dust from demolition sites, silently arranging them into Ruins; she embedded worn shoes in cement to form relic-like Road; cloth shoes fused with photographs in Yin Xiuzhen echoed this elegiac tone. These works fixated on obscured, erased memories—not as nostalgia, but as a visceral response to the era’s breakneck development. While others raced forward, Yin’s "bodily awareness" sensed not renewal, but a hollowing-out. Thus, she anchored lives in cement, made them tangible through shoe soles.

Whether resisting power’s erasures or offering a second skin to trauma, Yin’s genius lay in sensing "what life endures." Early on, this sensitivity carved narrow gateways for expression. Through humble and simple methods—casting, sewing, collecting—her works forced life’s struggling vitality through narrow passageways. The sincerity tinged with pain was deeply moving. Yet thirty years later, in PSA’s cavernous space, those early constraints vanish. Faced with the lure of filling vastness, sensitivity shifts from an asset to an obstacle. Let’s return to Piercing the Sky to see what unfolds when "scaling up" becomes the challenge.

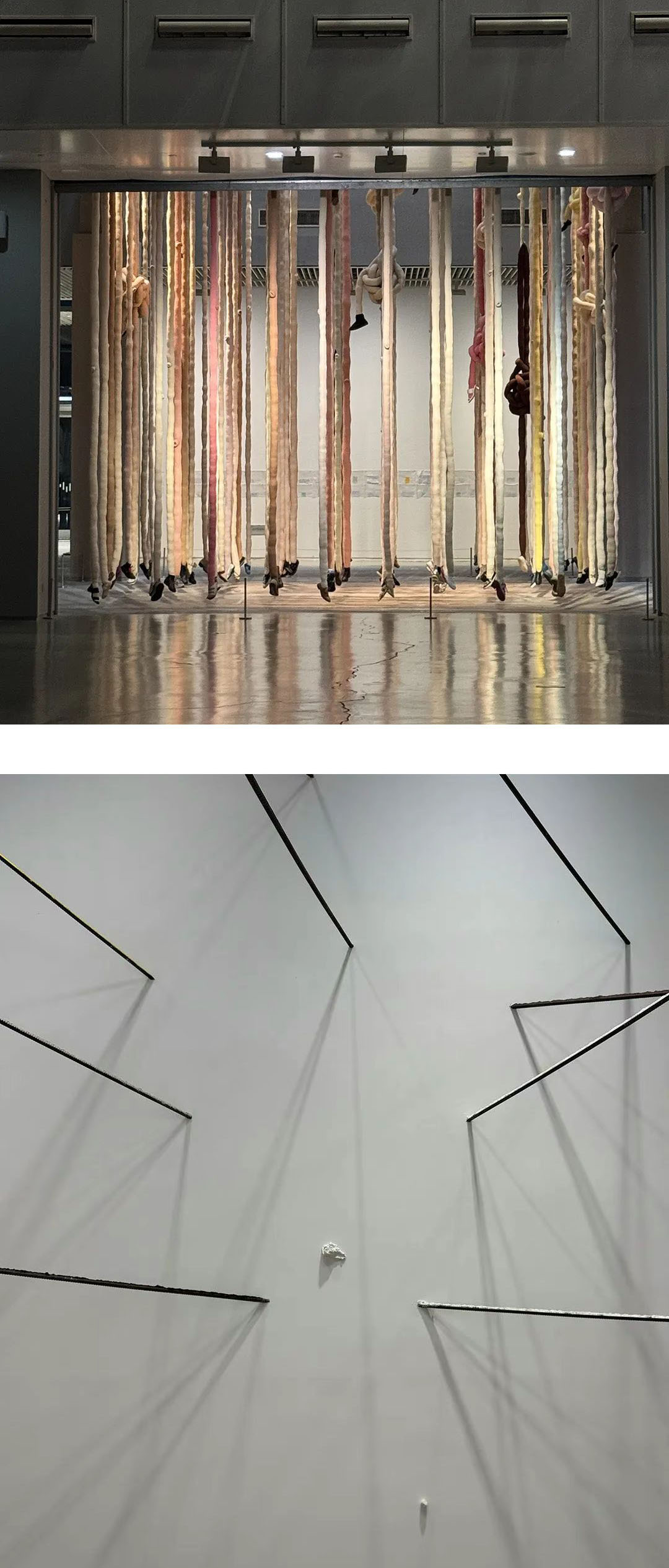

There are two strategies to achieve “grandness”: the singularly monumental (Piercing the Sky being the most eye-catching), and the aggregation of many parts—Action and Reflection and 1080 Breaths at PSA Shanghai being examples. Chinese artists instinctively handle "multitude"—think Xu Bing carving 4,000 “square word calligraphy”, Qiu Zhijie rewriting Preface of the Orchid Pavilion into oblivion, or Li Xianting defining "Beads and Brushstrokes" as endless, prayer-bead-like repetition. This "multitude" isn’t about outcome but process—a life-driven compulsion: the unstoppable repetition of redemption. Only through repetition can emotions settle, confessions flow, strength release.

Please note: repetition is not duplication. Duplication entails cold replication; repetition involves continuous action. Re-examining Action and Reflection and 1080 Breaths at PSA Shanghai, we must ask: Is this mass-producing an existing IP, or repeating an ongoing, authentic act? These installations carry strong narrative and contextual dimensions—Action and Reflection’s prototype appeared in 1996’s Cement Shoes, where eviction-facing Yin filled shoes with cement, lining them toe-down to manifest weight after life’s abrupt cancellation—a silent resistance.

"Multitude" as resistance is necessary; as truth-telling, too. But when artists, like directors, prioritize formal grandeur over connective "smallness," reducing reality to plot points rather than lived wounds—no matter how many actors or how polished their makeup—can the performance still move us?

Pursuing "grandness” often lures artists into theatricality.

Walking through the exhibition feels like traversing stages: Flying Machine, Piercing the Sky, and Sky Patch form a triptych of agrarian-to-modern alienation and ambition; Tower of Sound visualizes audio waves; Tunnel compresses daily survival; Saliva suspends online vitriol as symbol... These recent works share a method: stitching metaphors into "meaning theaters." Plots pivot between conflict, calm, and mystery. Yet for all its dazzle, this theater remains trapped in modernity’s permutations, never reaching contemporaneity’s core. Why?

Even brilliant metaphors aren’t summaries. Metaphors are replaceable surface; summaries are evolutionary acts probing essence. This distinction—"surface variation" vs. "essence excavation"—separates modernity from contemporaneity. As Arthur Danto describes modernity in his renowned essay "Modern, Postmodern, and Contemporary":

"Modernity is characterized by using a discipline-specific method to criticize the discipline itself, rather than to subvert it.

" Conversely, the task of contemporaneity is precisely subversion, but the purpose of this subversion is to penetrate all constraints, embodying "the intention of connecting art directly to people's lives."

This also distinguishes performance art (unframed summaries of lived experience) from performing art (framed representations). As Michael Fried critiques the theatricality of art in Art and Objecthood, he asserts that "theater is now the negation of art", a condition encompassing its orchestration of the viewer's "situation" and its pursuit of interdisciplinary "synthesis". Instead, true art must strive for presentness:

"Presentness is grace. At its best, a single and instantaneous moment suffices: one is struck by it, convinced by its depth and wholeness, persuaded forever... I want to say that it is by virtue of their presentness and instantaneousness that they defeat theater."

Still, artists find it hard to resist the allure of theatricality—not just because it’s easier than distillation, but because it’s emotionally impactful. Like Wagner’s vision of Gesamtkunstwerk, totalized sensory art.. But Alain Badiou cautions against the illusion that combining all forms enhances power,“we must create a new art, which certainly includes new forms, but should not fantasize about the totalization of all sensible forms," he said. The triptych Flying Machine, Piercing the Sky, and Sky Patch epitomizes this totalizing. Flying Machine (2008 Shanghai Biennale) originally cloaked industrial coldness with fabric—a agrarian caress. Here, it’s reduced to prop, its material poetics buried under role-playing.

Notably, prior PSA solo shows by Liang Shaoji and Hu Xiangcheng also leaned theatrical. I don’t doubt the artists’ critical sincerity, but ignoring this traps art in "scene games" and "visual puzzles." With infinite narratives to spin, returning to the chaotic origin—seemingly limiting—is the real test.

Final question: Can an Artist Truly Shape the “Grand”?

Not all "grandness” aims for results—only when necessity demands it. There are several typical examples: First, shaping life itself in grand actions. For instance, in the final work of Marina Abramović and Ulay, "The Lovers: The Great Wall Walk", the long and arduous trek along the Great Wall was regarded as a ritual to advance the development of life. The core of the Christo couple's wrapping behavior is ambition. Whether it is the Parliament building symbolizing political power or the canyon coast representing the power of nature, the more grand the object wrapped, the more it highlights the ambition of the will to live. Second, explore the hidden attributes of the "grandness" itself. As Richard Serra spent his entire life studying the gravity of steel, he sketched the elegant boundaries of energy movement within the immense weight. The third and most challenging necessity arises from the correspondence between "the infinitesimal with no interior" (其小无内) and "the boundless with no exterior" (其大无外). This is the natural coexistence of the hidden and the grand, and it is the infinite pattern that naturally emerges when an individual's depth and sensitivity are pushed to the limit. And this is, in my opinion, the most suitable path for Yin Xiuzhen to achieve "grandness".

Yin’s sensitivity is undeniable—a gift for shared empathy. A decade ago, Weeping Vessel moved me deeply. Such empathy bridges trauma universally. But sensitivity’s flaw is diffuseness; it reacts to everything. Yin’s works constantly respond: Screen Wall of Gaze uses microscopic eye reflections to refract reality; Unknown and Myth of Deer dissect technology’s grip on life. Yet identifying issues is just the start. If sensitivity merely discovers and cleverly metaphors, the distilled spectacle may intrigue but not stir—becoming cleverness, not lived truth.

Stability for sensitivity can’t come from perpetuating surfaces (self-replication). Dress Box (1996) brimmed with simple life; its spin-off Portable Cities retained the form but lost visceral power in craftiness. Similarly, Tower of Sound’s nylon membranes awe technically but leave senses cold.

Extending artistic elements is grueling. Unnecessary surface iterations deplete value; meaningful continuity explores constraints—using, questioning, even returning to an element’s intrinsic infinity. This demands relentless sensitivity to truth. In an era of novelty, art’s task isn’t invention. Only by rooting in origins, refining amid temptations, can artists re-enter the "inward infinite" and construct a "boundless" spiritual home.

We’ve lived through ambitious times. Post-striving inertia still drives us to fill grand molds—until the hollowness of falsity collapses under its own weight. Perhaps this is the pivotal turn: flashy shells no longer suffice. It’s time to return—to beginnings, to the present—before our sensitivity to truth numbs completely.

Producer:Tiffany Liu

Editor:Tiffany Liu

Writer:徐薇

Designer:Nina

Photographer:Claire

Some images are sourced from the internet

The images and texts are not authorized by Oui Art and shall not be used without authorization